This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog" by Bruce D. Perry and Maia Szalavitz. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What are the effects of childhood trauma on brain development? Do early experiences of stress have long-term consequences?

The effects of childhood trauma on brain development include changes in feelings of empathy, intensified fight or flight responses, and a dissociative response to stress. Children may experience some or all of these symptoms, and understanding where they come from is key to beginning treatment.

Keep reading to understand how childhood trauma affects the brain and why childhood trauma is different from adulthood trauma.

Understanding Childhood Trauma

Traumatizing experiences are deeply distressing events that can include the loss of a parent or close loved one, witnessing a violent crime, living through an intense accident or disaster, or experiencing neglect or abuse. These events can cause trauma, though they don’t always do so. Whether a distressing event causes trauma depends on many factors, especially the timing of the event and the support the person receives from others. Here, we will discuss the effects of childhood trauma on brain development.

(Shortform note: We can infer that “trauma” refers to both the traumatic event and the trauma response (the ongoing reaction to the event). This is also how it’s commonly used in the mental health field. Additionally, trauma may not always come from a specific event: Ongoing stress can also cause a trauma response. This type of prolonged trauma may include experiences like being bullied or feeling powerless, often having to give others news that could traumatize them, hostile work environments or job insecurity, and incarceration.)

The general belief in the 1980s was that trauma didn’t impact children as heavily as it impacted adults. Children were seen as resilient; psychiatrists assumed they could recover from trauma quickly and easily. However, researchers’ work has since shown that trauma impacts children more strongly than it does adults, and that the earlier in life it occurs, the more likely it is to have severe and long-lasting consequences. Childhood trauma is quite common: around 40% of children in America undergo one or more traumatic experiences before they reach adulthood. Additionally, studies suggest that over 8,000,000 children in America suffer from psychological conditions induced by trauma.

(Shortform note: Other estimates suggest the rates of childhood trauma are even higher than this: Some put the figure at closer to 50%—though some sources place the number lower, at 25%. Other research suggests that more than two-thirds of children experience trauma.)

| Historical Shifts in the Medical Field’s Understanding of Children The “kids are resilient” idea seems to be falling out of favor even outside of child psychiatry circles. Recently, a tweet pointing out that many “resilient” children grow into adults in need of therapy gained viral popularity on social media, suggesting a social trend toward recognizing the unique needs of children. Still, medicine and psychology have a history of failing to adequately understand children and their needs. In The Psychology Book, the authors explain that the field of psychology was founded in the mid-1800s—but it wasn’t until the 1930s that psychologists recognized that children had different cognitive processes than adults, leading to the founding of developmental psychology. Physical medicine has been similarly late to the game. Until the 1980s, medical professionals generally believed that infants couldn’t feel pain—which meant infants were often put through painful, invasive procedures with no anesthetic. Today—much like the modern understanding of childhood trauma—medicine recognizes that infants likely feel physical pain more intensely than adults or older children. |

The Developing Brain

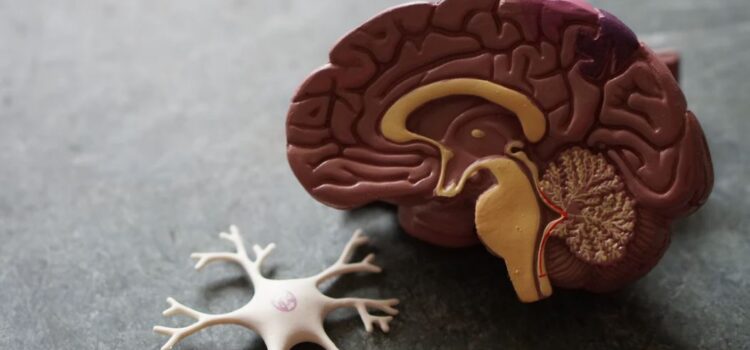

To understand childhood trauma and its long-term impact, we first need to understand how our brain develops in childhood. The brain develops sequentially, starting with the most simple regions, then grows more complex with age. The brainstem develops first, followed by the diencephalon, the limbic system, and finally the cortex.

The brainstem, the simplest region, regulates the most essential bodily functions, including body temperature, heart rate, breathing, and sleep. The diencephalon and limbic system are responsible for our emotional responses, and the cortex is responsible for higher-level thinking functions like language, abstract thinking, and decision-making.

