This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Determined" by Robert Sapolsky. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Do we have free will, or is everything predetermined? What difference does it make?

In Determined, Robert Sapolsky says that decades of research have led him to two conclusions. First, people do not have free will. Second, accepting this fact will empower us to create a better world for everyone.

Read on for an overview of this book that deals with a matter that scientists, philosophers, and theologians have been debating for millennia.

Overview of Determined by Robert Sapolsky

Our overview will begin by explaining determinism—the theory that every event is predetermined—and its implications for human behavior. We’ll then briefly discuss various scientific fields like chaos theory and quantum mechanics; for each, we’ll explain why some people believe that field proves the existence of free will (or at least the possibility of it), and Sapolsky’s rebuttals to those theories. Finally, we’ll explore why Sapolsky believes that determinism compels us to create a fairer, kinder world and why he wants you to act as though free will doesn’t exist, even if you’re not totally convinced yet.

Robert Sapolsky is a neuroscientist who’s spent decades exploring the biological and neurological causes of human behavior. He researches such varied topics as how stress affects the brain, what drives people to commit acts of violence, and why religious beliefs are so widespread and enduring. He is widely published in academic journals and has also written several popular science books, the most famous of which is Behave, which was the precursor to Determined. Robert Sapolsky is also a professor of biology, neurology, and neurosurgery at Stanford University.

The Predetermined Universe

Sapolsky begins by explaining determinism: the theory that every event, from the most important to the most trivial, is the direct result of whatever happened immediately before it. Those occurrences, in turn, were due to what happened immediately before them, and so on. In short, determinism theorizes an unbroken web of events that reaches all the way back to the beginning of the universe.

Determinism also means that whatever happened was the only thing that could have happened at that moment, because it was determined by the moment beforehand. For example, think about what happens when you throw a ball: The moment you let go, the place where that ball will land has already been determined by the force of your arm, the angle of your throw, the wind, and countless other factors. The ball can’t simply choose to land someplace else—all it can do is travel along its predetermined path.

This section will explain two major reasons why Sapolsky believes free will doesn’t exist:

- By definition, free will means making decisions without any influences—otherwise, you’re simply reacting rather than acting freely. However, this is impossible because you’re always being influenced by your genes, experiences, and surroundings.

- Whatever “choice” you make is the only choice you could have possibly made, based on everything influencing you at that exact moment.

We’ll also discuss how scientific advancement supports Sapolsky’s theory that people aren’t in control of their own actions.

Determinism and Human Behavior

Applying the theory of determinism to human behavior would mean that anything a person thinks or does is simply a response to what happened the moment before. Moreover, it’s the only response they could possibly have—just like the ball from the previous example can’t land someplace besides where it’s going to land, the person can’t do something besides what they’re going to do. Innumerable different factors, both personal and environmental, come together to create that one inevitable outcome.

To give just a few examples of personal influences: Someone’s genetics, their physical and mental health, and their mood all affect their behavior. Even things that seem unimportant, like whether they’ve eaten recently, play a role; you probably know from experience that being hungry makes you irritable and more likely to snap at people.

Environmental influences on a person’s behavior include socioeconomic status, education, culture, friend groups, and how their parents or guardians raised them. Again, seemingly trivial things can affect their thoughts and actions—for instance, people tend to get short-tempered when it’s hot out.

Furthermore, each of those influences was itself influenced by whatever came before it. Therefore, determinism once again theorizes a string of causes and effects going back to the very beginning of time and insists that everything people do is part of that unchangeable string of events.

Argument #1 for Determinism: Influenced Choices Aren’t Free Choices

The crux of Sapolsky’s argument that human behavior is deterministic is: Your brain determines what you do, and all of the countless influences we discussed determine what your brain does. Therefore, what you experience as “making a choice” is really your brain processing all of the things influencing you at that moment and calculating a response.

For instance, you might think that you chose to have steak for dinner, when in reality you were being influenced by low iron levels that made you crave red meat and a sign advertising the local butcher shop that you saw on your way home from work. Then again, perhaps money’s too tight for steak, so you decided to make meatloaf instead—that’s another factor (your finances) further influencing the decision that you believe you made freely.

