This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Nudge" by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How does libertarian paternalism create forced choices? Are forced choices problematic?

Forced choices are one of the criticisms of the strategies in Nudge. The argument is that the methods are too paternalistic and make free will meaningless.

Read more about the objections to Nudge, including the issue of forced choices.

Forced Choices and Other Objections

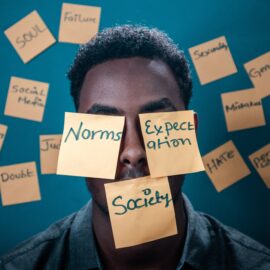

But aren’t nudges manipulative at best, coercive at worst? In the wrong hands, couldn’t the power of nudges be used to move Humans toward deleterious, even destructive, choices? When does libertarian paternalism become just paternalism?

These are legitimate questions, and Thaler and Sunstein attempt to answer them in turn.

Paternalism as a Slippery Slope

One objection to the institution of nudges is: Where do the forced choices end?

Tobacco regulation is a case in point. Information campaigns and surgeon’s general warnings have mutated into astronomical taxes (in certain US states), a rise in the legal age to purchase tobacco products, and bans on smoking in some public spaces. At least in the realm of cigarette use, the government has gradually reduced freedom.

There are three rebuttals to the forced choices “slippery slope” objection:

- The slippery slope objection avoids evaluating libertarian paternalism on its own merits. Does offering tiered choice in retirement plans lead to better outcomes for workers? Does a “mandated choice” regime result in a greater pool of organ donors? If so, then those suspicious of “big government” should suspend their misgivings as long as the choice architecture works. There will always be opportunities later to critique and, if necessary, retrench libertarian paternalistic approaches.

- Through readily available “opt out” choices, libertarian paternalism always offers an escape hatch. Slippery slopes are steepest when options are limited and there’s no easy way to reverse course. Nudges prioritize choice, and so the danger of creeping paternalism is limited.

- Nudges are inevitable. Governments, whether they want to be or not, are in the business of choice architecture—there’s no such thing as a “natural” or “neutral” presentation of choices. Thus it makes sense for governments to nudge people toward the most beneficial choices, as long as choice itself is jealously guarded.

(Although pure neutrality is impossible, there are relative degrees of neutrality. For example, a ballot shouldn’t be designed by a choice architect to favor one candidate over another—rather, the candidates should be randomly ordered and nudges minimized. That is to say, in the case of certain constitutional rights, randomness is acceptable. But when it comes to placing vulnerable people in a health care plan, randomness is both impractical and harmful.)

Nefarious Nudgers

Given how susceptible Humans are to nudges—our bias toward defaults, the ease with which we can be “primed” to make certain choices—it’s obvious that, in the wrong hands, choice architecture can be used against a chooser’s best interest. Forced choices here are not advantageous. (Say, when a company offers you a special introductory rate, then hikes up the price without your knowledge after the introductory period is over.)

The answer to this objection is a hallmark of libertarian paternalism: transparency. If companies are required to advertise their fee schedules in advance, in large rather than fine print, and government officials must publicly report any possible conflicts of interest, we can gauge the choices we’re being offered against any conflicting incentives of the choice architect.

A close relative of transparency is the “publicity principle”—the requirement that any proposed policy be defensible in public. For example, if a government wanted to use subliminal messaging to elect an incumbent, that sort of nudge would be impossible to defend to that incumbent’s detractors. A nudge to promote better saving habits, however, would be.

(Shortform note: Thaler and Sunstein argue that any subliminal messaging, even for a beneficial behavior, would run afoul of the publicity principle, because people don’t like being influenced “without being informed of that fact.” They seem not to recognize that that’s exactly what choice architecture does.)

No Forced Choices

A dyed-in-the-wool radical libertarian will bristle at any constraint on free choice, whether by dint of a particular default or a purposefully designed presentation of choices. An objector of this stripe wishes to preserve at all costs people’s “right to be wrong”—their personal responsibility for all their decisions.

One response to this complaint is that libertarian paternalism’s redistributive effects are minimal. That is, it doesn’t cost the polity much to pick sensible defaults or better structure large choice sets.

Another is that nudges may save those ardent libertarians money and effort in the long run. For example, low-income or elderly people who choose their insurance unwisely may end up relying on the public coffers for their care. Wouldn’t it be better to nudge them toward the best choice in the first place?

Criticisms from the Left

The objections listed up till now parrot those made by critics who lean right politically. But left-leaning observers too may object to libertarian paternalism—for not being paternalistic enough.

Top-down, command-and-control rules—outright bans, mandates, etc.—are anathema to libertarian paternalism, and Thaler and Sunstein do worry that without easy “opt out” features, nudges could be vulnerable to slippery slope objections.

One possible rubric to keep nudges from tipping over into outright paternalism is the notion of “asymmetric paternalism.” This concept prioritizes cost: Do the most one can for the least sophisticated in society while burdening the most sophisticated as little as possible.

An example might be a default national savings program (social security, in some sense, already is one). Under the program, a small percentage of every paycheck would be deposited in a government-sponsored savings account, and the government would match each deposit. The program would be entirely voluntary, though the default would be enrollment. Savvy investors, or those with generous private retirement plans, would likely want to opt out and could do so with almost zero effort. Less financially sophisticated workers, or those without access to 401(k) plans, might opt to stay in, whether on purpose or through status quo bias.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein's "Nudge" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Nudge summary :

- Why subtle changes, like switching the order of two choices, can dramatically change your response

- How to increase the organ donation rate by over 50% through one simple change

- The best way for society to balance individual freedom with social welfare