This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Color of Law" by Richard Rothstein. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is exclusionary zoning? How did exclusionary zoning laws turn black neighborhoods into slums?

Exclusionary zoning is the use of racial zoning laws to prohibit Blacks from owning homes in white neighborhoods and vice versa. These racial zoning laws were structured to ensure blacks were confined in densely packed zones adjacent to industrial areas or the pollution industry leading to the deterioration of these neighborhoods into slums.

Read on to learn more about how exclusionary zoning laws disadvantaged African Americans.

How Exclusionary Zoning Laws Segregated Cities

Of course, public housing wasn’t the only means by which government furthered racial residential segregation. Another lever to separate whites from Blacks was racial zoning laws—rules that prohibited Blacks from owning property in white areas (and vice versa). The following sections detail the history of exclusionary zoning in the US and explain how discrimination continued even after racial zoning was declared unconstitutional.

Integration and Its End in the Reconstruction Era

In the aftermath of the Civil War, African Americans gained not only their physical freedom but also a slate of civil and political rights. Formerly enslaved people scattered across the country and, for about a decade, integrated towns and lived relatively unharassed.

These gains were quickly reversed, however, with the election of Rutherford B. Hayes as president in 1877. In order to secure his election, which was disputed, abolitionist Republicans cut a deal with racist southern Democrats: If the Democrats voted for the Republican Hayes, his administration would remove the federal troops occupying the South. (The federal troops were there to keep the peace and enforce the civil rights laws passed by Congress.) The removal of these troops marked the end of “Reconstruction,” the brief period of possibility when Black Americans might have achieved full equality with whites.

Once the federal protection of African Americans—and their new rights—ended, racist localities in the south and elsewhere adopted discriminatory “Jim Crow” laws and enforced those laws by terror. For example, in South Carolina, a white-supremacist group calling itself the “Red Shirts” massacred ten African Americans in the town of Hamburg to scare African Americans from voting. The Red Shirts’ leader, Benjamin Tillman, would serve 24 years in the US senate.

In Montana, where, by 1890, Black settlers were living in every county, African Americans were systematically cleared from white communities. In Glendive, Montana, a 1915 town policy banned African Americans from the town after dark. In Miles City, a significant Black population was forced to flee a violent mob. From 1910 to 2010, the African American population of Helena, the state capital, declined from 420 (3.4% of the city’s population) to 113 (<0.5% of the city’s population).

Effects on the Federal Government

The premature end of Reconstruction affected federal agencies as well as localities. In the wake of the Civil War, African Americans rose to positions of prominence in the federal civil service, occasionally overseeing white office and manual workers alike.

This state of affairs came to an end with the election of white supremacist Woodrow Wilson in 1912. His administration mandated segregation in government offices—separate work areas, separate cafeterias, separate lavatories—and Black managers were barred from supervising white employees.

Buchanan v. Warley and the Persistence of Exclusionary Zoning Laws

In states with smaller populations of African Americans, like Montana, racists could use violence to separate Blacks from whites. In states with Black populations too large simply to run out, racists officials used less frightening, but no less effective, means of marginalizing African Americans. Primary among them were racial zoning laws.

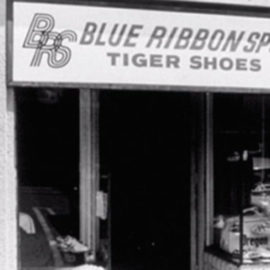

Simply put, racial zoning laws prohibited Blacks from owning homes on white blocks (and vice versa). Baltimore was the first American city to enact an exclusionary zoning policy, and other major cities soon followed suit, including Atlanta, Dallas, Charleston, New Orleans, and Louisville.

In 1917, in Buchanan v. Warley, the US Supreme Court ruled Louisville’s racial zoning law unconstitutional, thus invalidating scores of racial zoning laws across the country. Yet city officials continued to try to segregate their cities by race, using slight variations to evade the ruling. For example, in Richmond, Virginia, officials used a state law banning interracial marriage to adopt a new zoning law: A person of a particular race couldn’t live on a street where he or she couldn’t marry the street’s majority race. The US Supreme Court declared this law unconstitutional in 1930.