Argument #2 for Determinism: You’d Always Make the Same Choice

Sapolsky says another fundamental concept of determinism is that identical situations will always lead to identical outcomes. This logically follows from the idea that events are predetermined by the events leading up to them; if that’s true, then the same causes will always lead to the same effects.

We’ll apply this concept to human behavior with a thought experiment: Imagine that you’re standing in your kitchen right now, deciding what you want to eat. Now imagine that scenario playing out across an infinite number of identical realities, with an infinite number of identical versions of you. Would all of those “you”s choose the same snack?

If even one copy of you chose differently from the others, that would prove the existence of free will; since the starting conditions are exactly the same, free will is the only thing that could lead to a different outcome. Conversely, the deterministic answer is that every one of those infinite versions of you would make the exact same decision, thereby demonstrating that free will is a myth.

The Shrinking Role of “Free Will”

While discussing determinism and free will (or the lack thereof), Sapolsky points out that scientific research has repeatedly found underlying reasons for things that we used to believe were the result of personal choices. This suggests that “free will” is just a catch-all explanation to fill the gaps in our understanding of people’s behavior.

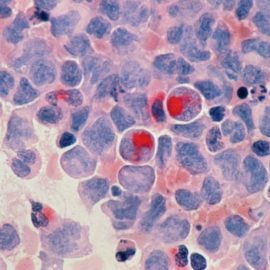

Therefore, the more we learn, the less we attribute to this nebulous concept of free will. For example, now that we know about conditions like clinical depression and ADHD, we understand that people with those disorders have chemical imbalances that affect their behavior, and they aren’t just choosing to be lazy or careless.Following that trend to its conclusion, Sapolsky believes that if we somehow became omniscient, it would become clear that free will doesn’t exist. With no gaps in our understanding of human behavior, there would be no need for such a concept, nor would there be any way to fit it into our worldview even if we wanted to.

Scientific Theories of Free Will

Now that we’ve explained Sapolsky’s strictly deterministic view of the universe, we’ll explore several science-based theories of free will and Sapolsky’s counterarguments to those theories.

This section will cover:

- Compatibilism: the theory that objects must behave according to deterministic natural laws, but people can choose their own actions.

- Chaoticism: the theory that human behavior is so unpredictable that it must be the result of free will, because no natural laws can explain it.

- Emergent complexity: the theory that free will can’t be explained by the behavior of individual brain cells but can be explained by the interactions between those cells.

- Quantum indeterminacy: the theory that because subatomic particles don’t follow the laws of determinism, people (who are made of such particles) can behave indeterminately as well.

Theory #1: Compatibilism

First of all, Sapolsky says many people believe that determinism and free will can both be true; in other words, that they’re compatible with each other. These compatibilists believe the universe is deterministic and runs according to unchangeable laws of nature, but people are still able to make decisions within the constraints of those natural laws. In short, the compatibilist view is that determinism narrows your options, but it doesn’t narrow them down to just one option like Sapolsky believes.

For instance, you can’t flap your arms and fly to the grocery store, because doing so would break the laws of physics. However, you’re still free to choose whether to walk, bike, or drive to the store.

The previous section has already covered Sapolsky’s argument against compatibilism: He says that it seems like you’re deciding what mode of transportation to use, but you’re really being influenced by countless factors like convenience, how much energy you have, how much time you can spend on this trip, and how much storage space you’ll need. After considering all of those different elements you come to a single conclusion, which he says is the only conclusion you could possibly have reached under those specific circumstances.

Theory #2: Chaoticism

Chaoticism—also called chaos theory—is a cross-disciplinary field of science and math that studies complex systems and how small changes can have enormous, unpredictable effects on those systems over time. People who favor the chaotic theory of free will say that humans are very complex and therefore unpredictable. They argue that there’s no scientific or mathematical way to link causes (what someone is experiencing) with effects (what they decide to do because of it), which leaves free will as the only possible explanation.

