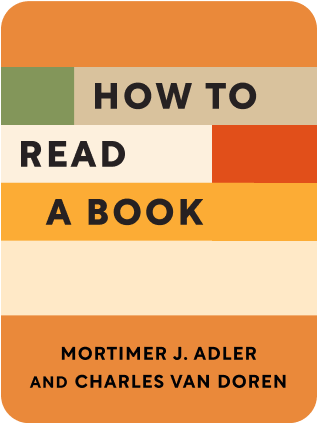

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "How to Read a Book" by Mortimer J. Adler and Charles van Doren. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How and when should you use external resources when you’re reading a book? Is it okay to rely on outside help, or should you try to read a difficult book on your own?

In their book How to Read a Book, Adler and Van Doren believe that you should struggle through a book as much as you can on your own. However, when you really need help understanding the material, there are some tools you can use to aid your understanding.

Below are the external resources that Adler and Van Doren recommend using.

Using External Resources

As much as possible, the authors of How to Read a Book believe you should struggle with the book independently on a first pass. This will help you see the book’s main arguments, rather than getting mired in minutiae like looking up words you don’t know. Therefore, your job is to first understand the book as well as you can without outside assistance. Once you’ve gotten as far as you can on your own, you can consult external resources to help you.

When you use an external resource, understand 1) what you hope to get from consulting it, and 2) the limitations of the resource. Here is how Adler and Van Doren recommend using external resources, and, where relevant, these sources’ limitations:

Dictionary

- You can use a dictionary to look up words you don’t understand; however, remember that the author may use keywords in atypical ways, which is why you must understand terms from the context of the book.

- Use a dictionary only for the most important words that are critical for understanding.

- (Shortform note: It can be difficult to determine whether a word is important enough to look up in the dictionary. One study suggests looking up words only if they’re used multiple times in the text (not just once) and/or if you’re unable to infer their meaning from context.)

Encyclopedias

- These contain facts and not arguments on subjective questions (“What makes man happy?”), other than what people have said about the subject.

- Use it to resolve disagreements about facts.

- (Shortform note: You may also find encyclopedias (and their online equivalents, like Wikipedia) useful for giving context around an issue or event. For example, if you’re reading Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl, you may want to look up the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands for historical context.)

Summaries/Abstracts

- Use these to recover your knowledge about the book after you’ve read it. Do not use these as a substitute for reading the book yourself; the authors believe you’ll develop a bad habit of using these as a crutch, and you’ll get lost understanding a book without a summary. Ideally, you’ve written your own summaries, and you can refer to them when you return to a book.

- According to the authors, there is an exception to this rule: You should use summaries for comparative reading to know if a work will be relevant to your project.

- Note that many summaries have incorrect interpretations or incomplete treatments.

- (Shortform note: The value of a summary depends on your goal as a reader. If you want to understand a particular text in depth, you should read the whole book (multiple times, if necessary). However, if you’re deciding what to read next or simply looking to extract the major ideas from a variety of texts, summaries might be useful.)

Commentaries/Reviews

- Like summaries, Adler and Van Doren believe it’s best to avoid these until after your read-through. Otherwise, you’ll start the book biased and focus on things that support the commentary, rather than working to understand what the author is saying.

- (Shortform note: This is a form of confirmation bias, in which you unconsciously seek out evidence that confirms your existing beliefs and ignore evidence that contradicts those beliefs (or in this case, the beliefs of the commentator). To counteract this effect, try intentionally looking for information that disproves your existing beliefs. The Black Swan author Nassim Nicholas Taleb calls this technique “negative empiricism.”)

When External Resources Are Internal

In general, Adler and Van Doren recommend ignoring external resources until you’ve read the book all the way through and done your best to understand. However, some books make this task impossible because external resources are embedded into the text. For example, many modern editions of Shakespeare’s plays contain extensive notes, translations, and commentary either in footnotes or on the facing page of the text. This placement makes it almost for the reader to ignore this external information. The same phenomenon occurs in annotated versions of classic novels, which are increasingly popular.

Adler and Van Doren may not have anticipated the rise of annotated editions, as they make no mention of them in

How to Read a Book. So how can a modern reader follow their advice? If possible, find an unannotated edition of the book. This may be an older edition. If only annotated editions are available, use a piece of scrap paper to cover the notes while you read. This will help reduce the visual distraction, but it may still take some willpower not to peek!

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Mortimer J. Adler and Charles van Doren's "How to Read a Book" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full How to Read a Book summary :

- How to be a better critic of what you read

- Why you should read a novel differently from a nonfiction book

- How to understand the crux of a book in just 15 minutes