This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Unsettled" by Steven E. Koonin. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

How much is the Earth warming? What’s the cause? What does the future hold?

With all of the information about climate change available at your fingertips, you probably still have unanswered questions. In Unsettled, former energy industry scientist Steven E. Koonin provides his answers to three of the biggest questions in the conversation.

Continue reading for three climate change questions and answers from Koonin.

3 Climate Change Questions and Answers

Koonin served as the former chief scientist for the British oil and gas company BP, where he focused on renewable energy, and was undersecretary for science in the Obama administration, so he brings years of scientific experience into his discussion of climate science.

Let’s take a look at these three major climate change questions and answers from Koonin’s book:

- How much has the climate warmed recently?

- How much are humans responsible for that warming?

- How accurately can we predict future climate change?

As we’ll see, though Koonin’s answer to the first question aligns with the scientific mainstream, his answers to the second and third questions both depart from the mainstream.

Question #1: How Much Has the Climate Warmed Recently?

Before assessing human impact on global warming, scientists naturally ask about the extent of global warming itself. In this respect, Koonin agrees with the scientific consensus: The Earth’s average surface temperature has risen by about 1°C (1.8°F) since 1850, with a particularly sharp increase beginning in 1980.

To understand climate data, however, Koonin asserts that we need to understand what “climate” means in the first place. Although many laypeople conflate climate with weather, Koonin defines climate as a region’s average weather across a long period of time—typically 30 years. This means we can only see climate change over longer timespans because variations in shorter timespans might not affect a region’s average weather in the long term.

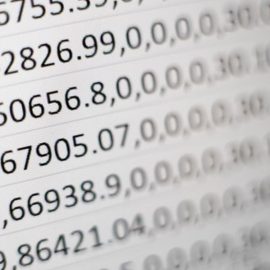

In light of this definition, Koonin examines scientific findings showing the average surface temperature anomalies from 1850 to 2020. These anomalies are differences in the globe’s temperature from its average temperature over a longer term. For example, if a region’s average temperature from 1900 to 2000 was 5°C, and its average temperature in 1960 was 5.4°C, then 1960 represents a temperature anomaly of 0.4°C.

Average surface temperature anomalies rose 1.1°C (2°F) globally between 1900 and 2020, a rate of about 0.09°C (0.16°F) per decade. So, Koonin grants that the temperature has risen globally since 1900. However, Koonin points out two further important patterns: First, although the graph shows a clear long-term trend, it fluctuates dramatically in short-term intervals. Because of this fluctuation, Koonin notes that changes over a few years don’t necessarily amount to climate change.

Second, the rate of temperature increase wasn’t uniform across 120 years—indeed, from 1940 to 1980, temperatures actually decreased an average of 0.05°C (0.09°F) per decade. As we’ll see in later sections, Koonin argues that this complicates the narrative that human influences have consistently led to warmer temperatures.

Question #2: How Much Are Humans Responsible for Recent Warming?

While Koonin agrees with the mainstream view about the extent of recent global warming, he disagrees when it comes to the cause of this recent warming. In particular, he contends that the scientific evidence doesn’t conclusively establish the extent of our influence, though best estimates suggest it’s relatively small.

To defend this assertion, Koonin points out that the Earth has historically experienced significant changes in average surface temperature anomalies. For example, the last million years have featured cycles of quick warming followed by gradual cooling. So, the causes must have been natural because the cycles occurred long before humans began impacting the climate.

Consequently, Koonin infers that we can’t rule out the possibility that recent warming is also partially due to natural causes. At the very least, he argues we must carefully consider the evidence to see whether—or to what extent—we’ve contributed to rising temperatures.

Koonin suggests that, when we do so, we’ll find that our impact on the climate is relatively small. To show as much, he analyzes this impact in two ways: 1) the extent to which we’ve caused the climate to warm by increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and 2) the extent to which we’ve caused it to cool by inserting reflective aerosols into the atmosphere.

Question #3: How Accurately Can We Predict Future Warming?

In addition to differing from mainstream climate science about the extent of humans’ impact on the climate, Koonin also differs on the accuracy of climate models. Specifically, Koonin argues that climate scientists’ models don’t reliably predict future climate change, because they have three flaws: The grids they use are too large; they require initial conditions that we can’t measure; and they have to be “tuned” to avoid contradictions.

Flaw #1: Grid Sizes

First, Koonin argues that climate models’ grids are too large to account for smaller climate phenomena, which makes them less accurate. These models, he clarifies, plot the earth’s atmosphere on a grid composed of 100-kilometer by 100-kilometer sections, with every section reporting an array of measurements—temperature, humidity, wind speed, and so on.

As such, Koonin claims these grids can’t account for weather-related phenomena that occur on scales smaller than 100 kilometers, such as storms and cloud coverage. Consequently, these models must accept some degree of inaccuracy.

Flaw #2: The Problem of Initialization

Moreover, Koonin argues that these models require data about initial weather conditions that we often don’t have access to. In particular, he argues that we lack the observational apparatus needed to supply such in-depth information for the entire globe. In turn, models depend on assumptions for many grid segments that aren’t empirically verified, making them less credible.

Flaw #3: The Tuning Process

Finally, Koonin notes that climate scientists “tune” their models to account for incorrect results, which makes them suspect. Because climate models are inaccurate initially, due to the complexity of the climate system and the array of subgrid assumptions that must be made, climate scientists tune them to avoid inconsistent and inaccurate predictions. According to Koonin, however, this process makes climate models far less credible, as their creators change crucial parameters by fiat to make the models appear more accurate.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Steven E. Koonin's "Unsettled" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Unsettled summary:

- That humans are only partially to blame for the warming climate

- Why the proposed solutions to climate change are unlikely to succeed

- Alternative responses to climate change and how to improve understanding