This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Grit" by Angela Duckworth. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How do you develop a growth mindset? Is it something you can practice or does it come from experience?

A growth mindset means that you believe you have the ability to improve over time. A fixed mindset is believing that your intelligence and ability to learn are relatively set. In her book Grit, Angela Duckworth says that fixed or growth mindset development is underpinned by three factors: 1) childhood feedback, 2) habits of thinking, 3) experiences of overcoming adversity.

Here are the three factors that determine whether you have a growth or fixed mindset.

Where Does a Growth Mindset Come From?

Duckworth identifies three main influences that determine fixed mindset or growth mindset development: (1) feedback received during childhood, (2) habits of thinking, and (3) experiences of overcoming adversity.

1. Childhood Feedback

Duckworth contends that much of your self-talk echoes feedback you received from authority figures in your childhood. When you did something well, the praise you got, and whether it was for your efforts or for your talent, probably mirrors the language you use today when judging your successes and failures.

Parents, psychologists, and educators who know this strive to praise kids for their efforts rather than for their raw talent. Duckworth discusses some specific ways you can phrase feedback to children that encourage an attitude of perseverance, such as:

- Don’t say: “You’re so good at this!” Say: “Look how hard you worked on this!”

- Don’t say: “Oh well, you tried.” Say: “Looks like that didn’t work. How can you approach it differently next time?”

- Don’t say: “It’s okay if you can’t do this.” Say: “It’s okay if you can’t do this yet.”

Duckworth points to the example of the charter school system Knowledge Is Power Program (KIPP) as an illustration of how educators can foster an attitude of grit with demonstrable results. KIPP teachers praise effort over natural talent and are trained to use grit-encouraging phrases like these listed above. Duckworth reports that the vast majority of KIPP students come from lower-income families, almost all of whom graduate from high school and more than 80% of whom go on to college, and she credits their focus for those successes.

| KIPP’s Successes Are Debated Although Duckworth lauds the KIPP program, some critics dispute the statistics showing its successes. They also contend that the successes that KIPP does have can be explained by factors other than grit training. Critics argue that statistics showing the higher achievements of KIPP students are misleadingly presented. They note that the reported high-school graduation rates ignore the fact that there’s a significant attrition rate of students out of the program before high school—half of the fifth-graders who start at a KIPP school don’t finish eighth grade at one, and of those, only 70% choose to continue in KIPP high schools, suggesting that KIPP high schools end up with only top students to begin with. Critics further argue that where KIPP schools do show improvements in grades, they’re working with a self-selected population of students who hail from families who prioritize education, as indicated by their interest in enrolling their kids or entering them in the lottery for enrollment. Not only that, but the students who leave KIPP schools before eighth grade tend to be the lower-scoring students, indicating that KIPP’s methods are not serving those who need it the most, and that the schools’ achievement scores are skewed because they often shed the lower performers. Therefore, critics argue that KIPP schools don’t have the same mix of disadvantaged students (non-English speakers, homeless children, special needs kids, students with criminal histories, and so on), so that comparisons to public school performances are distorted. To properly assess KIPP methods, these critics argue, a KIPP school would have to take over an entire district, and all of its students, and apply its methods. |

2. Habits of Thinking

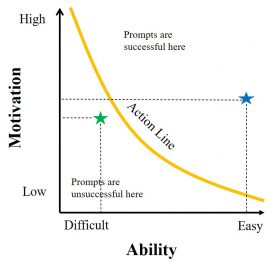

Duckworth argues that optimism and pessimism, as well as growth or fixed mindsets, can be self-reinforcing in either virtuous or vicious cycles.

If you believe your skills can perpetually grow, and that misfortune is temporary and can be fixed, you keep trying to solve problems. When you break through and improve, you further reinforce your positive beliefs, which makes you try even harder next time.

