This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "A Moveable Feast" by Ernest Hemingway. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Who were Ernest Hemingway’s friends in Paris? What was his relationship like with each of these people?

In his memoir, Ernest Hemingway describes the friends and acquaintances he made while living in Paris in the 1920s. He knew many of the famous writers and poets in the area which Gertrude Stein nicknamed the “Lost Generation.”

The following recollections are taken from his memoir A Moveable Feast.

What Is “The Lost Generation”?

Hemingway often visited Gertrude Stein after returning from assignments for newspapers and wire services, to update her on anything funny that happened to him on these trips. When he wasn’t updating her on his travels, he sometimes dropped in to talk about books—he liked to read so that he wasn’t thinking about his own writing all the time.

Hemingway was reading D.H. Lawrence and Aldous Huxley, but Stein didn’t care for either of these writers, calling them boring, dead, and preposterous. She suggested he read the work of Marie Belloc Lowndes instead. There were only two writers whom Stein admired, who hadn’t admired her as well: Ronald Firbank and F. Scott Fitzgerald. If you brought up James Joyce with her more than once, you wouldn’t be invited to her flat again.

Stein also contended Hemingway was part of a lost generation—those who had fought in the war and were now drinking themselves to death. This made Hemingway think about Stein’s own shortcomings on his walk home, and he wondered whether he was part of a lost generation or whether she was lost herself. He realized that all generations were lost in their own way—affected by different things while growing up.

Ezra Pound

Poet and modernist thinker Ezra Pound was one of Hemingway’s closest friends during his time in Paris. They discussed their work extensively.

Pound and his wife Dorothy had a studio on Notre-Dame-des-Champs where they displayed art from Pound’s friends. While Hemingway didn’t like the art, he admired Pound for supporting his friends’ work. One day, Pound asked Hemingway to teach him to box, and Hemingway tried his best, as English writer Wyndham Lewis looked on. Afterward, they had a drink; to Hemingway, Lewis looked like a nasty man with eyes of an “unsuccessful rapist.”

Pound, though, was extremely kind and helpful. He had friends in the arts who he tried to help. He was particularly concerned that since the poet T.S. Eliot was working at a bank, he didn’t have enough time to write.

Pound had a charitable initiative, which he called Bel Esprit, that aimed to raise enough money for Eliot to become a full-time writer. Natalie Barney, a rich American, became the patron. Hemingway was also enthusiastic about the plan and helped to find money. After Eliot published The Waste Land, he became better known and could give up his bank job, thanks to the Bel Esprit campaign and to the fact that he found his own patrons.

Ford Madox Ford

Although he traveled in much the same circles as the English novelist Ford Madox Ford, Hemingway found him unpleasant. In this section, he describes an odd encounter with Ford.

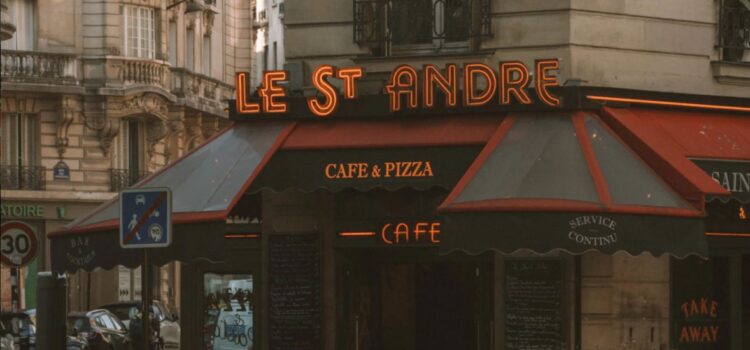

Hemingway’s favorite café near his apartment in Paris was the Closerie des Lilas. He liked it because it didn’t attract patrons wishing to be seen—most people kept to themselves and were, Hemingway thought, academics. There weren’t many poets there.

As Hemingway sat in the cafe one day, Ford Madox Ford, the English novelist, joined him. Hemingway didn’t like Ford and tried to avoid him at social events, but Ford had stopped at his table to insist that Hemingway and his wife come to a club with him on the weekend. While they talked, a thin man walked by and Ford gave him a nasty look. He then reported to Hemingway that the man was Hilarie Belloc, a British/French writer. Hemingway didn’t understand why Ford had been rude to Belloc, as Hemingway would have liked to meet him.

Ford described Belloc as a cad and himself as a gentleman. Hemingway asked him if Ezra Pound, a mutual acquaintance, was a gentleman, and Ford said no because Pound was an American. Very few Americans were gentlemen, according to Ford. Henry James was almost a gentleman, and Hemingway was not a gentleman, but not a cad either.

After Ford left, a friend of Hemingway’s sat down, and the thin man passed by again. Hemingway reported to his friend that the man was Hilaire Belloc, to which his friend replied that the man wasn’t Belloc but Aleister Crowley, an English mystic and occultist nicknamed “the wickedest man in the world.”

Ernest Walsh

Hemingway met poet Ernest Walsh at Ezra Pound’s studio. Intense and very Irish, Walsh arrived at the studio with two American women he’d met on a ship returning from the U.S. The women were boasting about how much Walsh was paid for his poetry. Hemingway noticed that Walsh looked visibly ill, or “marked for death” (doomed like a character in a movie).

Walsh took Hemingway out to a very expensive lunch, where they discussed a rumored $1,000 prize to be given by The Dial, a literary magazine that Walsh helped edit. After a few drinks, Walsh announced that Hemingway was going to receive the prize. The more Walsh talked, though, the more convinced Hemingway became that he was being conned.

Their conversation drifted from the talents of James Joyce to Hemingway himself. In discussing Joyce’s poor eyesight, Hemingway noted that everyone had some sort of health problem. Walsh responded that Hemingway didn’t seem to have any health issues. Rather than being “marked for death,” Walsh said, Hemingway appeared to be “marked for life.”

