This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Killers of the Flower Moon" by David Grann. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What was the motive of the Osage murders? Was justice ultimately done? How did the case shape the future of law enforcement?

David Grann’s book Killers of the Flower Moon explores the Osage Reign of Terror. This was a series of organized killings of members of the Osage Indian tribe that took place in Osage County, Oklahoma, during the 1920s.

Continue reading for an overview of this sad but important book.

Overview of the Book Killers of the Flower Moon

Throughout a five-year period of mayhem and slaughter running from approximately 1921 to 1926, prominent members of the community conspired to murder their Osage neighbors—men, women, and children. David Grann relates this grim story in his book Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI.

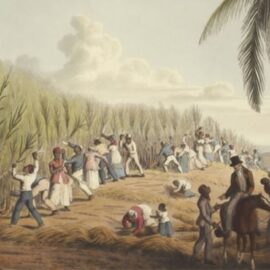

The motive for these murders was profit—specifically the oil wealth of the Osage, which they had come into when oil was discovered on their reservation in the late 19th century. Whites in Oklahoma had long schemed to expropriate and defraud the Osage out of their money, largely through a legally mandated system under which individual Osage would be declared financially “incompetent” and court-appointed white guardians installed to oversee their assets. These guardianships offered unbounded opportunities for graft and embezzlement—in many ways, the murderous campaign of the 1920s was merely the logical extension of this long history of exploitation.

The murders were also the catalyst for a major reformation of American law enforcement. The Bureau of Investigation (the predecessor agency of the FBI) and its fiercely ambitious director, J. Edgar Hoover, used the high-profile Osage case to assert the role of the federal government in the world of local law enforcement on an unprecedented level. In doing so, Hoover made great publicity of the Bureau’s exploits and forever reshaped the image of law enforcement in the American popular imagination—away from the old romantic ideal of untrained frontier lawmen and amateur local sheriffs, and toward his vision of sober, rational, scientific, and procedural G-Men.

Financial and Cultural Exploitation

In the late 19th century, oil had been discovered on the tribal reservation of the Osage people, who lived primarily in Osage County, Oklahoma. The tribe had suffered the loss of its tribal lands and been decimated by both smallpox epidemics and military defeats by the United States throughout much of the century. But, overnight, the oil discovery turned the tribe into one of the wealthiest per-capita groups in the world, with the total tribal income from leases to the oil companies running into the tens of millions and leases on individual tracts climbing as high as $2 million.

To manage this influx of money, the Osage tribal leadership instituted a headright system, under which each member of the tribe was entitled to annual royalties from the oil production, distributed in equal measure to members of the tribe. Although individuals could sell their surface land, they could not buy or sell headrights—these could only change hands through inheritance. This system was meant to ensure tribal control of the oil wealth in perpetuity.

The wealth of the Osage, however, attracted the jealousy and greed of whites in Oklahoma. These attitudes would soon be given the force of law. In 1921, Congress instituted a financial guardianship system, under which Osage were declared financially “incompetent” and unable to spend their own money as they saw fit. The rationale for this paternalistic policy was that the Osage were seen as childish, helpless people who could not be trusted to manage their own financial affairs. Left to their own devices, supporters of this policy argued, the Osage would squander their wealth on foolish and impulsive purchases. Worse, the decision to subject an Osage to the burden of guardianship was nearly always racially based—full-blooded members of the tribe were virtually guaranteed to have a guardian; those of mixed ancestry rarely were.

The courts appointed white guardians, usually drawn from the ranks of white attorneys, politicians, and bankers in the community, who would guard the Osage assets. This system kept the Osage in day-to-day poverty, despite being wealthy on paper—while providing ample opportunities for whites to embezzle and defraud them through a variety of schemes. By 1925, the government estimated that unscrupulous guardians had swindled the Osage out of $8 million.

The guardianship system was not the only way in which the paternalistic white authorities sought to “help” the Osage. In Oklahoma, the federal government ran a program of forced cultural assimilation. The ostensible goal of this program was to help integrate the Osage into mainstream American (i.e., white) society.

The real purpose, however, was to wipe out any traces of Osage religion and language—especially among children. Official government policy stipulated that native peoples like the Osage were morally and culturally unfit for self-government, and needed to be taught the ways of the white man in order to fully participate in American economic and political life. Thus, young Osage were forced to attend schools (often Christian parochial schools), where they would be taught to reject traditional Osage religion and culture, to be remade in the white man’s image.

These schools were English-only—children were not allowed to speak the language of their ancestors inside the walls of these harsh and forbidding institutions. By the early 1920s, speakers of the Osage tongue were dwindling, traditional modes of dress had all but disappeared, and most members of the tribe had converted to Christianity, with only faint vestiges of the old religion still observed.

