This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "How the Mighty Fall" by Jim Collins. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How do formidable companies lose their footing and fall into irrelevance? What are the most insightful How the Mighty Fall quotes?

In his book How the Mighty Fall, Jim Collins discusses the five phases that lead to a company’s decline. He also breaks down how to resuscitate a faltering company.

Keep reading for the best How the Mighty Fall quotes to get the main ideas.

How the Mighty Fall Quotes

How do formidable companies lose their footing and fall into irrelevance—or even cease to exist? And how can other companies avoid the same fate? Jim Collins seeks to answer these questions in How the Mighty Fall. Backed by years of research into once-mighty companies, Collins contends there are five phases leading to a company’s downfall: overconfidence, overreaching, ignoring the signs, overcorrecting, and surrendering.

While the book is a warning to companies that have grown complacent, it also gives hope to those in the throes of decline. Collins says that by staying vigilant of the threat of failure, you can rechart your course, keep pushing forward, and ensure your company’s survival.

Below are the top three How the Mighty Fall quotes with context.

“I’ve come to see institutional decline like a staged disease: harder to detect but easier to cure in the early stages, easier to detect but harder to cure in the later stages. An institution can look strong on the outside but already be sick on the inside.”

Collins analyzes companies’ performance through the lens of failure rather than success, arguing that understanding failure helps companies avoid it. To determine the causes of decline, he takes pairs of companies in the same industry, analyzes what the failed companies did differently from the successful ones, and determines what the failed companies had in common.

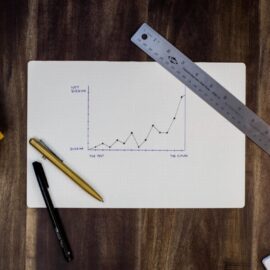

Collins writes that companies don’t fail overnight. Instead, they decline gradually in a process involving five phases:

- Phase 1: Overconfidence

- Phase 2: Overreaching

- Phase 3: Ignoring—or misreading—the signs

- Phase 4: Overcorrecting

- Phase 5: Surrendering

Collins acknowledges that his work shows correlation, not causation—he can only infer why companies failed based on their similarities. He adds that while the five phases are typical in the case studies he reviewed, companies that deteriorate don’t necessarily undergo all phases, nor do they have to go through them in order. Still, companies should be aware of all the harbingers of failure to better guard against them.

“Bad decisions made with good intentions, are still bad decisions.”

Companies generally don’t collapse overnight. Collins writes that there are warning signs when a company is deteriorating, such as fewer customers and lower profits. However, instead of facing problems head-on and pinpointing internal causes of decline, leaders might respond by blaming outside factors like an economic slump, or by choosing to interpret inconclusive data with an overly optimistic eye.

Turning a blind eye to the subtle markers of trouble, a company’s leaders might then take big risks—ones that could have catastrophic consequences for the company if they don’t pay off. Collins again cites the example of Motorola, which started developing Iridium, a satellite phone, before cellular phones exploded onto the scene. The arrival of the cellphone should have given Motorola pause. The evidence was clear: Cell phones were sleeker, cheaper, and offered better coverage than satellite phones. But the company chose to believe that there was still a need for satellite phones and went full speed ahead, funneling $2 billion into the project. In the end, the all-or-nothing bet didn’t pay off, and Motorola filed for bankruptcy.

Aside from careless risk-taking, a company in denial might also undergo reorganization—sometimes multiple times—favoring cosmetic changes that don’t address the real issues over substantive action.

For example, Collins writes that Scott Paper Company, once the leader in the toilet paper market, restructured three times in four years as a response to Procter & Gamble (P&G) gaining ground with its own brand of toilet paper. (Shortform note: Other analysts say that Scott Paper’s restructurings were more complex than a knee-jerk reaction to the P&G threat. Instead, they were likely a response to a combination of factors, including numerous new competitors, an oversaturated tissue paper market, and Scott Paper’s expansion to Europe, Latin America, and Asia.)

“The signature of the truly great versus the merely successful is not the absence of difficulty, but the ability to come back from setbacks, even cataclysmic catastrophes, stronger than before. Great nations can decline and recover. Great companies can fall and recover. Great social institutions can fall and recover. And great individuals can fall and recover. As long as you never get entirely knocked out of the game, there remains always hope.”

Collins contends that if a company still has a worthy goal and the potential to make a meaningful impact, it should commit to putting in the time and effort required to recover and rise. Collins emphasizes that reversing decline isn’t about looking for a miracle cure (such as a savior CEO or a revolutionary new product) but about playing a long, steady game.

This is what Collins prescribes for a floundering company: putting the right people in place, sticking to what your company does best, and being disciplined.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Jim Collins's "How the Mighty Fall" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full How the Mighty Fall summary:

- How formidable companies can lose their footing and fall

- The five phases that lead to a company's downfall

- How to rechart your course if you're facing the threat of failure