As time went on, Walsh became increasingly ill; eventually, he had hemorrhages and had to leave Paris. Before leaving, he asked Hemingway to take charge of The Dial’s printing in Paris, which Hemingway did happily. He had enjoyed Walsh’s company and respected Walsh’s co-editor despite feeling conned.

Years later, Hemingway discussed Walsh with James Joyce, who asked if he had promised Hemingway the award. Hemingway said yes, and Joyce said Walsh had promised it to him as well. Hemingway told Joyce about the women in Pound’s studio bragging about Walsh’s money, which Joyce found amusing.

Jules Pascin

Hemingway and Hadley had a son in 1932, and Hemingway had to work hard to support both of them. One evening, he felt especially proud of himself because he’d worked all day even though he’d rather have gone to the track. When he stopped at a bakery after work, the proprietor, Mr. Lavigne commented that he’d seen Hemingway working at the Closerie des Lilas but didn’t interrupt because he seemed so focused.

Hemingway then walked to the Dôme Café, where he joined Jules Pascin, the painter, who was sitting with two women who were models. Pascin was very drunk and asked Hemingway whether he wanted to have sex with one of the models (the two were sisters). The four of them drank and joked together for a while, and the model whom Pascin had offered to Hemingway posed in ways that showed off her figure. She invited Hemingway to have dinner with them, but he extricated himself and went home to his wife.

Although Pascin later hanged himself, Hemingway remembered him as jovial, the way he was that night at the Dôme.

Evan Shipman

Thanks to his access to books at Shakespeare and Company, Hemingway was a voracious reader—enjoying to various extents the work of Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Stephen Crane, Stendhal on Waterloo, and many more. Having the time to read in Paris was vital to Hemingway, and no matter how poor he was, he always felt happy to be able to read so much and take books on trips.

Hemingway also appreciated discussing books with other writers—for example, the poet Evan Shipman. One day after playing tennis with Pound, Hemingway checked in at home and learned that Shipman had stopped by and was now waiting for him at a nearby cafe. He had a big whisky with Shipman, and they talked about Dostoevsky—namely, about how he could be a terrible writer but also evoke such intense feelings. Shipman called Dostoevsky a “shit” and said that he wrote best about “shits and saints.” Also, he said reading Dostoevsky made you angry.

At the cafe where they talked, Shipman knew a particular waiter well; the man was concerned about maintaining his job under new ownership. Shipman often visited the waiter’s house outside of Paris, where they worked together in the garden. Shipman was a generous friend.

Ralph Cheever Dunning

The poet Ralph Cheever Dunning was a wild character who had a drug problem, but Pound admired his poetry because he wrote without caring whether it was publishable, and Pound enlisted Hemingway to help take care of him.

One day, Pound sent Hemingway a message requesting that he come and see Dunning because he was dying. Dunning had taken opium and stopped eating, but although he looked horrible, Hemingway determined that he wasn’t dying. They eventually took Dunning to a clinic where he could detox, and Pound solicited the help of poetry lovers to pay the bills.

Meanwhile, Pound entrusted Hemingway with a jar of opium in case Dunning needed it in an emergency. At one point Dunning climbed onto the roof of the place he was staying and wouldn’t come down, so Hemingway gave the opium to the concierge, but Dunning came down without it. Hemingway then went to Dunning’s door and handed it to him in person, but Dunning angrily threw it back at him and started throwing milk bottles at him as well. He wasn’t interested in the opium.

Years later, Hemingway wondered what had become of Dunning, but Shipman told him that Dunning’s fate should remain a mystery. Shipman believed that the world needed unambitious writers like Dunning who honed their craft without caring whether they were published or acclaimed.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Hemingway spends much of the book describing his encounters with F. Scott Fitzgerald, the novelist’s problems with alcohol, and his writing—Hemingway considered The Great Gatsby to be great literature and Fitzgerald became Ernest Hemingway’s friend for life.

Hemingway first met Scott Fitzgerald in a cafe. Fitzgerald was accompanied by Dunc Chaplin, who was a pitcher for the Princeton Baseball Team. Fitzgerald had a boyish face with wavy hair and a high forehead. His eyes were friendly and his mouth looked like a woman’s. Fitzgerald praised Hemingway’s work to Chaplin.

As they drank, Fitzgerald began asking Hemingway questions about his personal life, like whether he had sex with his wife before they were married. Hemingway said he didn’t remember, but Fitzgerald continued to press him. At this point, Fitzgerald’s face started to tighten, and he suddenly looked very ill. Hemingway was alarmed and said they should get him to a doctor, but Chaplin said Fitzgerald always looked this way when he drank. The next time Hemingway saw him, Fitzgerald acted as though everything were normal, and alcohol didn’t affect him strangely, although he appeared to be remembering a different night than the one he had spent with Hemingway.

Another time, Fitzgerald discussed the faults of his earlier books with Hemingway—his insistence that they were no good led Hemingway to believe that his latest book, The Great Gatsby, was very good. Fitzgerald said the book wasn’t selling, but he had heard that there were good reviews. He was happy with the book, but upset that it wasn’t selling well. When it came to writing stories, Fitzgerald often revised them to make them commercially viable. Hemingway was horrified by this, and he called it whoring. He wanted Fitzgerald to simply focus on writing the best stories that he could.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ernest Hemingway's "A Moveable Feast" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full A Moveable Feast summary :

- Ernest Hemingway's autobiography about his life in Paris between 1921 and 1926

- How Hemingway knew so many other great authors of the time

- Why F. Scott Fitzgerald was a toxic yet valuable friend to Hemingway