This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" by Joseph Campbell. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

How does Buddha’s journey toward enlightenment follow the hero’s journey, as described in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces? What was the Buddha’s “call to action”?

In Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey, every significant adventure in mythology and religion starts with a call to action. We’ll cover how the Buddha’s journey conforms to the hero’s journey and what the Buddha’s call to action was.

Buddha’s Journey as Hero’s Journey

The archetypal myth is that of the hero’s journey, which details the exploits of an exalted figure such as a legendary warrior or king. But the hero can also start out as an obscure figure of humble origins, on the fringes of society. Frequently, this hero is born to lowly circumstances in a remote corner of the world and is the product of immaculate conception and virgin birth. Thus, they start out with some essential element of the gods already inside them. The Buddha’s journey is an example of a well-known hero’s journey (although the Buddha’s journey doesn’t start with a hero born to lowly circumstances).

The hero sets out on a journey to acquire some object or attain some sort of divine wisdom. This can be something material (like Arthur’s quest for the Holy Grail) or something with far greater spiritual weight (like the Buddha’s journey to find ultimate enlightenment). The hero undergoes great trials and tribulations during the course of their quest, undergoes a spiritual (and sometimes literal) death and rebirth, and transforms into an entirely new being. They gain new powers, and with those powers, achieve their goal—they receive the ultimate boon. They then return home to share this heavenly reward with their people—and in doing so, redeem all mankind.

The Composite Hero

The heroes of mythology, whether it’s King Arthur, Odysseus, the Buddha, the Chinese emperor Huang Ti, or Moses, share similar characteristics.

They are often figures who have unique talents or gifts and hold an exalted position within their society—they are renowned scholars, warriors, or kings. But the opposite can also be true: the archetypal, or composite hero can also start out as an obscure figure of humble origins, on the fringes of society. But whether they start out as prince or pauper, they set out on their journey to address some sort of need, to fill some kind of spiritual void. In simple romance tales or fairy tales, this can be nothing more than obtaining a golden ring or the hand of the fair princess, while in myths with deeper theological undertones (like the story of Christ), the hero sets out to redeem and renew the spiritual life of the entire world and save it from falling into ruin.

The Mythological Template

Although the settings and plots of myths vary widely across time and space, from the Homeric poems of ancient Greece to the enlightenment of the Buddha’s journey in India to the Christian story of the birth and resurrection of Christ, they all share a certain core set of themes, a standard template. This template is the mythological adventure of the hero—someone who sets out on a journey, often with the help of a sage guide and allies along the way, overcomes obstacles, and achieves some sort of transformation which he or she then shares with the world. This can either be the sharing of a literal bounty (bringing abundance and prosperity back to a hungry and impoverished community) or a deeper, more spiritual redemption of a wayward and fallen people.

The point in space and time where divine wisdom is imparted to the physical world is known as the World Navel. It is the center of the universe, the spot from which all life grows: it is the portal between our world and the world of the divine. It is represented in a variety of ways across religious and mythological traditions and throughout time—it is Rome in Catholicism, Mecca in Islam, or the Immovable Spot in the legend of the Buddha’s journey—but the idea is always the same.

This transformation of the hero comes from tapping into a source of deep spiritual wisdom, which is often revealed to have been within the soul or psyche of the hero from the beginning. Thus, the archetypal hero’s journey involves a spiritual awakening, an attainment of some piece of the gods.

The essential feature, the basic common denominator of mythology, is the monomyth. It is the core structure of the myths, the journey that all heroes must undergo. It involves three rites of passage—separation, initiation, return. From the myths of the ancient Egyptians and the medieval Arthurian legend to the folk-tales of the native Maoris of New Zealand, the pattern of the hero’s journey usually follows this cycle: a separation from the world he or she has always known (embarking on the quest), gaining some spiritual or other-worldly power, and a return in which they share the boon of the new power with humanity.

Let’s discuss the example of the Buddha’s journey to illustrate the pattern.

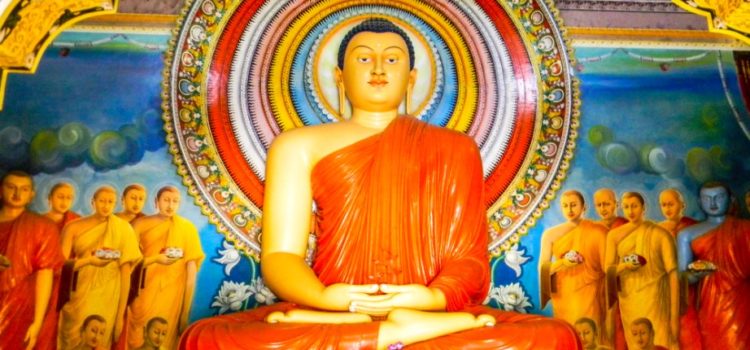

The Struggle of the Buddha‘s Journey

In the story of the Struggle of the Buddha, the founding story of Buddhism, we see all three elements of the monomyth. First, we see separation. The prince Gautama Sakyamuni (also known as Siddartha Gautama and the Future Buddha) escapes his ancestral home and cuts off his royal locks. He assumes the costume of a monk, wandering through the world and living a life of extreme austerity and asceticism. During this time, he transcends to the eight stages of meditation. This is the first basic stage of the Buddha’s journey and the hero’s journey.