The Failures of Local Law Enforcement

The five-year-long Reign of Terror began in May 1921 with the discovery of the body of a murdered Osage woman named Anna Brown. Anna had been married to a white man, as were her sisters, Mollie Burkhart and Rita Smith.

In these parts of rural Oklahoma in the 1920s, elements of the frontier justice system still remained. Police forces were not yet fully professionalized, so ordinary citizens still assumed some of the responsibilities of criminal justice, including the investigation of evidence and even the pursuit of suspects.

One of the remaining vestiges of this rough-and-tumble approach to criminal justice was the citizens inquest, in which members of the community would visit the scene of a homicide with the county coroner to collect evidence and record any witness testimony. Anna Brown’s inquest and on-the-scene autopsy were gruesome, hasty, unprofessional, unscientific, and amateurish even by the standards of the day, with no proper protocol or procedure followed and a crowd of onlookers (including Anna’s family) witnessing the whole grisly spectacle.

This was how law enforcement and criminal justice were still practiced in remote parts of the American West, even as late as the 1920s. Many rural sheriffs were not professionally trained law enforcement officials, but were instead rugged frontiersmen, so-called “lawmen” who were often corrupt, violent, and connected to criminal elements within their jurisdiction. Private investigators were not much better. Many agents of the famed Pinkerton Detective Agency were criminals themselves, with no respect for people’s civil liberties or proper protocol in criminal investigations. Many, similarly, used their position to extort and terrorize the very people they were meant to be protecting.

As the death toll rose and more Osage were killed, it became clear that state and local law enforcement was either too incompetent or corrupt to restore order and safety in Osage County. One special investigator or private detective after another would be found either taking bribes or participating in illicit criminal activities. To make things worse, red herrings and false leads repeatedly hampered the investigation, as the conspirators worked to manufacture evidence and throw the investigators off. By July 1921, the local authorities wrapped up the investigation, concluding that Anna Brown had been murdered by “parties unknown.”

The Bureau of Investigation Takes Over

More and more people were being found dead across Osage County, including the few white members of the community who had made genuine efforts to help the now panic-stricken Osage people. It was clear that the murders were the work of a well-organized and ruthless conspiracy.

In March 1923, Rita and Bill Smith (the sister and brother-in-law, respectively, of Mollie Burkhart) were killed when their house went up in an explosion. Mollie Burkhart was convinced that her family was being systematically eliminated and that she would be the next target. She was also getting sick, despite the treatment of local doctors who claimed to be giving her insulin for her diabetes. Mollie, in fact, wasn’t sick with diabetes—she was being slowly poisoned.

In the summer of 1925, the U.S. Justice Department decided that the federal government needed to take a more direct role in the Osage case, as most of the murders had taken place on federally controlled Indian land. The director of the Bureau of Investigation, now tasked with overseeing the investigation, was the fiercely ambitious and publicity-seeking J. Edgar Hoover. He saw in the Osage case an opportunity to transform his obscure federal agency (which was soon to become the famous and powerful FBI) into the new face of American law enforcement and massively increase his own power and influence.

Hoover appointed an agent named Tom White to head up the investigation in Oklahoma. White had a background as an old-style “lawman” and had never received any formal police training. A former Texas Ranger who had chased outlaws and robbers through the hills of West Texas, he seemed the very antithesis of Hoover’s ideal of the procedural, rational, scientific, and professional investigative agent.

Despite this background, White was actually a careful and methodical law enforcement agent who shunned violence and found rational inquiry to be a much better tool for apprehending criminals. Hoover selected him for the job because he knew White would be familiar with the kinds of unscrupulous characters he and his team of agents would meet in Oklahoma as they unpeeled the layers of the Osage murder case.

A Murderous Conspiracy

After arriving in Oklahoma, White and his handpicked team of agents had to pierce through a web of lies and deceit. Informants who appeared to be working to assist the investigation were revealed to be double agents who were feeding the Bureau misinformation and helping the conspirators get away with their crimes. The unreliability of sources, the reluctance of witnesses to come forward, and blatant corruption of local law enforcement officials made pursuing leads a bewildering exercise, especially once it became clear that the perpetrators were deliberately manufacturing evidence.

But White and his team were undaunted. Through a combination of undercover sleuthing, combing through financial records, and extracting confessions from key witnesses, the agents identified the businessman, power broker, and self-styled “True Friend of the Osage” William Hale as the mastermind behind the Reign of Terror. Hale had powerful business and political connections and supported the establishment of charities, schools, and hospitals for the Osage. Hale was more than just any local grandee, moreover—he was the uncle of Ernest Burkhart, Mollie Burkhart’s husband. He had been at Anna Brown’s funeral and even vowed to the family that he would seek justice for Anna.

