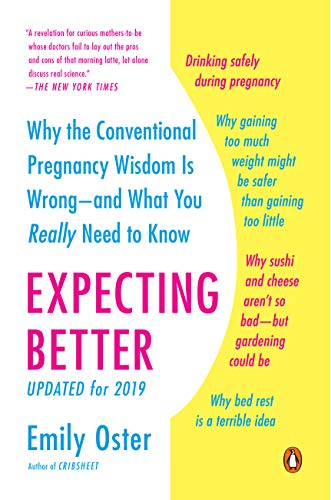

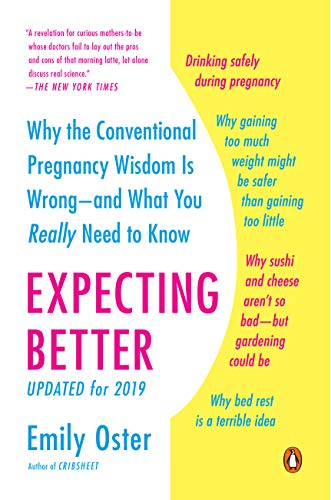

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Expecting Better" by Emily Oster. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

The first thing we’ll discuss is common vices that people generally advise to stop during pregnancy – caffeine, alcohol, and tobacco.

There’s a lot of stigma and confusion around the use of substances in pregnancy. In perhaps the most provocative part of Expecting Better, Oster argues that caffeine and alcohol, in moderation, show no evidence of being harmful to the child.

To cut to the chase:

- Pregnant women can drink 0.5 drinks a day in the first trimester, and 1 drink a day in the second and third trimesters. This is meant to be a maximum limit per day, not an average. Binge drinking is bad – don’t save up your 7 drinks per week for one night.

- 3-4 cups of coffee per day (about 300-400mg of caffeine) is fine.

- Smoking is never OK.

Alcohol in Pregnancy

The common conception is that no amount of alcohol is safe during pregnancy. Oster argues a more nuanced approach is needed.

The main concern of drinking during pregnancy is fetal alcohol disorder, which manifests in cognitive symptoms like developmental delays and learning difficulties.

Here are some guidelines. Binge drinking (more than 5 drinks at a time) is clearly bad. In one study, binge drinkers in the 2nd/3rd trimester were 15-20 percentage points more likely to have children with language delays than women who don’t drink. This is broadly confirmed by the academic literature.

However, this doesn’t automatically scale linearly. In other words, it doesn’t mean that drinking any amount is terrible. Your body is capable of processing a regular amount of alcohol per hour, and below a certain amount, the fetus may be unaffected. Binge drink, and it overwhelms your body’s systems.

Says Oster, “Drink like a European, not like a frat brother.”

How does alcohol in pregnancy actually affect the fetus? Surprisingly, it’s still unclear. Biologically, the body metabolizes alcohol into acetaldehyde, and then into acetate. Oster argues the acetaldehyde is the toxin that impacts development. It also seems that alcohol itself causes oxidative stress, neuronal structural defects, and alterations in gene expression. Either way, the more alcohol and byproducts you have floating around, the more the fetus is damaged.

Weighing the Evidence on Alcohol

The arguments in favor of light drinking not being a big deal:

- Generally, studies show no impact of drinking up to 1 drink per day on these outcomes: preterm birth, child IQ, test scores, behavior problems.

- In fact, many studies find women who drink moderately have kids with higher IQ scores, but this is likely not causal and may instead correlate with education or social factors.

- Evidence on early drinking and miscarriage risk in first trimester is mixed – some results say no relationship, others show twice the risk drinking >4 drinks/week vs no drinking.

- This study didn’t control for nausea, explained in the caffeine section next.

- Generally, Europe is more permissive about light drinking during pregnancy, yet there’s no evidence of greater rates of fetal alcohol syndrome or in population differences in IQ.

(Shorform caveats:

- It’s not clear how mothers with alcohol enzyme deficiencies (aka ‘Asian glow’) may react differently, given that acetaldehyde levels remain elevated at a 5-10x level.

- Not all drinking women lead to kids with fetal alcohol syndrome, much like how ‘only’ 15% of smokers will develop lung cancer. The CDC’s estimate is 2-5% of all children may have fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

- One dissenter, Susan Astley (also an academic) argues that Oster’s studies look at children too early (age 5 and below) but that most cognitive deficits appear at age 10 and later. Furthermore, IQ may appear normal, but language and memory deficits weren’t measured as part of the studies.

- She also argues that 1 of 14 children with fetal alcohol syndrome had a reported exposure of just 1 drink per day, so mild drinking can still lead to FAS. This isn’t as convincing, though, as Oster would argue that the risk of 1 drink per day leading to FAS is quite low.)

Why Myths About Alcohol in Pregnancy Exist

Where does all the confusion around caffeine and alcohol during pregnancy in studies come from? It starts with academic pregnancy studies that don’t meet a standard of rigor.

To figure out how a behavior like drinking affects child outcomes, pregnancy studies typically 1) study the mother’s behavior and categorize them into groups, 2) follow the children’s outcomes over time, 3) associate the outcomes with the original groups.

But a common problem in pregnancy studies is insufficient controls for confounding factors. In other words, things that can affect child outcomes aren’t tracked, and thus entirely different factors can be affecting child outcomes.

Here’s an example. Picture a study where you divide the population of mothers into abstainers and drinkers, then study their kids. If you picture the type of woman who has 0 drinks a week vs 2 drinks a week vs 10 drinks a week, you can already imagine differences in the child’s environment, such as their education, wealth, and location. When the kids grow up, if you find that children of drinkers end up with behavioral problems, it’s unclear whether it was the drinking or the other factors (like household conditions) that made a difference.

Similarly, people worry that coffee causes miscarriages. But women who drink more coffee tend to be older than those who don’t. What if it’s age that’s causing the miscarriages, and not the caffeine?

In one notable study on alcohol during pregnancy, Oster found a startling difference in cocaine use: 18% of women who didn’t drink reported using cocaine during pregnancy, compared to 45% of those having 1 drink per day!

Not only are the poor studies themselves confusing, their results are then cherry-picked by popular media and distorted into a shocking headline: “1 cup of coffee a day causes miscarriages.” Before you know, it myths start perpetuating.

The gold standard study in medical science is the randomized controlled trial, where people are randomized into a control group and a treatment group. Unfortunately, if there is some risk involved, it’s considered unethical to run a study like this – imagine forcing a group of pregnant women to drink 10 drinks per week!

Another reason cautionary guidelines exist is that doctors fear that allowing some laxity could lead to a slippery slope – if they tell someone that one drink a day is ok, then the patient might creep up to 2-3 drinks per day. Oster finds this understandable, but patronizing.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Expecting Better" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Expecting Better summary :

- Why much parenting advice you hear is confusing or nonsense

- The most reliable way to conceive successfully

- How much alcohol research shows you can drink safely while pregnant (it's more than zero)

- The best foods to eat, and what foods you really should avoid