Next, we witness initiation. One day, he tosses an empty bowl into a river, and sees that the bowl flows upstream. This is the signal that his time of ultimate enlightenment is near at hand. He journeys to the Tree of Enlightenment, where he meets Kama-Mara, the god of love and death. Kama-Mara attempts to dislodge him from the tree, deploying all manner of fearsome monsters and deities at Gautama. But in repelling all of Mara’s onslaughts, the Future Buddha acquires knowledge of his previous existences, the power of omniscience, and a divine understanding of the chain of causation. He becomes Buddha, “The Enlightened One.” This is the second basic stage of the Buddha’s journey and the hero’s journey.

Finally, we see return. After this victory, Buddha initially despairs of being able to communicate his message. But the god Brahma dissuades him from this pessimism and urges him to teach gods and men the path of enlightenment. Thus, Buddha returns to the cities and the hustle and bustle of the world from which he had originally come to share the gift of his knowledge and wisdom with the world. This is the third basic stage of the Buddha’s journey and the hero’s journey.

The Buddha’s Journey and the Call to Adventure

In the first part of the monomyth, we meet our hero, our “man of destiny,” and witness their call to adventure. The call to adventure can come about through chance, even a mistake or blunder, which introduces the hero to a hidden world of possibility, guided by mysterious forces which the hero will come to understand through the course of their journey. We can see this element of the hero’s journey in the story of the Buddha’s journey.

Future Buddha and the Old Man

If we revisit the story of the Buddha’s journey, we see one of the world’s most famous calls to action. The young prince Gautama Sakyamuni (Future Buddha) has been shielded from all knowledge of age, sickness, and death since the time of his birth—the father wants his son to assume the duties of the kingdom and not to be distracted by lofty spiritual or philosophical ideas. He wants the prince’s mind to be squarely on the concerns and experiences of the physical world, even granting him three palaces and thousands of concubines to keep his focus on secular matters.

The gods realize that the time has now come for the Future Buddha to begin his enlightenment, so they decide to send him a sign. One day, the prince ventures out and encounters the gods in the form of a decrepit old man, something he’d never been allowed to see before. He returns home, distraught after learning that everyone and everything that lives must eventually grow old. He has the same reaction upon seeing the gods in the form of a sick man one day and a dead man the next. Each time, the king increases the security around his son, trying to censor what he sees.

Finally, one day, the prince sees a well-dressed monk, created and placed there by the gods. The prince’s charioteer tells him that this is someone who has retired from the world. The prince is intrigued by the idea of following this man’s example. Thus, the seeds have been planted for the prince’s spiritual journey and his ultimate transformation—his death and rebirth as the Future Buddha.

The Buddha’s Journey: Return

After the completion of the quest, the hero must return home with their bounty, be it Jason’s Golden Fleece, or the Little Briar Rose of German legend. The final piece of the monomyth now requires the hero to share this wisdom, this hard-won prize back to the real world, where it will benefit the hero’s community, and, possibly, the universe.

Refusing the Return

But sometimes, mythology records a hero unwilling to return to the world. Just as they may have refused the initial call to adventure, so they may refuse their duty to return home and bestow their newfound wisdom upon the rest of humanity. Even the Buddha, after his victory at the Tree of Enlightenment, doubted if it was even possible to bring the joy of true enlightenment to other mortals. It is tempting for the hero to simply turn away from the world and reside forever in Paradise.

Mythology is still relevant. It binds us closer and provide us with a shared sense of community. Though we may lead atomized lives as husbands, wives, sons, daughters, professionals, and members of this or that nationality, we are bound together through shared myths. The ceremonies that derive from mythology, those of birth, initiation, marriage and death, remind us that we are part of something much larger than ourselves. We are only a cell, an organ of a much larger being. This is as true for us as it was for the ancients. Like Odysseus, like the Buddha, like Cuchulainn, great marvels and unfathomable transformations await the modern hero who heeds the mythic call.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Hero with a Thousand Faces" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Hero with a Thousand Faces summary :

- How the Hero's Journey reappears hundreds of times in different cultures and ages

- How we attach our psychology to heroes, and how they help embolden us in our lives

- Why stories and mythology are so important, even in today's world