(Shortform note: This corresponds to Duckworth’s earlier discussion of deliberate practice, where she notes that in order to grow your skills, you must continually have small breakthrough moments. Such moments will foster your confidence, leading to optimism and a growth mindset.)

In contrast, if you believe your skills have hit their permanent limits, and you believe life’s problems are caused by those limits, you are less likely to overcome roadblocks – after all, it’s logical to give up if there’s no way out. Your recurrent failures then perpetuate your negative feelings, which further reduce your likelihood of success and cause you to avoid challenges that would have led to growth.

(Shortform note: This explains why people who have learned helplessness during one experience will carry that attitude into their next experience. In the same way that a person suffering from learned helplessness feels they have no control over their failures, so too, do they feel they have no control over their successes, either—they believe that their efforts can only amount to so much because they’re limited by pre-ordained levels of intelligence and talent. Thus, they feel a lack of control over their lives in general and are therefore more likely to give up on a goal.)

3. Experiences of Overcoming Adversity

Duckworth cites studies indicating that subjects who are taught to overcome adversity at a young age—typically around adolescence—are better able to manage adversity later in life. These studies reveal that the opposite is also true—subjects who are taught early in life that they can’t control their suffering carry that lesson with them for the rest of their life.

She references different studies involving both dogs and rats in which the animals were exposed to shocks, and some had a mechanism to stop the shocks but others didn’t. The animals that weren’t able to stop the shocks learned to be helpless, and they responded to challenges helplessly for the rest of their lives. However, those that were able to stop the shocks developed a feeling of resilience, and they were later able to overcome future obstacles. She notes that the effect in both directions was most pronounced when the animals went through the traumatic experience in their adolescence.

Duckworth sees the same patterns in humans. Children and teens who face and overcome adversity are more resilient as adults. She emphasizes that this resiliency is only developed if kids face actual adversity and experience true success against it. It’s not enough to just tell kids that they can get through difficulty—in order for the brain to incorporate this belief into its wiring, kids have to experience the feeling of progress against obstacles.

She notes that the duration of learned helplessness is troubling for kids in poverty, who receive a lot of helplessness experiences and not enough mastery experiences. For kids at an impressionable age, the wiring between failure and mindset can be strengthened repeatedly.

Similarly, on the other end of the spectrum, kids who coast through life without having to overcome adversity can have low grit that makes them crumble under pressure.

Both situations can be reinforced by fixed mindset attitudes from parents or teachers—“you’re just no good at this, and you’ll never amount to anything,” or conversely, “you’re so talented, what a natural you are!” Either way, the fixed mindset doesn’t equip the child with skills for facing future adversity.

| Believing in Control Is the Key to Resilience Experiences of overcoming adversity are the opposite of the experiences of learned helplessness that we discussed earlier. Research on the exact neurological mechanism of learned helplessness sheds light on how early experiences of either success or failure against challenges can affect a person’s future behavior. Studies reveal that a fearful response to stress is actually the brain’s natural state—the region of the brain that releases the hormones that react to stress always acts first. Therefore, it’s not that animals are learning helplessness when they’re exposed to uncontrollable shocks, but instead, they’re learning to stay in their natural state of fear and apprehension. It’s when they’re offered an opportunity to control a situation that a second region of the brain steps in to calm down the more reactive region. Researchers conclude that the process of unlearning helplessness is more about learning that we have the ability to control a situation. In his book Essentialism, Greg McKeown expands on this idea by arguing that learned helplessness happens when we get overwhelmed by our circumstances and forget that we even have an option to choose. McKeown argues that we can see this in children who learn early that certain subjects are difficult and then stop trying to conquer them, or in adults who, at work, feel they don’t have any choice about what tasks they choose to take on, and respond by either becoming demotivated, believing their efforts are futile, or by trying to take on all tasks, and getting burned out. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Angela Duckworth's "Grit" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Grit summary :

- How your grit can predict your success

- The 4 components that make up grit

- Why focusing on talent means you overlook true potential