However, this neural development doesn’t happen automatically. The brain must be stimulated in certain ways and at certain times in order to trigger its growth. In infancy and early childhood, that stimulation comes primarily from caregivers. As we age, we also begin to receive neural stimulation from our interactions with peers and people outside our caregiving circle. Neglect can leave the growing brain without this stimulation, while abuse and other traumatizing experiences can change the brain’s responses to such stimulation. This is because this neural stimulation is what teaches us to regulate our brain and body’s stress response, which, as we’ll see in the next section, determines how we cope with traumatizing events.

| The Brain Starts to Develop Before Birth Research suggests that sequential brain development begins before birth and continues throughout adolescence. Each of the main brain structures (the brainstem, diencephalon, limbic system, and cortex) forms during the embryonic and fetal periods of a baby’s development, but the higher-level structures—such as the cortex and certain limbic structures like the hippocampus—are initially very primitive. However, even in utero, neural stimulation from the senses prompts brain growth. Just seven weeks after conception, the fetus’s first neurons begin to form. These neurons allow it to make small movements that provide neural stimulation that facilitates further development throughout the rest of the pregnancy. And while the most basic brain structures are still the ones largely in charge by birth, even the high-level cortex begins taking on some functions by then—such as controlling breathing and how the baby responds to stimuli in its environment. |

The Stress Response

Because of its critical role in the experience of trauma, understanding the body’s natural stress response is essential to understanding all the other principles of childhood trauma. The most primitive parts of our brain control the stress response, which is a physiological reaction that allows us to respond to threats in our environment. Generally, thera are two types of stress responses: hyperarousal and dissociation.

Hyperarousal prepares the body to flee or fight a threat by flooding it with chemicals like adrenaline and noradrenaline. Dissociation prepares the body to endure physical harm by slowing its major functions and releasing natural opioids to numb pain. Both of these responses also shut down higher-level brain functions, like abstract thinking and impulse control, in favor of functions that are likely to help us survive the current threat.

This is why traumatized children often struggle with focus: Their brains are constantly on the lookout for threats, which means they’re paying close attention to things like people’s tone of voice and demeanor (which can signal that someone’s about to try to hurt them) and can’t pay attention to other things like classroom lessons or lectures about their behavior.

| Unpacking the Complexity of the Stress Response There are different theories on the stress response and how it can manifest. Hyperarousal and hypoarousal (the dissociative response) are often broken down into more specific types of responses (often beginning with the letter “F”), and these subtypes help us understand the many forms the stress response can take and recognize the behaviors that accompany them. The fight and flight responses are commonly known types of hyperarousal stress response, but other theories describe additional types such as the freeze response. This is when the body becomes immobilized in response to a threat. Some identify the freeze response as hyperarousal, others as hypoarousal, and still others as a combination of the two. The flop response looks similar to the freeze response, except that the body goes limp, faints, or is overwhelmed with fatigue (as opposed to freezing, where the body stops moving but remains tense). Flopping is thought to be a type of hypoarousal. There are two additional “F”s: feign (or fawn) and flood. Feigning is when someone tries to please or appease the source of the threat (such as an abuser or attacker), often by pretending to befriend them. And flooding is when someone is flooded with emotions in response to a threat. |

The Stress Response in Infancy

The caregiver-infant interaction lays the neural foundations for coping with and regulating stress later in life. When we’re infants, every new stimulus is stressful, including things as basic and essential as physical touch or hunger. A vital part of infant development is receiving care that teaches us how to respond to and process these new stimuli (or stressors).

When an infant’s stress response system is activated, it cries—a reaction that’s designed to elicit a response from caregivers who attend to the infant’s needs. For example, if the infant is hungry, the caregiver responds by feeding; if the infant is afraid or uncomfortable, the caregiver soothes them with holding, cooing, and rocking. These behaviors relieve the infant’s stress response by determining the source of the distress and then eliminating it.

This interaction creates an association in the infant’s brain between social interaction with the caregiver and an activation of the reward centers in their brain, resulting in a feeling of pleasure. This association is what makes us enjoy and crave social interaction, and it’s essential for developing empathy (as we’ll discuss later). If the infant doesn’t receive the proper caregiving response, they won’t develop these associations.

Trauma at Later Ages: the Dissociative Response

This shows that stress and trauma in infancy could have long-lasting impacts. Trauma later in childhood could impact children’s behavior differently.

Dissociation as a Stress Response

Often, when children’s stress response systems become overactive due to excessive stimulation, physiological checks on the children show that their heart rates were elevated, a sign of the fight or flight response.

However, the body has other ways to respond to stress depending on the situation. In cases where a threat is too great to escape or fight off, the brain may activate a dissociative response—a response particularly common in children, who often lack the physical or mental means to fight or flee from a threat. Dissociation prepares the body to endure physical harm: It slows breathing and reduces blood flow and heart rate, which can help the body avoid bleeding to death, and the brain releases natural opioids that can alleviate pain and help the person detach psychologically from what’s happening to them.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Bruce D. Perry and Maia Szalavitz's "The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Boy Who Was Raised as a Dog summary:

- How trauma impacts the developing brains of children

- Case studies of child abuse and neglect, as told by a child psychiatrist

- An explanation of the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics