This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Leadership: In Turbulent Times" by Doris Kearns Goodwin. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

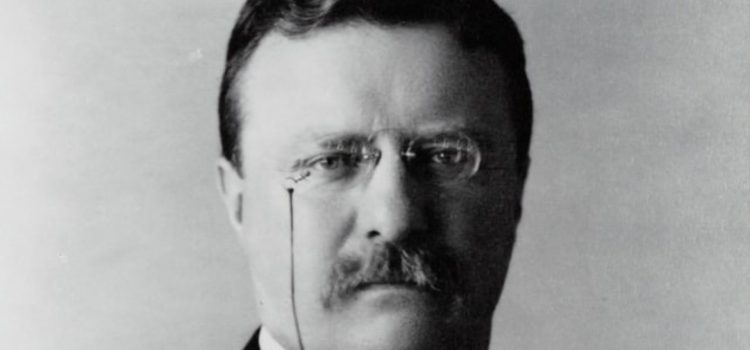

What is Theodore Roosevelt known for? What was the key turning point in Roosevelt’s leadership?

According to Doris Kearns Goodwin, Teddy Roosevelt’s greatest achievements as a president would not have happened if it wasn’t for his family tragedy. He was stricken with immense grief, which made him dive deeply into his work, setting a chain of events that were instrumental in Roosevelt developing qualities that were essential to how he handled the 1902 coal strike.

Here’s how Roosevelt’s crisis taught him bias to action.

Theodore Roosevelt and How He Learned to Act

According to historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, Teddy Roosevelt, who led the country from 1901 to 1909, struggled with the limits of presidential power and ultimately expanded it in a major way: He was the first president to ever settle a labor dispute. He was instrumental during the coal strike of 1902, when coal miners and mine owners faced off in a months-long strike that threatened to plunge the nation into crisis.

(Shortform note: Following the precedent Roosevelt set, several later American presidents also got involved in labor disputes. However, these interventions weren’t always as well-received as Roosevelt’s. Notably, during the Korean War, President Harry S. Truman determined that striking steelworkers were damaging the war effort and seized steel mills—a move the Supreme Court later declared unconstitutional.)

Goodwin contends that Roosevelt’s decision to intervene during this strike is evidence of courage and a bias towards action—both of which he developed after experiencing his own personal crisis.

How Roosevelt’s Crisis Taught Him to Act

Goodwin explains that Roosevelt’s crisis began in February 1884, when both his wife and mother died on the same day. This personal crisis quickly expanded into a professional one: Roosevelt tried to deal with his tragedy by diving into his work as a New York state assemblyman, but his bullish methods of pushing laws quickly alienated his colleagues, leading Roosevelt to leave the legislature.

(Shortform note: Roosevelt chose to deal with his grief by returning to work, but many modern Americans are forced to return to work while in the throes of grief because they have only a few days of bereavement leave. If you’re facing this situation, you can ensure that, unlike Roosevelt, you remain productive and can relate positively to your colleagues by following experts’ tips for returning to work while grieving, like taking regular breaks and setting boundaries regarding what you’ll discuss with colleagues.)

In response, Goodwin argues, Roosevelt made two moves—the first of which led him to develop the courage he’d demonstrate during the later coal strike of 1902. Goodwin explains that Roosevelt embarked on a journey of healing by spending two years at a North Dakota ranch. This was both a physical and spiritual journey. Roosevelt was never a physically gifted man, but he regularly exposed himself to physical challenges at the ranch. He was often afraid of these physical challenges—but by repeatedly facing them anyway, he learned to be brave and not let fear stop him.

(Shortform note: According to High Performance Habits author Brendon Burchard, there are four types of courage. By exposing himself to physical challenges, Roosevelt developed psychological courage, which is when you overcome a personal fear or anxiety and grow. The other three types of courage are physical courage (when you put yourself in physical danger for a worthy cause), moral courage (when you stand up for your beliefs in the face of adversity), and everyday courage (when you maintain positivity in the face of uncertainty).)

Goodwin contends that Roosevelt’s second move—or rather, moves—demonstrates Roosevelt’s newfound willingness to act when you can because you may never get another chance. Goodwin argues that, prior to his personal crisis, Roosevelt had a plan: He wanted to become president, and he was willing to bide his time and wait for the next move that would get him there. But the loss of his wife and mother made Roosevelt aware that time was never guaranteed. As a result, he developed an attitude that boiled down to: “Do things now.” He took any job he was offered and did his best to solve the issues it presented as quickly as possible—prioritizing efficiency and ignoring the traditional, slow-moving channels, much to the chagrin of the bureaucrats who championed them.

As evidence of Roosevelt’s new attitude, Goodwin points to the fact that he took several jobs after returning from North Dakota and how he handled said jobs. For example, as New York City police commissioner, Roosevelt’s main task was to fight the rampant corruption in the police department. Roosevelt used several creative tactics to try to transform the department’s culture into one that valued integrity. Most famously, he donned various disguises and traversed the city at night to find and discipline patrolmen who were slacking off.

| Can Leaders Change Institutional Cultures? As Goodwin notes, Roosevelt ultimately failed to create lasting changes in the New York Police Department because he tried to enforce an unpopular law that alienated voters and led them to re-elect corrupt politicians who recorrupted the NYPD. But if he hadn’t tried to enforce this law, could he have transformed the NYPD’s culture? Experts are divided on this: Some, like Leading Change author John P. Kotter, argue that it’s impossible to change a culture top-down; rather, it must develop organically over time. Other experts argue that leaders do play a significant role in reshaping the values, practices, and assumptions that constitute an organization’s culture—although they recommend creating a vision, implementing it, and then disciplining those who don’t meet it (like by punishing patrolmen who are slacking off) rather than starting by disciplining people who don’t meet the new vision. |

How Roosevelt’s Crisis Affected His Leadership

Goodwin contends that both Roosevelt’s courage and willingness to act were essential to his decision to intervene in the coal strike of 1902. As Goodwin notes, Roosevelt faced a major dilemma during the coal mine workers’ six-month strike to protest dismal labor conditions. Roosevelt needed the mine workers and owners to reach a resolution: At the time, the Northeast relied on coal for fuel during the winter, and without it, the region would plunge into crisis. However, as president, Roosevelt technically didn’t have the legal standing to intervene in the situation.

Despite this reality, Roosevelt chose to intervene anyway—ultimately ending the strike and setting the precedent that presidents could help solve labor disputes. These decisions were only possible, Goodwin argues, due to the courage and bias towards action that Roosevelt learned after his crisis. Roosevelt was brave enough to step outside of the traditionally accepted presidential role, and he chose to protect the American public as he saw fit, despite the lack of precedent—and in doing so, redefined the previously private issue of labor disputes as a public interest issue in which the president could get involved if necessary.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Doris Kearns Goodwin's "Leadership: In Turbulent Times" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Leadership: In Turbulent Times summary :

- How great leaders grow from tragedy and personal challenges

- How FDR’s polio diagnosis helped him lead the country through the Great Depression

- Why Lyndon B. Johnson’s heart attack instrumental to the civil rights movement