This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Anarchy" by William Dalrymple. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How did the mighty Mughal empire fall? What role did the East India Company play in its demise?

While not the direct cause behind the breakdown of Mughal authority, the East India Company benefited from the resulting power vacuum. William Dalrymple explains that the company’s gradual accumulation of control paved the way for the establishment of British rule across India.

Keep reading to learn about the dramatic fall of the Mughal empire.

The Mughal Empire Begins to Collapse (Early 18th Century)

Around the early 18th century, the Mughal empire began to collapse. Dalrymple attributes the early stages of the fall of the Mughal empire to a wide range of forces. First, Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb began enforcing a stricter version of Quranic law, angering the Hindu majority. Then rebellions intensified throughout the empire, as Sikhs, Afghans, and Hindus began seizing territory.

(Shortform note: Many historians argue that Aurangzeb’s crackdown on non-Muslim religions contributed significantly to the empire’s decline because it represented such a hard reversal of the religious tolerance of his predecessors. Many of the Mughals not only tolerated a wide range of religious practices in their kingdoms, but hosted interfaith dialogues between Muslims, Hindus, Christians, Jains, and Zoroastrians. They also subsidized the translation of holy texts. Many Mughal nobles also personally practiced a syncretic form of Islam that recognized commonalities with Hinduism and allowed them to participate in Hindu festivals.)

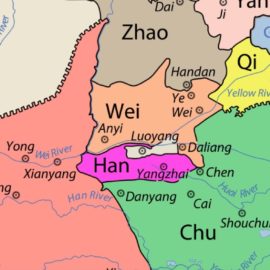

After Aurangzeb’s death in 1707, a dispute broke out over who would succeed him, leading to assassinations, rapid turnover, and conflict between competing Mughal factions. Then a Persian general ransacked the capital of Delhi in 1739, depleting their treasury and damaging the Mughals’ reputation for power. One by one, provincial rulers—the Nawabs—began cutting ties with the capital. The independent provinces stopped sending tribute, undermining the empire’s finances. This fractured India into competing regional powers, inaugurating a period of war and instability.

| Major Factors in the Collapse of Empires Around the World The factors Dalrymple identifies as leading to the Mughal Empire’s collapse have all played crucial roles in the downfalls of some of history’s most notable empires. Here we’ll broaden the historical context by briefly touching on the role of succession disputes, invasions, and financial instability in imperial downfalls throughout the world. 1. Succession disputes: Maintaining clear and agreed-upon rules for the transfer of power is essential for an empire’s stability. After Alexander the Great failed to designate an heir, his Macedonian Empire fell to pieces as his generals fought each other for control. Similarly, the Frankish Empire of Charlemagne and the vast Mongol Empire of Genghis Khan both split into many smaller kingdoms after the deaths of their founders. 2. Invasions: Invading armies also precipitated the downfall of many of history’s great empires. The Byzantine empire ended with a successful conquest by the Ottoman Turks, and the Inca Empire fell with the invasion of the Spanish. 3. Financial instability: Money problems were a major factor in the decline of many empires, including the Western Roman Empire. When Romans couldn’t keep up with the cost of military and administrative expenditures, they began putting less silver in each coin to grow their money supply, causing inflation. The Spanish empire also declined after inflation, but from a different cause: The Spanish mined so much silver from the Americas that silver began to lose its value, devaluing their currency. |

The EIC Rises to Power in Bengal (Early to Mid-18th Century)

While the EIC didn’t cause the collapse of the Mughal empire, Dalrymple asserts that it became the primary beneficiary. No longer constrained by the powerful Mughals, the EIC expanded its trading operations and military capacity, adding forts and recruiting locals to serve as infantry. The EIC set its sights on Bengal, a wealthy province on India’s northeastern coast.

Dalrymple states that the EIC originally began building up military capacity in Bengal to counter the French colonists. This military buildup led to tensions with the Mughal rulers of Bengal. The EIC led a successful military campaign against the Mughal prince that expanded its influence.

The English East India Company Backs Two Coups

Next, the EIC sought to expand its influence in Bengal by backing a coup in Bengal and installing a puppet ruler who would support its interests. The newly-installed Nawab Jafar’s reign went poorly, and the EIC deposed its own puppet (Jafar) in a second coup.

Dalrymple notes that, though the EIC had now carried out two successful coups, it still faced a significant gap in legitimacy. Fortunately for the company, a potential ally had made his way to Bengal and was interested in talks: Shah Alam, a young Mughal prince.

The EIC and Shah Alam reached an agreement: The EIC and Mir Qasim would pledge their allegiance to Alam as the true heir of the Mughal empire. Alam would formally recognize Qasim as the legitimate ruler of Bengal, legitimizing both coups. Then, the EIC would use its military forces to help the young prince march on Delhi and take back his throne. However, after Alam legitimized the coups, the EIC dragged its feet on its end of the bargain. Frustrated with his new “allies,” Shah Alam left Bengal to join forces with Shuja ud-Daula, a Mughal prince ruling a neighboring kingdom.

