This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Checklist Manifesto" by Atul Gawande. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

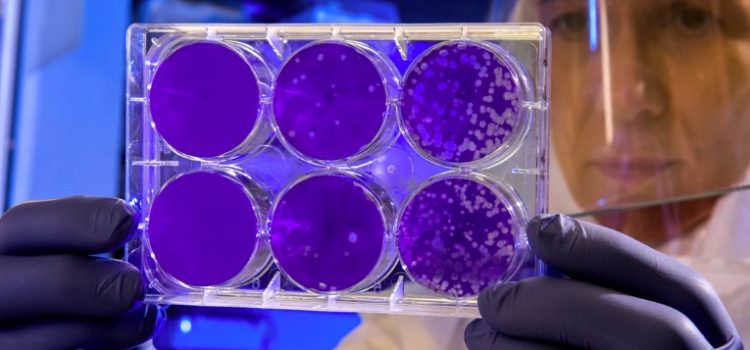

In 2001, a critical care specialist at Johns Hopkins Hospital, Peter Pronovost, decided to try a checklist for doctors, targeting a common problem in ICUs: central line infections. How could the hospital improve central line-associated bloodstream infection (CLABI) prevention?

We’ll cover Pronovost’s simple technique for CLABI prevention and look at its success throughout the nation.

The CLABI Prevention Checklist

A central line is a type of catheter placed in a large vein that allows multiple IV fluids to be given and blood to be drawn. Central line infection prevention is key. Pronovost’s checklist listed the steps for avoiding infections:

- Wash your hands with soap.

- Clean the patient’s skin with antiseptic.

- Put a sterile drape over the patient.

- Wear a mask, hat, sterile gown, and gloves.

- Put a sterile dressing over the insertion line.

He asked nurses to watch doctors put lines in patients for a month and note and how often they carried out each step. More than a third of the time, doctors skipped at least one step. He then enlisted the hospital administration to authorize nurses to stop doctors if they skipped a step on the CLABI prevention checklist.

Over a year, the line infection rate dropped from 11 percent to zero. Over 15 more months, there were only two line infections. Pronovost calculated that at just a single hospital, the CLABI prevention checklist had prevented 43 infections and eight deaths and saved $2 million.

Building on the Success of the CLABI Prevention Checklist

Pronovost tested more checklists in the Johns Hopkins ICU. For instance, his team created a checklist to ensure nurses checked patients for pain at least once every four hours and provided medication if necessary. The number of patients suffering untreated pain dropped from 41 percent to 3 percent.

They created another checklist for patients on mechanical ventilation or breathing assistance. Steps included making sure they received an antacid and propping up the head of the bed. The proportion of patients not receiving the specified care fell from 70 percent to 4 percent, incidence of pneumonias dropped by a quarter, and 21 fewer patients died than in the previous year.

Pronovost’s teams also found that care improved when they had doctors and nurses in the ICU create their own checklists for what should be done. The average length of stay in the ICU declined by half.

These checklists helped jog their memory and established the importance of basic steps, which even experienced staff had overlooked. They also set a higher standard for performance. For instance, before the ventilator checklist was implemented, half of the ICU staff hadn’t realized the importance of giving patients antacid medication.

Statewide Implementation of CLABI Prevention Checklists

In 2003, Michigan Health and Hospital Association implemented Pronovost’s CLABI prevention checklist throughout the state’s ICUs; it became known as the Keystone Initiative.

As part of the implementation process of CLABI prevention, each hospital assigned a senior hospital executive to hear staff concerns and help to solve problems. Executives learned that the right soap, shown to reduce line infections, wasn’t available in more than two-thirds of ICUs. They quickly provided the soap to all Michigan ICUs. Other important supplies that were often unavailable were provided as well.

In 2006, the Keystone Initiative published its findings about CLABI prevention in a landmark article in the New England Journal of Medicine. Within the first three months of using the checklist, the central line infection rate dropped by 66 percent. In terms of infection rates, the average ICU in Michigan did better than 90 percent of ICUs nationwide. In the first eighteen months, hospitals saved an estimated $175 million and more than 1,500 lives.

The key problem and solution in CLABI prevention were simple:

To reduce central line infections, maintain sterility.

All could be resolved by using a simple tool to compel the needed behavior — a checklist. We’re constantly confronted with similar simple problems that can be mitigated by checklists — for instance, a nurse’s failure to wear a mask while putting in a central line or a surgeon’s failure to recall that one cause of a cardiac arrest could be a potassium overdose.

But can checklists be used to address complicated or complex problems, such as ICU work, where there are many tasks performed by multiple people, dealing with individual patients with individual and complex problems? Medicine encompasses all three types of problems — simple, complicated, and complex. It’s important to get basic things right, while allowing skill, judgment, and ability to react to the unexpected.

The medical profession could learn from the construction industry, which handles the design and construction of huge and complicated structures with the help of sophisticated checklists addressing the full range of problems.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Checklist Manifesto" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Checklist Manifesto summary :

- How checklists save millions of lives in healthcare and flights

- The two types of checklists that matter

- How to create your own revolutionary checklist