This article gives you a glimpse of what you can learn with Shortform. Shortform has the world’s best guides to 1000+ nonfiction books, plus other resources to help you accelerate your learning.

Want to learn faster and get smarter? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is the flywheel effect? How does it affect a business’s growth in success and revenue?

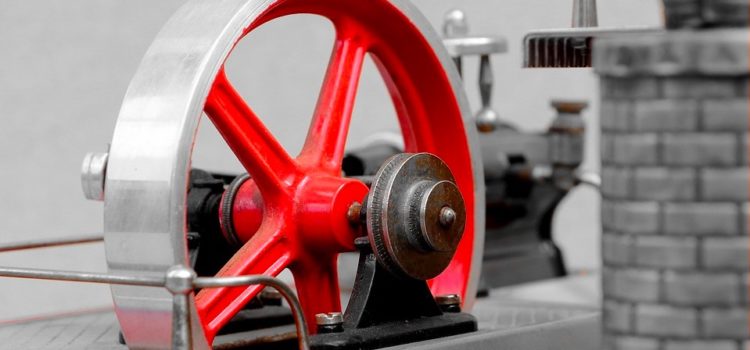

Coined by Jim Collins in his book Good to Great, the term flywheel effect comes from an actual flywheel—a giant metal wheel that takes a lot of work to get moving, but once it does, very little work has to be put into keeping it spinning. The same explanation can be applied to businesses that are built through six essential steps.

Continue reading to learn more about how to ensure your company’s success by using the flywheel effect.

What Is the Flywheel Effect?

The “flywheel effect” captures the overall feeling of being inside a good-to-great company. A heavy flywheel takes an enormous amount of energy to get going—but once it’s spinning, it only takes a small amount of energy to keep it turning or to increase its speed. Companies that went from mediocrity to immense success (also known as “good-to-great” companies) achieve their key strengths steadily and doggedly; they stay patient in the confidence that, with the right cogs in place, the breakthrough will come.

Even though the results are dramatic, flywheels do not result overnight from one concerted action or one flashy launch, or one lucky break. Each step on the road to great takes time—there is no bolt from the blue or miracle moment.

A common excuse of mediocre companies is that Wall Street stifles long-term strategy through its insistence on short-term results. Great companies face the same pressures, but they persist in building their flywheel. The results speak for themselves, earning the grace of Wall Street investors.

Many flywheel examples resulted in billion-dollar companies. Amazon, Walmart, Uber, and Airbnb all used the flywheel effect to catapult their businesses into success.

How Amazon Uses the Flywheel Effect

In the book The Everything Store, Brad Stone documents the rise of Jeff Bezos and Amazon, and includes the secret behind Amazon’s success. In its early days, Amazon’s senior management team had a breakthrough in understanding its business strategy. Jim Collins (author of Good to Great) meets with the exec team offsite and prompts them to consider their flywheel effect:

- Lower prices lead to more customer visits

- More customers increase the volume of sales and attract more third-party sellers

- More third-party sellers increases diversity which increases customers

- More sales means a higher return on fixed costs like fulfillment centers and servers

- Higher return means further lower prices

- This makes executives feel like “they finally understand their own business.”

Early on, they believed that the larger the company got, the lower the prices it could exact from book distributors, and the more distribution capacity it could afford.

In their first shareholder letter: “Market leadership can translate directly to higher revenue, higher profitability, greater capital velocity, and correspondingly stronger returns on invested capital.”

Later in 2001, meeting with Jim Collins, they came up with a renewed virtuous cycle: lower prices leads to more customer visits, leading to more sales, which leads to better returns on fixed costs, which allows for further lowering of prices. More customer visits also led to more third-party sellers, which increases selection and thus increases more customers.

How Wal-Mart Uses the Flywheel Effect

Before Amazon revolutionized lower prices on the Internet, Wal-Mart was setting in-store lower prices that set the standard for future businesses’ pricing strategies. In his book Sam Walton: Made in America, Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton explains that Wal-Mart was judicious about where to open up stores, and it avoided direct competition with other major discount stores for years. Its early strategy:

- Set up stores in small towns. The Wal-Mart model worked in towns even with a population under 5,000 people, while Kmart only chased cities above 50k.