Arguments Against Chaotic Free Will

Sapolsky says that the chaotic theory of free will has several glaring flaws.

First of all, proponents of this theory are confusing unpredictability with indeterminism. In other words, they think that since they don’t know what will happen, future events haven’t been determined yet. However, this isn’t necessarily true.

For example, imagine shuffling a deck of cards and drawing the top card. That event is unpredictable because you don’t know which card you’re going to draw, but it’s still predetermined because the order of cards was fixed as soon as you stopped shuffling. To look at it another way, only one card could possibly be on top of the deck (as determined by how you shuffled it)—you just don’t know which card that is. Tying this example back to human behavior, Sapolsky would say that a human can’t decide to do something other than what is predetermined, the same way that a deck of cards can’t decide to change which card is on top.

Secondly, this argument implies that being unable to link cause with effect means there is no cause. So, if you don’t know why someone did something, then there must not have been a definitive reason for their action—they simply chose to do it. Sapolsky retorts that this misinterprets a fundamental point of chaoticism, which is that all events have definitive causes, but in many cases we’ll never be able to figure out what those causes were.

Theory #3: Emergent Complexity

The next concept Sapolsky discusses is emergent complexity: the idea that complex behaviors or properties can arise from the interactions between relatively simple things. For example, no single neuron has the ability to store information—however, when a lot of neurons communicate with each other in certain ways, we gain the ability to learn and remember things. Some people argue that, like memory, free will must be an emergent property of the brain.

Sapolsky’s argument against this theory is that emergent properties are often unexpected, but never impossible. Brain cells can’t simply activate themselves without any stimulus, meaning they can’t create thoughts and decisions that are free of external influences.

Theory #4: Quantum Indeterminacy

So far we’ve been discussing the behavior of objects that are relatively large by the standards of physics. For this final theory, Sapolsky delves into subatomic particles like electrons and quarks, which—for reasons that even the world’s top physicists don’t yet understand—behave according to completely different rules from larger objects. Some people believe that those rules, collectively called quantum mechanics, make free will possible.

Most relevant to this discussion is the principle of quantum indeterminacy, which states that a subatomic particle’s behavior at any given moment is not the result of what happened the moment before. Scientists have observed this in numerous experiments with subatomic particles; identical starting conditions can produce different results, which overturns a fundamental point of determinism.

Therefore, it seems that subatomic particles aren’t bound by the same deterministic laws that larger objects are. So, the argument goes, could it be said that those particles are choosing how to behave? And doesn’t that suggest that people—who are, after all, made of such subatomic particles—might be able to do the same?

Arguments Against Free Will Via Quantum Indeterminacy

As with the other theories we’ve discussed, Sapolsky has several arguments against the idea that quantum indeterminacy makes free will possible.

The first flaw in this theory is right in the name: The particles’ behavior is indeterminate. This means their actions aren’t being controlled (which is to say, determined) by any other force, including the force of will. So, even if quantum mechanics do allow for multiple courses of action arising from the same starting point, it still wouldn’t be you choosing which course to take.

This brings us to the second problem: Quantum indeterminacy is random. Scientists know this because while they can’t predict exactly how subatomic particles will behave, in some experiments they’ve been able to predict how likely each possible outcome is. Therefore, if your free will were fueled by quantum indeterminacy then your actions would also be random, and that’s obviously not the case.

To illustrate the point, you can compare the randomness of subatomic particles to the randomness of rolling dice. For instance, if you roll two six-sided dice, there’s no way of predicting exactly what total you’ll get—but you can calculate the odds of each result fairly easily. However, human behavior is much too focused and purposeful to be the result of subatomic dice rolls.

Finally, Sapolsky explains that quantum indeterminacy cancels itself out on the macroscopic scale (anything big enough to see with the naked eye). This is because there are an incredible number of indeterminate quantum events happening at any given time, so they all average out; for each particle that randomly moves, another particle randomly moves in the opposite direction, and the net impact of those movements becomes zero. It’s incredibly unlikely that enough particles would randomly behave the same way to influence even a single one of your neurons, never mind controlling your entire brain for your whole life.

