This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Silk Roads" by Peter Frankopan. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What difference does geography make to history? What impact did the East have on the West in the ancient world?

The Silk Roads began in the ancient world, so it’s here that historian Peter Frankopan begins his examination of the history of the connection between East and West. He provides an overview of the Persian, Greek, and Roman empires, particularly in regard to Asia.

Keep reading for Frankopan’s history of the ancient world.

The Ancient World and the Beginning of the Silk Roads

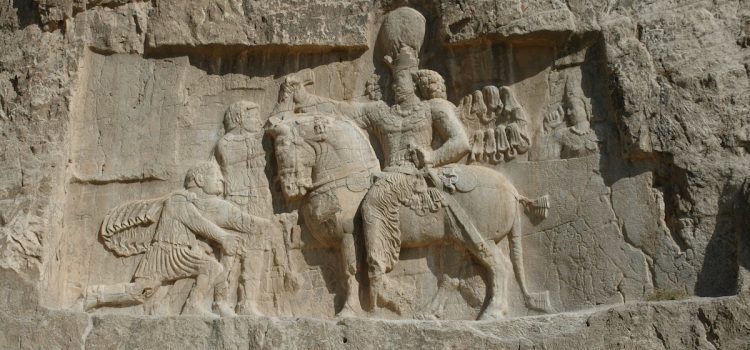

Frankopan writes that a defining feature of the ancient world was the rise and fall of large, multicultural, multiethnic empires, such as the Persian Achaemenid Empire and the Roman Empire. These great empires competed with each other for control over the Central Asian and Middle Eastern heartlands, which, because of their abundant natural resources and strategic location, were these empires’ main sources of economic and military strength.

To understand how history has unfolded over the millennia, we must first understand the history of the ancient world.

| The Economic and Military Importance of the Steppes Part of the reason that this region was so crucial to the success of the ancient empires, from Persia to China, was that these lands were inhabited by nomadic steppe peoples who were important trading partners with the settled peoples of the great empires. The Chinese and Persian empires sent goods like grain, textiles, iron, and bronze to the Scythians and Sarmatians of the steppes in exchange for honey, furs, horses, cattle, and slaves. Access to these trade routes was a vital source of wealth for the ancient empires. Equally as important, the steppe peoples were perhaps the first to master the domestication of the horse, which made them highly skilled warriors and charioteers. For the wealthier polities of Europe and Asia, this was a double-edged sword—the steppe nomads could be fierce and terrifying raiders and invaders, but their military prowess could also be harnessed to the advantage of the wealthy kingdoms, as the steppe nomads were highly valuable mercenaries who could deliver a decisive military advantage for those empires that could cultivate good relations with them. |

The Persian Empire

The ancient Persian Achaemenid Empire (centered upon the area that is now Iran), which first came to prominence in the 7th century BCE, built a powerful and advanced civilization that was highly urbanized, artistically accomplished, militarily dominant, and governed by a sophisticated administrative state. Because of its strategic location, Persia became the crossroads between East and West and the empires of Rome and China. This strategic location would place Persia, and later, the modern nation of Iran, in a starring role on the world stage for centuries to come.

(Shortform note: This first Persian empire—ruled by the Achaemenid dynasty—was the largest in world history at the time of its founding, stretching from Southern Europe to the Indus River. Throughout antiquity, the various empires and dynasties centered around Persia—the Achaemenid Empire, Hellenistic Persia, the Parthian Empire, and the Sassanid Empire—would be the primary rivals to Rome as the Roman state evolved from the Republic to the Roman Empire and finally to the Byzantine Empire.)

The Conquests of Alexander

Frankopan writes that the conquests of Alexander the Great in the fourth century BCE left a lasting legacy. Starting out as the leader of the tiny, obscure kingdom of Macedon (situated mostly in present-day North Macedonia) on the northern fringes of the Greek world, Alexander’s military prowess made him the master of the largest land empire the world had ever known up to that point. His stunning conquests established the expansive Macedonian Empire, which spread Greek and Western Mediterranean culture into Persia, India, and Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan).

Frankopan argues that the movements of Alexander’s armies added to the rich tapestry of language, religion, and culture in this region. This cross-cultural exchange went both ways: Classical Greek religions and gods were known and studied in Persia and India, Greek statues influenced the aesthetic style of Buddhist sculpture, and Indian texts like the Mahabharata shaped later Western works like the Latin Aeneid.