- As Wal-Mart expanded, they established stores within a radius of a day’s drive from a distribution center. They then filled in that territory, town by town, state by state until they saturated the area.

- If customer experience was good (including cost, quality, selection), word of mouth would drive more traffic. Towns would hunger for Wal-Mart to enter.

People tend to simplify the Wal-Mart success story as “they did discount stores in small towns where big players didn’t want to win.” This ignores the heavy competition they faced from local variety stores, the substitute options its customers had (to drive an hour away to a store in the city), and the execution required to expand as successfully as they did.

Sam Walton believed that lower prices brought in more customers, period. Even though a lower markup meant lowered profits, they could more than make up for it with higher volume. In pursuit of lower prices, Wal-Mart omitted frills and passed savings from vendors and efficient operations onto customers.

Uber and Airbnb’s Flywheel Effect

Uber and Airbnb had very similar tactics when they approached the growth of their companies. As detailed in the book The Upstarts, they learned that their cheap rates attracted more riders and travelers, which meant they required more drivers and renters as well.

Uber had natural local virality—back then if you stepped out of a black car in front of your friends, they’d wonder what you were doing.

- More drivers caused less wait time and cheaper fares, which caused more riders to join and more rides to be taken, which stimulated more drivers.

Airbnb had natural international virality built in. Travelers who used the service would consider listing their own places.

- More users encouraged more inventory which encouraged lower prices which attracted more users.

How to Get the Flywheel Spinning

Maintaining a spinning flywheel is the easy part, but getting it to spin is much more difficult. So how did the good-to-great companies do it? Collins provides a tidy chronological diagram that details the companies’ unique traits.

There are six essential parts that make up a company’s flywheel. They act as counterparts that feed off each other, and if one falls off the wheel, the rest go tumbling down and the cycle is broken.

1. Cultivating Singular Leadership

Good-to-great companies have what Collins et al. call “Level 5” leaders. Level 5 leaders are personally humble, almost shy, but highly driven professionally.

They avoid the limelight and tend to credit exterior forces or colleagues for their companies’ successes. Although they’re often personally likable and inspiring, they’re not usually “charismatic.

Their lack of ego enables them to concentrate on one thing and one thing only: the company’s success.

How to achieve it: Collins admits that Level 5 characteristics are likely a product of both nature and nurture and so are difficult to create out of whole cloth; he also doesn’t have hard data to back up any suggestions he might make. His best advice for aspiring Level 5 leaders is to follow the other precepts he outlines. That way, even if you aren’t a Level 5 leader, you’ll at least be acting like one.

Anti-Level 5s

Companies that fail to keep a flywheel effect in motion, unlike their good-to-great peers, were egotistical or braggadocious; brought in from outside the company hierarchy; reluctant to groom successors, and eager to take credit and deflect blame.

The flaws of the failing company leaders all stemmed from their egocentrism. They didn’t groom successors because (1) they wanted to be the “lead dog” and (2) if the company failed after they left, it would be a testament to their personal impact. They took credit and deflected blame because, in their minds, they were the smartest people in the room and couldn’t be wrong.

2. Assembling the Right Team

Good-to-great companies retain the right people before embarking on any specific program.

A good-to-great team is composed of people who care deeply about the company and will argue passionately for the decisions they believe are right (but will come together to support whatever decision is eventually reached).

Avoid at all costs the “genius with a thousand helpers” model; management teams should be composed of independent and critical thinkers, not “yes people.”

How to achieve it: (1) Don’t hire until you’re sure you have the right person; (2) recognize when you need to make a change (whether by shifting a role or letting someone go) and act swiftly; and (3) assign your best people to your biggest opportunities rather than your biggest problems.

3. Unearthing and Facing Facts

Good-to-great companies are evangelical about recognizing market realities and reacting in kind. That said, no matter how dire the facts, they never lose faith that, eventually, they’ll prevail. The key is to be stoic yet hopeful, realistic without turning cynical.

How to achieve it: With the right management team—one comprising sharp, critical thinkers—the facts should never be in short supply. Leaders can encourage truth-telling by: (1) Beginning meetings with questions, not answers; (2) cultivating, rather than stifling, debate among the team; and (3) conducting clear-eyed analyses of mistakes without assigning blame.

4. Thinking Like a Hedgehog

“Foxes” know many things and see the world in all its complexity, whereas “Hedgehogs” know one big thing and order the world according to that thing.

