This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "A People's History of the United States" by Howard Zinn. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What’s the history of socialism in America? What have socialists aimed to advance, and why haven’t they been more successful?

In his book A People’s History of the United States, Howard Zinn delves into American socialism, tracing its growth and impact. The Socialist Party of America promoted workers’ rights and government regulation but faced challenges as it pushed for collective ownership.

Keep reading to learn about “the Socialist Challenge” according to Howard Zinn.

The Socialist Challenge

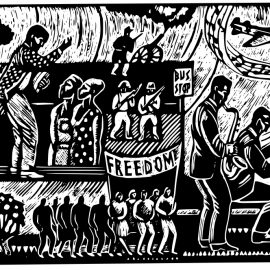

Zinn covers the history of socialism in America in the chapter “The Socialist Challenge” and later chapters of his book. He explains that socialism, or the political and economic ideology promoting collective ownership of property, rapidly gained popularity in late 19th and early 20th century America. Socialists came from a number of backgrounds: They were trade unionists, rural populists, idealistic academics, immigrants, and so on. Their politics were anti-war, anti-imperialist, pro-worker’s rights, pro-government regulation, and pro-social safety nets. Socialists made their largest gains under the banner of the Socialist Party of America (or SPA), a political party founded in 1901.

(Shortform note: Socialism in the US had two main ideological origins: Christianity and secular academia. Christian socialism emerged throughout American Protestant churches in the mid-19th century, especially in the Episcopalian church and among German immigrants. These thinkers cited Christian texts on subjects such as charity, aiding the poor, and collective ownership to argue for modern socialism. The other main origin was in secular academia, as philanthropists, social reformers, and philosophers read the works of 19th century French, English, and German socialists like Charles Fourier, Robert Owen, and Karl Marx. These thinkers used economic, political, and historical analysis to argue that socialism was the ideal way to organize society.)

The SPA also overlapped with women’s rights and women’s suffrage groups of the era, though they weren’t totally aligned; socialists tended to prioritize economic causes over social ones. In addition, while the SPA preached racial equality and allowed people of all races to join, it didn’t advocate particularly hard for Black Americans despite it being a dangerous era for them due to white mob lynchings and horrible working conditions.

(Shortform note: Where socialism overlapped with social issues like racism and sexism, activists were often divided on the question of what should come first—social or economic equality. For example, Black abolitionist and author Peter H. Clark only participated in socialist politics when he believed it was the best route to achieving racial equality. However, he didn’t believe socialism was necessary for racial equality and was willing to collaborate with non-socialist politicians to push for Black rights. On the other hand, Black minister and SPA member George Washington Woodbey believed racial equality could only be achieved in a society with the full economic equality promised by socialism.)

Radicals, Militant Unions, and the IWW

Zinn makes the case that radical organizers were also important for the labor movement. Their violence and serious disruptions to business put large amounts of pressure on capitalists to make concessions. Particularly toward the end of the 19th century under intense economic strain, more radicals emerged. Anarchists like Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman believed that, to achieve the socialist dream of collective ownership, current political and economic systems had to be destroyed. They argued that, in the right context, violence—including bombings and assassinations—was appropriate to achieve these ends.

Founded in 1905, Industrial Workers of the World, or IWW, was a militant union accepting all workers regardless of their industry, race, sex, or immigration status. Instead of negotiating contracts with management like trade unions, the IWW traveled the country supporting and organizing massive ‘general strikes’ of all workers in a given area. They didn’t condone violence except in cases of self-defense, but the nature of their cause meant they often clashed with and were heavily persecuted by law enforcement.

Early Imperial Projects

Around the turn of the 20th century, the US engaged in a number of imperial projects, influencing, controlling, and even conquering other nations and colonies. These accomplished two major goals for elites: First, they created new markets for American goods and new sources of cheap labor and natural resources. Second, they attempted to soothe domestic unrest by appealing to patriotism and nationalism—if everyone thought of themselves as part of a collective American project, they would pay less attention to class divisions within the country.

While elites and major newspapers tended to support these projects, Zinn suggests popular opinion was mixed. Trade unions occasionally supported colonial ventures, believing they would improve business. On the other hand, the Socialist Party was staunchly against American imperialism.

