This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Evicted" by Matthew Desmond. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How did housing discrimination come to be? What role did slavery have to play in current-day housing discrimination?

According to sociologist and the author of Evicted, Matthew Desmond, present-day housing discrimination can be traced back to the 1800s. He provides a brief timeline of how this came to be.

Keep reading to learn the history of racial discrimination and housing.

The History of Racial Discrimination

Desmond explains that racism is built into the systems of landlording in the US, and he traces that racial discrimination from slavery in the 1800s up to the present day.

A (very) brief history of housing discrimination in the US includes:

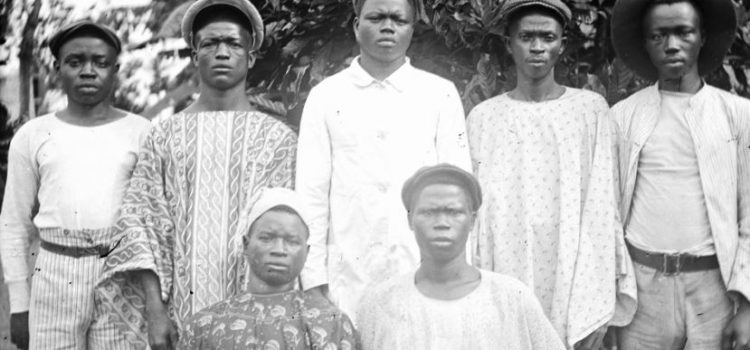

Sharecropping: When the slaves went free after the Civil War, they quickly found that white people still owned nearly all the land, and they had no choice but to go back to work for them as sharecroppers instead of slaves. Instead of payment, workers received a share of what they grew (hence the name sharecropper), giving them no means to leave and seek better opportunities elsewhere.

(Shortform note: President Lincoln foresaw some of the problems that newly freed Black people would face and intended to help them during the postwar Reconstruction period. In And There Was Light, historian and biographer Jon Meacham says that Lincoln’s assassination—less than a week after the end of the American Civil War—was a disaster for the former slaves because Lincoln never got the chance to put his plans for Reconstruction into effect. His successor, President Andrew Johnson, was only concerned with bringing the rebel states back into the Union as quickly as possible, so he allowed white supremacist practices like sharecropping to continue.)

The Great Migration: In the early 20th century, Black families moved in huge numbers to cities in the northern US. Since most of them had no money to buy their own homes, they had no choice but to allow landlords to pack them into dilapidated inner-city neighborhoods, which came to be called ghettos.

(Shortform note: In The Color of Law, historian Richard Rothstein makes a case that segregated neighborhoods like ghettos aren’t just a natural outcome of past disenfranchisement and poverty, but rather are a deliberate result of racist policies at the local, state, and federal levels. For example, in a 1952 court case, the Housing Authority of San Francisco acknowledged that it was intentionally creating segregated neighborhoods to keep Black people contained in certain areas of the city.)

The New Deal: US President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal (a comprehensive economic program enacted from 1933 to 1939) was hugely beneficial to white families, many of whom became homeowners for the first time ever, but Black families were largely left out of these federal programs. The government decided that ghettos were too risky for insured mortgages, and denied them; in other words, centuries of discrimination provided the justification for continued discrimination.

After that came the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the failures of which we’ve already discussed. Desmond sums this up by saying that even though the law now requires people to be treated equally, the history of inequality in the US means that Black people and other minorities are still at a significant disadvantage.

(Shortform note: In brief, Desmond is saying that equal treatment is not fair treatment in a system where some people are already disadvantaged. Race historian Ibram X. Kendi elaborates on this idea in his book How to Be an Antiracist. The crux of Kendi’s argument is that it’s not enough to create laws and policies that are merely non-racist (treating everyone equally, like the New Deal and the Civil Rights Act); for a country like the US to correct its past mistakes, it must embrace antiracist policies that actively work toward fixing the social and economic disadvantages that minorities face. For instance, an antiracist version of the New Deal might have required the government to accept the risk of insuring ghettos, or used federal resources to improve the ghettos so they could be insured safely.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Matthew Desmond's "Evicted" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Evicted summary:

- Why the rate of evictions in the US is even higher now than it was during the Great Depression

- How poverty and eviction each lead to the other

- Ways we can empower citizens to break the cycle of poverty and eviction