A good-to-great company thinks like a hedgehog by developing a “Hedgehog Concept”—an elegant, easy-to-understand guiding philosophy based on facts—that it adheres to fanatically.

How to achieve it: A company’s “Hedgehog Concept” is derived from the answer(s) to three questions: (1) At what can I be the best in the world? (2) What is my financial engine? And (3) What am I profoundly passionate about?

5. Maintaining Discipline

Good-to-great companies make the jump because they constantly refer to and consistently realize their Hedgehog Concepts. Rigorous adherence to a Hedgehog Concept saves companies from panic acquisitions or misguided projects that can kick them out of the flywheel effect.

Good-to-great companies also lack the administrative and managerial burdens of other companies—with the right people in place and an easy-to-understand Hedgehog Concept, the need for tight management or layers of bureaucracy withers away. Discipline does not mean a tyranny presided over by the executive.

How to achieve it: (1) Allow individuals freedom within a clear framework of responsibility; (2) retain self-disciplined people who are driven to produce results; (3) recognize that a disciplined culture is different from a culture led by a tyrant or disciplinarian; and (4) adhere fanatically to hedgehog thinking. A key technique for staying true to your Hedgehog Concept? Create a “stop doing” list.

6. Using Technology Tactically

For good-to-great companies, technology isn’t the creator of great results but their accelerant.

Rather than follow technological fads and adopt new technology for its own sake, good-to-great companies pioneer particular uses of new technology.

How to achieve it: When evaluating a new technology, the key question to ask is: How does this technology impact my Hedgehog Concept? If it doesn’t, you can safely ignore it and/or accept parity in its use; if it does, you must figure out how you can lead in the application of that technology.

Getting Stuck in the Doom Loop

Rather than hashing out a Hedgehog Concept, evaluating every decision according to it, and advancing their organizations stoically and faithfully, many companies tended to launch flashy new programs in a desperate attempt to build motivation and momentum. They did so reactively and impulsively, without deliberately understanding the key market fundamentals that would increase the likelihood of success with the use of the flywheel effect.

These programs, because they attempted to skip over the buildup phase and proceed directly to breakthrough, invariably failed: They lacked the necessary foundations to produce sustained results. The failing programs were then replaced by further flashy programs, which met the same fate for the same reason, and the cycle began all over again. Thus: the Doom Loop.

Example: Warner-Lambert’s Doom Loop

Between 1979 and 1998, Warner-Lambert, the direct comparison to Gillette, was led by three CEOs, each of whom instituted drastic changes in direction and philosophy: from consumer products to healthcare and back again and forth again.

These moves were driven by CEO ego—each wanted to make his mark on the company and make big new flashy changes—rather than the diligent use of the three circles. In the same period, the company underwent three restructurings, laying off 20,000 workers in the process, and its stock returns bottomed out. Two years later, Warner-Lambert was acquired by Pfizer and ceased to exist as an independent company.

How to Avoid/Escape the Doom Loop

Unlike the flywheel effect, it only takes a short period of time for the doom loop to take effect and wreak havoc on a company’s growth. Collins states that this painful cycle can be avoided by the diligent observance of his six steps. But as seen with Warner-Lambert’s fall, two things are drastically more important than the steps: careful acquisition and consistent leading.

Acquire Deliberately

Acquisitions and leadership changes aren’t intrinsically dangerous—the good-to-great companies featured both in the course of their transformations. But it was the way they used them that spared them the doom loop.

The good-to-great companies executed acquisitions at rates more or less equal to the comparison companies. The good-to-great companies, however, went shopping only after seeing success with their Hedgehog Concept—to turbocharge a flywheel that was already spinning—whereas the comparison companies executed acquisitions to create momentum.

As with technology, great companies use acquisitions as accelerants, not as a hail-mary pass to save the company.

Lead Consistently

Good-to-great companies also saw leadership changes during their transformations—but, due to Level 5 leaders’ tendency to groom successors and create cultures of discipline, transitions from one leader to another were seamless. New leaders at great companies continued to turn the flywheel and accelerated momentum built from the past.

New leaders of failing companies, by contrast, have a habit of stopping an already spinning flywheel in effect.