Similar gambits repeated themselves in West Palm Beach, Florida, and Birmingham, Alabama. Both cities had racial zoning laws on the books through the mid-twentieth century. In Kansas City and Norfolk, VA, discriminatory zoning practices persisted until the 1980s.

Further Evasions

Elected officials who accepted Buchanan as settled law found other ways to segregate their cities: namely, economic zoning and industrial zoning.

Economic Zoning

The first way officials achieved racial residential segregation without explicitly mentioning race in their laws was through economic zoning—ordinances designed to limit neighborhoods to single-family homes affordable only to middle-income people. Because African Americans had been historically and systematically discriminated against in the job market (see Chapter 10), many were lower-income, and so could only afford housing in apartment buildings—structures that were banned by these ordinances. The result was that areas zoned for single-family homes stayed or became white while areas that allowed multiple-family dwellings stayed or became African American.

This strategy was blessed by the federal government. In 1921, the Harding administration convened an advisory committee to develop and disseminate a manual explaining economic zoning. Although race wasn’t mentioned in the manual, several members of the advisory committee were ardent segregationists; one would later say that economic zoning was necessary to maintain racial separation.

The federal government’s position was echoed by academic experts. The most prominent scholar of administrative law at the time argued that the best reason for economic zoning wasn’t the creation of single-family neighborhoods but rather the exclusion of African Americans.

Example: St. Louis

A particularly illustrative example of economic zoning occurred in St. Louis. In 1916, a planning engineer named Harland Bartholomew set about classifying all the structures in the city by type to ensure neighborhoods retained their character. For example, if a district mostly consisted of “single-family residential” or “industrial” properties, that district was coded accordingly, and future construction had to be consistent with the category Bartholomew had assigned it.

Although the project was superficially race-neutral, its purpose was, explicitly, to prevent African Americans from being able to move into predominantly white neighborhoods; Bartholomew even said himself that his goal was to keep “colored people” from moving into the “finer residential districts.”

Using these zoning laws, city planners consciously divided the city, allowing more affordable multi-family residences only near industrial areas and preventing those structures from being built in areas containing mostly single-family homes. The upshot was that African Americans were confined to slums—densely packed areas that either contained, or were adjacent to, polluting industry.

Economic Zoning and the Courts

Inevitably, economic zoning laws were tested in the courts. And, for the most part, they were upheld as nondiscriminatory. A 1926 Supreme Court ruling, occasioned by a zoning ordinance in a Cleveland suburb, held that the building of apartment houses in single-family areas was a nuisance. This ruling overturned a district court ruling that acknowledged economic zoning’s not-so-subtle racial purpose.

Even as late as 1977, the Supreme Court affirmed zoning ordinances that furthered de facto segregation. In that year, the Court upheld a zoning ordinance in a suburb of Chicago that outlawed multifamily residences everywhere but a single outlying commercial district. Despite the fact that the local resistance to multifamily residences had an explicitly racial motivation—letters published in local newspapers argued that the zoning ordinance would keep African Americans out of the neighborhood—the Court ruled the ordinance constitutional.

Industrial Zoning

The second way officials segregated their cities in the wake of Buchanan was industrial zoning—the zoning of particular areas for noisome industrial plants and factories. City planners would zone areas near African American neighborhoods for industry, thereby reducing property values (because of the noise and pollution) and ghettoizing the African Americans that lived in those areas (due to their inability to sell their homes and move elsewhere).

The location of industry in or near African American neighborhoods had a second effect: turning those neighborhoods into slums. One example of this outcome can be found in Los Angeles. Although there was some industry in South Central LA in the 1940s—when the area became predominantly African American—it was still largely residential. But that same decade, the city began using “spot” rezoning ordinances to move automobile junkyards and commercial factories into the area. The result was the deterioration of the neighborhood.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Richard Rothstein's "The Color of Law" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Color of Law summary :

- How racial residential segregation is the result of explicit government policy

- The three reasons why racial segregation is so difficult to reverse

- The steps that could lead to a more integrated and equitable society