Implications of a World Without Free Will

Now that we’ve reviewed Sapolsky’s arguments against the possibility of free will, we’ll discuss why this issue matters. There are enormous psychological and societal implications to a universe without free will, but the author argues that embracing determinism would be largely positive for society.

We’ll begin this section by explaining what it would be like to live in a world where people aren’t praised or rewarded for their achievements (because those achievements weren’t the result of their decisions). Next, we’ll examine the implications of a world where people aren’t blamed or punished for their actions. Finally, we’ll discuss why Sapolsky believes that such a world would be fairer and kinder than our current individualistic society.

Implication #1: No Praise or Rewards

As we’ve already discussed at length, if free will doesn’t exist, then by definition people aren’t responsible for their own actions. Sapolsky says that, if we follow that line of thought to its conclusion, it suggests that people shouldn’t be praised or rewarded for the things they accomplish. However, he also recognizes that this goes against human nature in several crucial ways:

1) It goes against our natural drive to compete. This doesn’t just mean our drive to prove that we’re better than our peers, but also our ancient drive to compete for resources. Why do anything if we won’t be rewarded for it? For instance, why enter a competition if there’s no trophy to win? Why go to work if we won’t get paid? Again, what’s the point of doing anything?

2) It goes against our natural desire for recognition. We want our efforts to be recognized and our accomplishments to be praised. If nobody’s going to be proud of us—including ourselves—then what’s the point of achieving anything?

3) It goes against our natural need for control. We like to believe, and centuries’ worth of culture have taught us, that we can take control of our lives through discipline and hard work. Therefore, we naturally resist the idea that we’re not in control and never can be. It’s hard to accept that all of our hard work and everything we’ve achieved are just our winnings from some cosmic lottery.

The Point: The Common Good

As you’ve just seen, a common concern about a deterministic world is that there seems to be no point to doing anything, since you won’t get recognition or rewards for what you accomplish. In response, Sapolsky offers two reasons why your efforts would still be worthwhile: a selfish motivation and a selfless one.

From a selfish perspective, anything that improves the world around you will also make your own life better. For example, working to keep your neighborhood clean would improve your quality of life, even if nobody personally thanks you for it.

From a selfless perspective, Sapolsky argues that if you’re concerned about praise and rewards in the first place, then you’re almost certainly coming from a position of relative privilege. This is because people who have to scrabble for basic necessities like food and shelter don’t have the luxury of worrying about such things.

Therefore, the author urges you to improve the world, not for your own benefit, but for the benefit of people who are less fortunate than you.

Implication #2: No Blame or Punishment

While many people won’t want to give up on getting rewarded for what they do, Sapolsky says that the opposite side of this issue (giving up on blaming and punishing people for wrongdoing) will also spark fierce resistance. One major reason people will cling to the idea of accountability is that human brains are hardwired to search for answers. This is to say, we naturally want to know why something happened and what we should do about it.

Unfortunately, we also tend to look for answers that are simple and satisfying. So, when something bad happens, we start asking simple questions: who’s to blame (why it happened) and how we should punish them (what we’re going to do about it). Compounding this issue is the fact that, in many cases, it seems obvious that a person is responsible for what happened, and seeing them punished satisfies our sense of justice.

For example, if your car is stopped at a red light and someone rear-ends you, of course you’re going to want to blame that other driver for the accident and demand that they pay for any damages. Determinism says that the crash was the inevitable result of myriad different factors, and therefore the other driver isn’t responsible. Unfortunately, that answer is both complicated and unsatisfying, so your mind is likely to resist it.

With all of this said, Sapolsky gives a partial counterpoint to himself: Rewards and punishments would still make sense to the extent that they can influence people’s behavior. For instance, if you punish a child for breaking something, that child will probably be more careful in the future—it isn’t fair, but it’s effective nonetheless.