(Shortform note: The three centuries following Alexander’s death in 323 BCE until the emergence of Rome in the late first century BCE are known by historians as the Hellenistic period. This period is considered to be the zenith of Greek cultural power across the world, with Greek influences seen in art, architecture, literature, music, mathematics, religion, and science from the Mediterranean to the Indian subcontinent. The cultural impact of this period is still with us today in works like the Septuagint—the earliest surviving Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, which is the main basis for the scriptures used in the Old Latin, Coptic, Ethiopic, Armenian, Georgian, Slavonic, and Greek Orthodox Christian churches.)

Rome Looks Eastward

Frankopan argues that Rome’s rise from a backwater city-state on the west coast of the Italian peninsula to a regional power happened thanks to its conquests of neighboring Italian city-states during the second century BCE. But it was Rome’s seizures of the rich lands of the East in Egypt and Western Asia in the first century BCE that transformed it into an imperial superpower. In the wake of Rome’s conquests, Roman merchants carved out new trade networks that extended to India and Southeast Asia, bringing luxuries from as far afield as Vietnam and Sri Lanka into the households of wealthy Romans.

(Shortform note: Interestingly, for all of Rome’s expansive conquests and extensive commercial contacts across the ancient East, historians have found scant evidence of close political or economic relations with one of Rome’s few peer empires—the Han Empire of China. There are few documented trade missions or diplomatic visits between the two powers and few references made by writers in either empire about the other. Still, Roman manufactures and coins have been found in China, indicating at least some degree of indirect commercial contact. Historians believe that intermediate powers in Western and Central Asia likely acted as middlemen between Rome and China, inhibiting direct exchange but facilitating indirect trade.)

Frankopan notes that the emperor Constantine (272-337 CE) strengthened Rome’s ties to the East in two important ways. First, he moved the capital of the imperial government east to Constantinople (present-day Istanbul). Second, he was the first emperor to convert to Christianity, marking the beginning of the process that would make Christianity the official religion of the empire.

The conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity represented another influence of the East upon the Roman West, writes Frankopan. Christianity, although synonymous today with the West and Europe, was wholly Asian in origin, with its earliest communities based in Persia, Afghanistan, Jordan, Armenia, and the Caucasus. In fact, the East would remain the focal point of Christianity for centuries afterward, with Eastern missionaries fanning out to Iraq, Syria, and beyond, winning converts from Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, and Judaism.

| The Eastern Roots—and Westward Spread—of Christianity The Eastern Roman capital of Constantinople—home to opulent churches like the Hagia Sophia—was heavily Christian from the beginning, as Constantine made the conscious political decision to found the city with a distinctly Christian identity. Constantine’s decision to make Christianity the Roman Empire’s official religion was a significant turning point, as Christianity was largely unknown in Western Europe for centuries after the fall of Rome. Instead, the peoples of what are today Britain, Ireland, France, Germany, and the Low Countries worshiped a mix of Celtic and Germanic gods. The reach of Christianity in these places during the Roman period had been limited at best. Beginning in the sixth century CE, early medieval missionaries like St. Columba, Augustine of Canterbury, and Remigius began the Christianization of Western Europe, usually by convincing local rulers to convert. |

The Dark Ages in the West

By the mid-5th century, Frankopan writes, the once-mighty Roman Empire in the West would be gone, collapsed under the weight of pressures on its borders from migrating nomadic peoples and a string of disastrous military defeats (although the empire would survive in the East as the powerful and wealthy Byzantine Empire). The empire was replaced by a patchwork of barbarian kingdoms. This was the beginning of the so-called Dark Ages in Western Europe, which saw the population drop precipitously, literacy rates collapse, the disappearance of the integrated global economy, and a sharp decline in the standard of living. Western Europe would remain an economic and cultural backwater for centuries.

| Was Christianity Responsible for the Collapse of the Roman Empire? While there is still much scholarly debate about the precise causes of the fall of the Western Roman Empire, most modern historians concur with Frankopan’s idea that Rome fell because of a combination of internal instability, poor governance, and border incursions by migrating barbarians. However, the English historian Edward Gibbon (1737-1794), who in the 18th century wrote the six-volume The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, argued that it was in fact the empire’s aforementioned conversion to Christianity that brought about the collapse of the great imperial power. In Volume 3 of his work, Gibbon argued that Christianity’s doctrine of “turn the other cheek” sapped the empire’s military spirit, making it weak and vulnerable to outside attack. He also wrote that the massive redirection of public and private wealth toward the endowment of new churches robbed the imperial treasury of much-needed funds, while theological controversies within Christianity gave rise to doctrinal factions and forced the Christian emperors to devote increasing time and attention to resolving religious disputes instead of focusing on matters of state. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Peter Frankopan's "The Silk Roads" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Silk Roads summary:

- Why the Silk Roads have always been history’s crucial connection point

- Why understanding the East is crucial to our understanding of the world

- A history of the Silk Roads, from ancient times to the 21st century