Harris Corporation, for example, recorded great results under two CEOs whose Hedgehog Concept had the company focusing on printing and communications technology. A third CEO, however, moved the company headquarters from its longtime base in Cleveland to Florida (where he had a house) and, shortly thereafter, abandoned the printing business for office automation, giving up one of the most profitable parts of the company for a pipe dream.

Good money flew after bad, and soon enough a company that had been beating the market by more than 5x ended up 70% behind.

Feedback Loops

The book Thinking in Systems explains that like businesses, stocks experience their own type of loop. Loops form when changes in a stock affect the flows of the stock.

Unlike the doom loop or the flywheel effect, there are balancing feedback loops (also known as negative feedback loops or self-regulation) that keep stocks stabilized and within an acceptable range.

Adhering more to the flywheel concept, there is another case where the system seems to spiral out of control—it either rockets up exponentially, or it shrinks very quickly. When a behavior is persistent like this, it’s likely governed by a reinforcing feedback loop.

We will go over balancing and reinforcing feedback loops in more detail below.

Balancing Feedback Loops (Stabilizing)

In balancing feedback loops, there is an acceptable setpoint of stock. If the stock changes relative to this acceptable level, the flows change to push it back to the acceptable level.

- If the stock dips below this level, the inflows increase and the outflows decrease, to increase the stock level.

- If the stock rises above the acceptable level, the inflows decrease and the outflows increase, to decrease the stock level.

An intuitive example is keeping a bathtub water level steady.

- If the level is too low, plug the drain and turn on the faucet.

- If the level is too high and the water spills out of the tub, open the drain and turn off the faucet.

Your bank account is another example of balancing feedback loops.

- If the stock of money is below what’s acceptably comfortable to you, you’ll likely work more and spend less money.

- In contrast, if you have a windfall and money rises above your acceptable level, you’ll likely work less and spend more.

Balancing feedback loops tend to create stability, and they keep a stock within an acceptable range.

A property of balancing feedback loops is that the further away the stock is from the desired level, the faster it changes.

- A boiling cup of water cools its temperature more quickly than a lukewarm cup of water.

- For your personal finances, you would behave much more extremely if you suddenly became bankrupt, than if you lost $100.

Reinforcing Feedback Loops (Runaway)

As described above, reinforcing feedback loops act more like the flywheel effect because they can very quickly spin out of control. Other than the flywheel effect, they are also known as runaway loops, positive feedback loops, vicious cycles, virtuous cycles snowballing, compound growth, or exponential growth.

Reinforcing feedback loops have the opposite effect of balancing feedback loops—they amplify the change in stock and cause it to grow more quickly or shrink more quickly.

- As a stock level increases, the inflow also increases and the outflow decreases, causing the stock level to further rise.

- As a stock level decreases, the inflow also decreases and the outflow increases, causing the stock level to further decrease.

Here are examples of runaway loops in the positive direction:

- The more people there are in the world, the more they reproduce, which increases the stock of the world population.

- A healthy national economy grows in a reinforcing loop. In a nation, the more factories and people you have, the more you can produce. The more you produce, the more you can invest back in more factories and educate people.

Here are examples of runaway loops in the negative direction:

- In agriculture, plant roots help retain soil. The more that soil is eroded, the fewer roots can grow, which causes more erosion.

- In a natural emergency, a store may have a sale on its goods. The lower the stock of goods like toilet paper, the more fervently people want to buy it, which causes the stock to shrink further.

Takeaways

Unfortunately, many leaders are under the impression that massive success happens overnight—by dint of a splashy initiative, big-ticket acquisition, or cutting-edge technology. These moves all too often fail and lead to further drastic measures such as restructurings and layoffs—which lead to further declines.

Some businesses try to play it safe by staying in a balancing feedback loop, but in the long-term, it means the business may fail because another Amazon or Uber will come along and beat out its competitors. In cases like these, it’s important to find a balance between creative innovations and rash company decisions.

Staying patient and focused is the key to seeing the flywheel effect through—breakthroughs are carefully constructed and the result is an increase in your company’s success.

Want to fast-track your learning? With Shortform, you’ll gain insights you won't find anywhere else .

Here's what you’ll get when you sign up for Shortform :

- Complicated ideas explained in simple and concise ways

- Smart analysis that connects what you’re reading to other key concepts

- Writing with zero fluff because we know how important your time is