Corollary: A Rehabilitation-Focused Mindset

One major concern about a world without free will is that it would be a world without accountability. After all, if criminals’ actions aren’t their own fault, then don’t we have to simply let them go free to commit more crimes? However, Sapolsky argues that’s only true if the purpose of the legal system is to punish criminals. Instead, he says, its purpose should be to protect society and work for the common good.

With that shift in mindset it would still be possible to imprison criminals because doing so protects other people and upholds order in society—there’s no need to believe that people choose to commit crimes and should be punished for it. However, Sapolsky adds that the focus of imprisonment would have to change from punishment to rehabilitation: giving people the skills, resources, and (if necessary) treatment to do better after they’re released.

As before, drawing a parallel to computers can help to illustrate this point. When a programmer realizes that their program isn’t acting the way it was intended to, they simply patch the code to eliminate that problem. Rehabilitation is like a software patch for people.

On the other hand, it would be absurd for a programmer to just put a glitchy program into a locked folder and hope it decides to change its behavior. Such an approach could never work because the problem is in the software’s programming, not its “choices.” And yet, that’s exactly what the legal system does by imprisoning people.

Implication #3: A Kinder, Fairer Society

Finally, Sapolsky argues that—if we accept that free will doesn’t exist and we accept the implication that people can’t be held accountable—the rational conclusion is that we must create a more equitable society. This is because determinism eliminates the question of what people “deserve.”

The author reasons that, if people’s lives are predetermined, then pure chance is the only difference between the richest person on Earth and a homeless person; it all comes down to who each person happened to be born as. Therefore, the wealthy don’t deserve their success and the poor don’t deserve their hardship, meaning that the inequality in the world today is monstrously unjust. Accepting that people aren’t responsible for their own situations also means accepting that we should correct this imbalance as much as possible.

Why Determinism Demands Kindness and Understanding

Sapolsky points out that determinism has major implications for how we treat each other on a personal level, not just a societal one. It means accepting that even people who seem detestable don’t deserve to be treated badly, and we should therefore meet everyone with as much kindness and understanding as we can muster.

For instance, we’d have to recognize that abusive spouses aren’t at fault for the conditioning or psychological disorders that lead them to believe their actions are acceptable. However, as we discussed before, understanding that people aren’t in control of their actions doesn’t mean letting them go unchecked—anyone who’s a danger to others would need to be arrested and rehabilitated to protect the common good. However, accepting determinism does mean letting go of satisfying urges like hatred and the desire to see “bad” people suffer.

Sapolsky points out that this goal may not be as impossible as it seems. Civilization has already made large strides toward humane treatment for criminals and outcasts. For instance, public torture and execution are no longer accepted forms of punishment in most cultures, and people are generally still satisfied as long as they know that criminals are going to prison. Therefore, it’s reasonable to think that the public can also adjust to the idea of “bad” people going to places that can help them instead of punishing them.

Conclusion: Act “As If”

Sapolsky concludes by saying that, while all available evidence suggests people’s actions are predetermined, it’s impossible to know for sure. However, he argues that it would be best for people to assume that free will doesn’t exist. This is not only because there’s no evidence for the existence of free will, but also because of all the ways that such a worldview would improve society, as we discussed before.

Sapolsky adds that this puts him in a similar position to many philosophers throughout history; they, like him, usually ended up admitting that it’s impossible to prove whether or not people have free will. However, unlike him, most of those philosophers believed it would be better for people’s mental and emotional health to assume that free will exists, so they concluded that it’s rational to keep believing in it.

If the human race has spent millennia believing in free will without any proof, Sapolsky argues, then we don’t need conclusive proof to overturn that belief, especially when doing so would have so many benefits. Therefore—even if the evidence and logic he’s presented throughout Determined haven’t fully convinced you—he urges you to act as if the absence of free will is a proven fact and adjust your worldview accordingly.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Robert Sapolsky's "Determined" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Determined summary:

- Why some people believe we have free will—and others don’t

- Three implications of a world without free will

- Why we should live as though free will doesn’t exist (even if it does)