This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Stamped from the Beginning" by Ibram X. Kendi. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

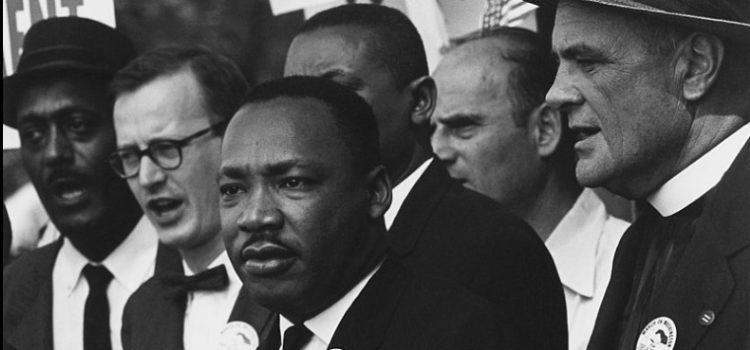

Did the Civil Rights movement succeed in eradicating racism? Was racism really over with the passing of the Civil Rights Act?

By the mid-20th century, civil rights activists were finally making some headway toward political and social change. According to Ibram X. Kendi, many anti-racist changes only succeeded because of white self-interest, and as a result, they had the side effect of reinforcing old racist ideas and inspiring new ones.

Here’s what really lies behind the success of the Civil Rights movement, according to Kendi.

Civil Rights as Self-Interest

Following World War II, the U.S. wished to be seen as the leader of the “free world” and win influence in global politics and economic markets—including those that were emerging as various countries won their independence from their former European colonizers. In this context, Kendi argues, President Dwight Eisenhower realized that the US’s obvious racism and prejudice would hurt the country’s global image—especially as the rest of the world began to see the violent oppression and abuse of Black activists at the hands of white law enforcement officials in the South.

(Shortform note: In other words, just as self-interest can lead to racist policies that then lead to racist ideas, so too can self-interest lead to antiracist policies and ideas. For example, in Hidden Figures, Margot Lee Shetterly says that during World War II, government research groups began hiring women and Black people out of necessity because so many white men were serving overseas. Likewise, Shetterly argues that during the Space Race, it became obvious that segregation limited the US’s potential for scientific achievement. In both cases, leaders began to support Black and female equality—not because they initially held antiracist or antisexist ideas, but because national interest compelled them to change their policies.)

Kendi suggests that this political self-concern helped open the door for integration in the 1950s and new civil rights laws in the 1960s. But when Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, he says, they inadvertently created a new racist myth. Kendi argues that by proclaiming equality without addressing the historical and ongoing inequities that put Black people at a disadvantage, the act suggested that Black people were now on an equal playing field and that if they didn’t excel in equal measure to white people, their failure to do so proved their fundamental (racial) inadequacy.

(Shortform note: In So You Want to Talk About Race, Ijeoma Oluo argues that the playing field still isn’t level today. For instance, she points out that non-whites face discrimination when applying to college, making them less likely than their white peers to earn college degrees. This in turn disproportionately limits job prospects for non-white people, who face further discrimination from employers if their names “sound Black” or “ethnic.” Oluo says that these disadvantages lead to a cascade of socioeconomic consequences for non-whites, who face a racial wealth gap, housing discrimination, and more.)

The Myth of Postracial America

Did the Civil Rights movement succeed at eradicating racism?

As the post-Civil Rights era settled in, Black people gained legal protections and society moved away from open racism and discrimination. Leaders then started talking about a “color-blind” or “postracial” society. The idea of color-blindness seems appealing—it implies that nobody notices or cares about racial differences, which in turn suggests that racism is no longer an issue. But Kendi points out that not seeing race means not seeing the racial disparities that exist because of racism. He concludes that color-blindness and postracialism are inherently racist concepts because they obscure racist policies and their effects.

Moreover, he points out that postracialism undermines antiracist positions by delegitimizing any accusations of racism. As Kendi explains, postracial logic says that people who criticize racist policies or behaviors are themselves racist because they’re insisting on racial differences even though race isn’t an issue anymore. Kendi suggests that this is a new way of accusing someone of “playing the race card”—that is, exploiting their status as a racial minority as a political tool.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ibram X. Kendi's "Stamped from the Beginning" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Stamped from the Beginning summary:

- How enslavers convinced themselves that slavery benefited slaves

- Why most antiracist reformers harbored racist thoughts

- How to achieve an antiracist society