The English East India Company Overthrows Mughal Rule in Bengal

Dalrymple says the EIC soon grew tired of Qasim’s rule. A much more effective ruler than his father-in-law, Qasim raised taxes to balance the budget and pay soldiers their back wages. He rooted out corruption and built a strong administrative state. Qasim’s competence made him much harder to push around, and the EIC missed the impunity it had enjoyed under Jafar. Additionally, Qasim recognized the EIC as a rival and sought to counter its influence by eroding the privileges it had obtained from Siraj. The EIC voted to formally declare war on Qasim and reinstate Mir Jafar as Nawab of Bengal. Its military campaign prevailed and drove Qasim out of the region.

The English East India Company Repels a Mughal Alliance

According to Dalrymple, the EIC would face one more challenge to establishing complete rule in Bengal: an alliance between three Mughal princes. After his defeat, Qasim fled Bengal with his remaining forces and, like Shah Alam, sought refuge with Shuja ud-Daula. He then proposed an alliance between himself, Shuja, and Shah Alam to drive out the English.

The three princes assembled an enormous force and marched toward Bengal. However, the EIC managed to repel their attack, largely due to a crack in the princes’ alliance. Dalrymple explains that Shah Alam wasn’t fully committed to the alliance. Since Qasim and the EIC had both declared allegiance to him, the young prince saw this as merely a dispute between his subjects—and secretly remained in communication with the EIC. Thus, while Shuja’s troops charged into battle, Shah Alam’s held back, and Shuja’s army failed to defeat the EIC on its own. With the alliance fragmented, the EIC launched a successful counteroffensive and defeated Shuja’s army, cementing its rule in Bengal.

The EIC Rules Bengal (Mid- to Late 18th Century)

Dalrymple states that the EIC established rule over Bengal by carefully maintaining the old Mughal hierarchies. However, EIC men now sat at the top of every hierarchy. The EIC also consolidated its rule by maintaining alliances with the Mughal princes it had just defeated.

The EIC Rises to Power in India (Late 18th to Early 19th Centuries)

Bengal wasn’t the only part of India where the EIC had established itself by the time of the Bengali Famine and Britain’s reassessment of its interests. Dalrymple states thatthe company had also begun asserting itself on the larger stage of regional powers vying for control of the greater Indian subcontinent.

Conflict #1: The Anglo-Mysore Wars (1767-1799)

First, the EIC fought a series of wars against the Mysore Sultanate, leading to a dramatic expansion of its territory and resources. The Mysore Kingdom commanded significant resources. Additionally, the Kingdom had built its own munitions factories and artillery. Lastly, Mysore had forged effective alliances, first with the Marathas and a central kingdom called Hyderabad, and then later with the French.

At first, Mysore succeeded at challenging British power in southern and eastern India, but Dalrymple explains that the war turned against it. Over the next 30 years, under the commands of Warren Hastings, George Cornwallis, and eventually Richard Wellesley, the British took several steps which allowed them to overcome the Mysore Sultanate and conquer its territory.

This victory led to a vast expansion of the EIC’s power. The company’s territory more than doubled, and it grew its total forces to over 155,000 troops, a greater force than the entire military of Britain.

Conflict #2: The Anglo-Maratha Wars (1775-1803)

Finally, the EIC established its rule in India by waging war against the Marathas, a powerful confederacy of Hindu kingdoms based in western India. Dalrymple explains that the Maratha rebellions had been the greatest contributors to the Mughals’ downfall, and that much of the former Mughal empire, including the capital of Delhi, now lay in their hands. The company declared war on the Maratha Confederacy in 1803.

The EIC marched on Delhi and captured it from the Marathas. Dalrymple argues that this was the turning point in the war: Though the Marathas would continue resisting, the fall of Delhi established the EIC as the dominant power in the region.

Consolidation of British Power (Early to Mid-19th Century)

A private corporation, initially created for trade, now controlled half a million square miles and ruled over millions of subjects. Dalrymple explains that, in 1803, the EIC consolidated its power by once again installing a puppet ruler who could lend a veneer of legitimacy to its regime. To do so, the company turned once more to Shah Alam, the exiled Mughal prince who had played a similar role in legitimizing the company’s rule in Bengal and by now was an old man. The EIC tried to publicly frame its rule as a “reinstatement” of Shah Alam and a restoration of Mughal power—though in reality, the old Mughal state was now firmly under British command.

Dalrymple asserts that the EIC’s consolidation of power ultimately cleared the way for British rule in India. Increasing government oversight slowly transformed the company’s administration into a state-run enterprise. The British government officially took over in 1858, after a war for Indian independence stirred fears that the company was losing control of its empire. Nonetheless, Dalrymple asserts, the fall of Delhi truly marked the culmination of the EIC’s rise to power. The period of anarchy following the collapse of the Mughal empire was ending, and a new era of British dominion was beginning.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of William Dalrymple's "The Anarchy" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Anarchy summary:

- How the English East India Company grew during the 17th and 18th centuries

- Why a trading company came to rule most of the Indian subcontinent

- The background, historical context, and fallout from the events in the book