World War I (1914-1918)

In 1914, World War I began—what Zinn describes as a years-long bloody and pointless conflict between European imperial powers. He argues the US joined the war in 1917 to protect American elite financial interests despite mixed or even anti-war public opinion. Before and early on in the war, American elites developed strong business ties with and made large investments in Allied nations. Going to war allowed them to protect these investments.

Zinn explains that the Socialist Party—the main anti-war party—made significant gains in state and local elections during the war.

Internal Divisions

Divides within the labor movement often prevented workers from organizing together, or in some cases, even turned them against one another. These divides were often based on racial, ethnic, or gendered prejudice. Divisions also occurred along ideological lines—the Socialist Party split in 1919 over whether it would support the newly formed Soviet Union. Pro-Soviet and more radical members left the SPA to form the Communist Party USA, halting the SPA’s growing momentum.

The Great Depression

The activity and militancy of the American labor movement tended to fluctuate along with the desperation of workers and the state of the economy. Therefore, the Great Depression—a severe economic downturn that began in 1929 and lasted over a decade—caused labor unrest to skyrocket to an all-time high. For the first several years of the depression, elites in business and government had no clue what to do, leaving the American people to fend for themselves. Communists, socialists, and labor activists organized their communities to support one another, engage in massive, citywide strikes, and pressure elites to make concessions.

World War II (1939-1945)

Zinn argues that American participation in the war was less about fighting fascism and more about protecting imperial power and elite financial interests. He offers several pieces of evidence: First, the US didn’t fight fascism in the years leading up to the war, whether in the Spanish Civil War or during the gradual rise of Nazi Germany. Second, the US didn’t join the war until its imperial possessions were directly attacked.

(Shortform note: Some US elites weren’t just disinterested in fighting fascism, but actually plotted their own fascist coup in 1933 known as the Business Plot. A number of elite bankers and businessmen believed FDR was going to transform the US into a socialist state, and they wanted to replace him—and the US democratic system—with a fascist dictatorship. They planned for Marine Corps Officer Smedley Butler to form a fascist veteran’s association and plan a massive march of disgruntled veterans who would depose the president. This strategy was similar to those used by fascists in Germany and Italy in previous years.)

Regardless of this elite reasoning, popular opinion in the US was mostly pro-war. Many Americans supported the allied cause due to patriotism and anti-Japanese racism.

(Shortform note: American anti-war sentiment looked very different in WWII than it did in WWI. Opposition to WWI was mainly rooted in socialist, communist, pacifist, and anti-imperialist groups who believed the war was a pointless waste of life. While some of these groups opposed WWII as well, a significant portion of the anti-war movement during this period had fascist or antisemitic tendencies instead. These groups weren’t opposed to imperialism or war in general, but instead wanted to keep the US from fighting against the Axis powers.)

Social Movements (1960s-1970s)

Zinn notes there were many other social movements in the ’60s and ’70s on behalf of the vulnerable and oppressed. Movements and the culture of this era challenged conservative social attitudes of previous decades.

(Shortform note: The social movements of the ’60s and ’70s also coincided with an ideological and demographic shift among the American left. Student progressives like the Students for a Democratic Society argued that the university and student activism, not the labor unions and socialist political parties of the past, were the foundation of the left. This “New Left” tended to be younger, more interested in social justice, and less focused on class struggle and building labor power. Meanwhile, the new economic security of the post-war settlement combined with purges of left-wing unions meant that some white workers broke with the left altogether.)

Socialism in America Today

(Shortform note: There has been a small resurgence of leftist and progressive politics in the US since the publication of A People’s History of the United States. Congress members such as Bernie Sanders and Rashida Tlaib identify as democratic socialists, while left-wing organizations like the Democratic Socialists of America have grown significantly.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Howard Zinn's "A People's History of the United States" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full A People's History of the United States summary:

- A bottom-up view of American history focusing on the people, not the politicians

- How Indigenous people, Black Americans, women, laborers, and activists lived

- Why social movements of the 60s and 70s failed to create lasting change