This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Think Like a Rocket Scientist" by Ozan Varol. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

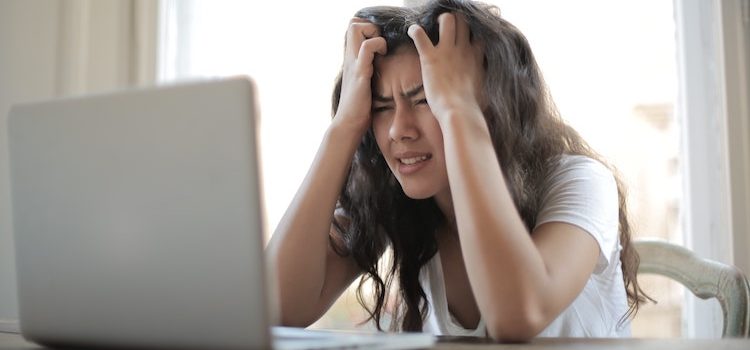

What is the Einstellung effect? How does it prevent you from solving problems?

The Einstellung effect is when you have such a fixed idea about problems that you can’t see new solutions. Basically, you default to the same old solutions because you think it’s the same old problems. Your brain needs a reset so that you can see each problem individually and in fresh ways. The book Think Like a Rocket Scientist offers two suggestions to get unstuck.

Read more to learn about the Einstellung effect and effective problem-solving.

The Einstellung Effect

According to Varol, turning an impossible dream into an achievable goal is often a matter of reframing the problem. In fact, Varol argues that defining the problem can be even more important than coming up with a solution because it’s so easy for the brain to go into autopilot mode when it comes to solving problems that we’ve faced in the past. We get stuck in our conception of a problem to the point that it prevents us from seeing new solutions. Scientists call this “the Einstellung effect” (“Einstellung” is German for “set,” as in “set in one’s ways”).

(Shortform note: Research shows that the Einstellung effect can set in quickly—even after just five trials of a novel problem. To counter the effect, take frequent breaks when you’re solving a series of similar problems. These breaks serve as “pattern interrupts,” which reset your brain and allow you to see each problem with fresh eyes.)

How Rocket Scientists Solve Problems

According to Varol, to counter the inertia of familiar solutions and defeat the Einstellung effect, scientists reframe the problem. For example, when the tripod landing gear failed on a previous Mars mission, the Mars Rover team had to come up with a way to avoid the same mistake. The most important step was to reframe the problem: Instead of asking, “How can we improve the existing landing gear?” they asked, “How can we safely land a rover on a distant planet?” This reframe led to the development of an innovative airbag system that cushioned the rover as it fell to the Martian surface. (Shortform note: Varol cites this as an example of reframing a problem—however, it’s also an example of reasoning from first principles. Instead of focusing on the specifics of the current solution, the Mars Rover team dug down to the root of the problem: landing an object on another planet without breaking it.)

How You Can Solve Problems

Here are Varol’s suggestions for overcoming the Einstellung effect and reframing problems:

1) Differentiate between strategy and tactics. In Varol’s view, strategy is the what; tactics are the how. You implement a strategy using tactics—but the tactics can change if the need arises. To reframe a problem, try refocusing on the strategy and make sure you’re not getting stuck on an individual tactic. (Shortform note: This distinction between strategy and tactics is similar to the distinction between goals (the long-term what) and systems (the short-term how) that James Clear describes in Atomic Habits. However, Clear disagrees with Varol—he argues that focusing on goals/strategy can create problems because they are one-time achievements, so it’s better to focus on implementing solid systems/tactics, which will set you up for consistent success.)

Varol recommends reexamining your tactics by talking to people who are unfamiliar with your field. They’re not beholden to the tactics, so they’re more likely to see other ways of accomplishing your overall strategy. (Shortform note: In Dare to Lead, Brené Brown argues that this is one reason diversity is so crucial in a successful organization. A diverse group brings people with different perspectives together who may be able to spot outdated tactics that you don’t see.)

2) Beware of “functional fixedness,” which happens when we fixate on how something (a tool, an object, or a tactic) is “supposed” to be used. For example, if you’re experiencing functional fixedness, you may look at a shoe and see only a protective covering for a foot. On the other hand, if you break out of functional fixedness, you might see that a shoe can also be a tool for hammering a nail or even opening a bottle of wine.

To combat this, Varol advises focusing on form, not function. By refocusing on what something is rather than what it does, you can train your brain to see its full potential.

| Practice Creative Reframing Varol doesn’t mention a critical way to boost your ability to reframe problems: Practice coming up with creative ideas. For example, you might try the “In What Way” exercise, in which you choose two dissimilar objects and try to list as many similarities between them as possible. This encourages you to examine each object’s form and function separately. For example, you might ask, “In what way is a stapler like a director’s chair?” Answers include: Both contain hinges; both have parts that are made of metal; both could be found on a film set. |

Reframing the problem in these two ways can help you overcome the Einstellung effect and get unstuck.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ozan Varol's "Think Like a Rocket Scientist" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Think Like a Rocket Scientist summary :

- How to solve problems like billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk

- Why you should treat your ideas like scientific hypotheses

- How to bounce back from failure and avoid complacency after success