This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Why We Get Sick" by Randolph Nesse and George Williams. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

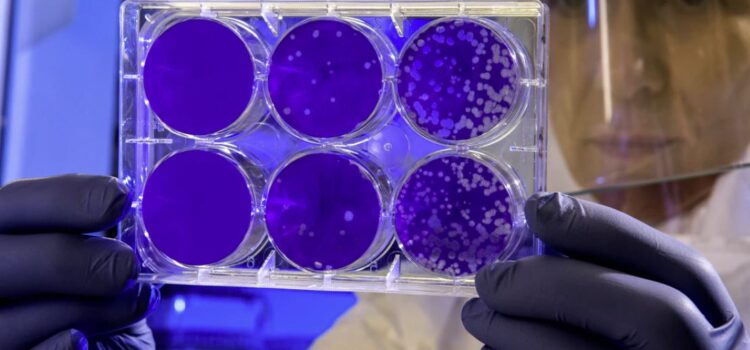

How does the human body defend against pathogens and bacteria? What strategies and counters do the body use?

Some bodily defense mechanisms have dual purposes that benefit both the host and the pathogen. Similarly, some infectious diseases cause damage to the host which is costly to the pathogen as well. This is because both the host and the pathogen need to make compromises.

Keep reading to learn about the body’s defense against pathogens and bacteria.

Nuances of the Body’s Defense System Against Pathogens

Less accessible body areas have less regenerative capability. Infections of the brain or heart are usually fatal, so maintaining regenerative capabilities in these areas would have little benefit. As a result, natural selection seems to have shown that defense against pathogens and bacteria to protect the brain during the rare infection don’t outweigh the costs of maintaining this system.

Some defensive behaviors have dual purposes, benefiting both host and pathogen.

- Sneezing and diarrhea may be a defensive mechanism, but it also helps spread the pathogen.

- Ideally, in medicine, we fine-tune defense to net benefit the human host.

Sometimes, infectious disease really does cause damage to the host. Often this is done to procure more resources for the pathogen and support its spreading or reproduction. Beyond these purposes, damage to the host is often incidental and costly to both host and pathogen. It does no good for the tapeworm to cause its host to be malnourished; it does no good for hepatitis to destroy the liver completely and quickly kill the host. Any especially virulent strain that rapidly killed its host would have little chance to spread itself, and the mutations that caused its virulence would be selected against.

Pathogens Adapt to Hosts

Just like animals, bacteria and viruses undergo natural selection to propagate their genes. The pathogens that can best overcome host defenses succeed in reproducing and spread their beneficial genes to the population.

Pathogens have evolved a variety of responses to host defense, including:

- Imitating the host immune system.

- Streptococcus bacterium presents a surface so similar to human cells that the immune system has difficulty recognizing it. In fact, antibodies produced in response to strep can damage the host itself, causing rheumatic fever and even mental disease like Sydenham’s chorea and possibly obsessive-compulsive disorder.

- Evading the immune system.

- The parasite that causes African sleeping sickness changes its surface proteins constantly to evade detection by antibodies. This is like a spy constantly changing its disguise.

- Manipulating the host.

- The rabies virus moves to the brain and adjusts the host behavior to better increase its own propagation. It paralyzes swallowing muscles, causing saliva to build up in the mouth and thus increasing the concentration of virus in the mouth. Then it increases the host’s aggression to better spread by bite.

Strategies and Counters

We’ve seen a variety of strategies for hosts and counterstrategies by pathogens. Some observations of infectious disease, like decreasing iron levels, benefit the host; others benefit the pathogen; some are merely incidental damage in the ongoing war.

Here is a classification of how infectious disease manifests, based on their function.

| Observation | Examples | Beneficiary |

| Hygienic measure by host | Killing mosquitoes, avoiding sick neighbors, grooming, removal of parasites | Host |

| Host defenses | Fever, iron withholding, sneezing, vomiting | Host |

| Repair of damage by host | Regeneration of tissues | Host |

| Compensation for damage by host | Chewing on the other side of the mouth to avoid tooth pain from infected tooth | Host |

| Damage to host tissues by pathogen | Tooth decay, hepatitis liver damage | Neither |

| Impairment of host by pathogen | Ineffective chewing, decreased detoxification of blood by infected hepatitis liver | Neither |

| Evasion of host defenses by pathogen | Molecular mimicry (MHC complex), change in antigens (trypanosome changes surface proteins) | Pathogen |

| Attack on host defenses by pathogen | Destruction of white blood cells; secretion of factors that inhibit inflammation | Pathogen |

| Uptake and use of nutrients by pathogen | Growth and proliferation of trypanosomes, viruses bind to cellular receptors and enter cells to hijack resources and replicate | Pathogen |

| Dispersal of pathogen | Transfer of malaria parasite to a new host by mosquito, sneezing | Pathogen |

| Manipulation of host by pathogen | Exaggerated sneezing, diarrhea, behavioral changes (rabies increases chance of bites) | Pathogen |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Randolph Nesse and George Williams's "Why We Get Sick" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Why We Get Sick summary :

- Why evolution hasn't rid humans of all diseases

- How reproductive fitness is more important than overall survival

- How you evolved to dislike the sound of a baby crying