This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Molecule of More" by Daniel Z. Lieberman and Michael E. Long. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How are dopamine and impulsivity related? What causes impulsive behavior?

Dopamine and impulsivity are connected because dopamine makes you want things and makes you feel like achievements will make you happy. Once you understand how this works, you can see how this causes impulsive behavior when unchecked.

Here are some ways that dopamine affects emotions and behaviors.

How Dopamine Affects Desires and Decisions

Dopamine and impulsivity are deeply connected. Dopamine is a powerful and versatile chemical, and it is part of what causes impulsive behavior.

First, dopamine doesn’t help you judge whether you should want something—in other words, whether it’s actually good for you. For example, looking at social media produces a steady stream of dopamine, but there are probably better uses of your time than scrolling through your feed for hours.

Second, dopamine makes you want things, but it doesn’t help you enjoy those things once you have them. That’s why people tend to want whatever they don’t have—they constantly strive for greater achievements, more recognition, more wealth, more possessions, and so on.

For instance, someone who has a big collection of video games might impulsively buy the hottest new release and enjoy a quick hit of dopamine, only to leave that game collecting dust on a shelf next to everything else they haven’t played.

| Breaking the Cycle of Dopamine Urges These dopamine-driven impulses can lead to a pattern of behavior that’s commonly referred to as the hedonic treadmill. This is an endless cycle of chasing something we think will make us happy, experiencing a brief moment of pleasure from attaining it, then chasing the next thing once the pleasure wears off. Psychologists call it a treadmill because we’re constantly “running” after happiness, but we keep winding up in the same place emotionally. There are several ways you can get off the treadmill: Ask, “Do I need this?” When you want to buy something for yourself, take a step back and ask if it’s something you need or just something you want. Another way to approach this is to ask, “Will this be good for me?” If so, it may be something you need; if not, it’s only something you want. (However, when answering this question, remember that recreational activities like reading, traveling, and creative hobbies are important to your health—so don’t dismiss something as a want just because it’s not directly helping you toward a fitness or career goal.) Practice gratitude. Instead of thinking about what you don’t have yet, remember and appreciate what you do have. Examples might include your health, family and friends, job, home, and accomplishments. Find pleasure in simple things. You can find contentment and tranquility without having to spend money or a great deal of effort. Instead of chasing after big, showy possessions and accomplishments, remember the pleasure of simply taking a walk or watching your favorite TV show. |

How Dopamine Balances Itself

Fortunately, your brain has a system to suppress and control those dopamine-driven impulses—and it does so by using more dopamine.

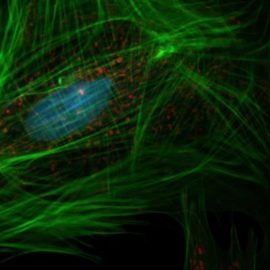

This regulatory system is found in the frontal lobe (the part of your brain that handles reasoning and long-term planning). While the dopamine produced there still creates feelings of motivation, in this case, the dopamine motivates you to think things through and figure out the best way to get what you want.

For example, suppose you’re feeling hungry; dopamine will motivate you to find something to eat. However, the dopamine in your frontal lobe will also motivate you to decide what to eat, how best to get it, prepare it, and so on. This also lets you do things like balancing your urge to eat junk food with your desire to reach long-term health goals. Without that regulatory system, you’d just take whatever food is most convenient and immediately eat it, regardless of the impact on your health.

| How Brain Structure Contributes to Impulsive Behavior If we have this regulatory system in place, why do we still act impulsively? One reason is because of how our brains are structured; reasoning is one of the slowest and weakest brain functions we have, while dopamine-fueled desires can affect us much more quickly and strongly. In Behave, Sapolsky explains that the human brain has three different “levels”: core functions (base level), emotions (middle level), and reasoning (top level). Furthermore, lower levels can bypass and override the levels above them. That’s why, when you’re feeling a strong emotion, it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to reason your way out of feeling it—in fact, you might find it hard to use reasoning at all. If the emotion is strong enough, you might impulsively act on it before you even have the chance to consciously think things through; it bypasses your top-level brain functions completely. For example, if you’re extremely hungry, your desire for food might be so strong that it overrides any sense of logic or thoughts about your long-term health goals. As a result, you might impulsively buy fast food or eat whatever junk food is nearby. By contrast, if you’re only slightly hungry, you’re still able to use your reasoning to make wiser health choices—and dopamine in your frontal lobe can assist with this, as Lieberman and Long describe. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Daniel Z. Lieberman and Michael E. Long's "The Molecule of More" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full The Molecule of More summary:

- How dopamine drives ambitions, determines love, and influences thought

- What exactly dopamine is and how it affects us

- How some chemicals, like serotonin, actively work against dopamine