The Bureau agents discovered that Ernest Burkhart and his brother, Bryan, had been willing and active accomplices in their uncle’s murderous conspiracy—Ernest Burkhart had been a party to the murder of his wife’s sisters. In piecing together the puzzle, White’s team saw that the motive for all the murders was simple: profit.

While individual Osage had been barred by the Tribal Council from buying or selling headrights, they could be inherited. An Osage who suffered many deaths in their family could find themselves with title to multiple headrights. As White studied the probate records dealing with the estates of murdered Osage, the outline of the murderous plot began to make sense.

Many of the headrights of the victims had been willed to Mollie Burkhart. When all of this money came to Mollie, it would be easy for Hale to exercise control of it through his easily manipulated nephew Ernest—though it would be even easier if Mollie were to be killed, too. This was why Mollie’s family was being systematically eliminated. Through oil headrights and life insurance policies, Hale and his conspirators had a direct financial stake in the deaths of many Osage.

Fighting for Justice

Building the case against Hale was difficult as, one after another, witnesses and co-conspirators who had participated in the plot kept dying under mysterious circumstances before they had the opportunity to cooperate with the investigation. Tom White knew he needed to act quickly to apprehend the perpetrators before Mollie Burkhart died of poisoning and the plot succeeded. Fortunately, Bureau agents arranged to have her moved to a hospital, where her condition began to improve once she was away from the machinations of her husband and his family.

In January 1926, White and his team decided to move forward with the testimony and evidence that they already had. The Justice Department handed down indictments for Ernest Burkhart and William Hale. U.S. Marshals arrested Ernest Burkhart, while Hale confidently and politely self-surrendered.

White knew that his case was shaky—much of it relied on the testimony of jailhouse snitches and known outlaws. If Hale’s lawyers were able to rebut the charges or if his influence and bribery succeeded in corrupting the trial, it would be a major source of embarrassment for the Bureau—one for which J. Edgar Hoover would hold Tom White responsible. But White bolstered his case by using the sworn testimony of another, unindicted co-conspirator, to extract a confession from Ernest Burkhart. Burkhart admitted his role in orchestrating the murders and helping his uncle manufacture false evidence.

Even with this, White faced daunting odds of convicting the conspirators. The Oklahoma state judicial system was wracked with corruption, and Hale would easily be able to manipulate it. White knew that white jurors would be especially reluctant to convict white defendants for murdering Osage Indians.

At the trial, Hale and his legal team transformed the proceedings into a circus. They told outrageous lies and blatantly attempted to tamper with and intimidate witnesses, including Ernest Burkhart, who, for a time, recanted his testimony and switched sides to become a witness for the defense. Tom White was outraged and appalled by the utter brazenness and arrogance of Hale’s conduct.

But when White was able to produce direct testimony from one of the men who, along with Ernest’s brother Bryan, had murdered Anna Brown, the defense began to collapse. Ernest Burkhart and William Hale were both found guilty. Hale was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

The Legacy of the Reign of Terror

In response to the murders, the Osage Tribal Council persuaded Congress to pass a law barring anyone who was not at least half-Osage from inheriting a headright, removing some of the incentives for whites to murder them. Anna divorced Ernest shortly after he was sent to prison, revolted and outraged by what he and his family had done to her loved ones. She remarried and was restored to full financial competence (freeing her from the corrupt guardianship system), before passing away in 1937.

Tom White became the warden of the U.S. penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, where he was known for his relatively humane treatment of inmates and support for a more rehabilitative approach to criminal justice. In 1931, he was shot in the arm by a gang of inmates attempting to escape. Although he survived, he permanently lost the use of his left arm. After retiring in 1951, White attempted to publicize his role in cracking the Osage case but was coolly rebuffed by the self-aggrandizing Hoover, who had little use for his former star agent. After failing to find a publisher for his memoirs, White died in 1971, an obscure and largely forgotten figure.

Today, much of the wealth of the Osage has evaporated, as oil prices plunged beginning in the 1930s, thanks to over drilling and the discovery of new petroleum sources elsewhere in the world. As early as 1931, the value of an Osage annual headright had plummeted to $800. In 2012, a sale of three leases went for less than $25,000. The former boomtowns had turned into decaying and desolate ghost towns.

Although the Reign of Terror took place nearly a century ago, its memory haunts the Osage today. The archival research by historians today strongly suggests that Hale and his gang were not the sole perpetrators of the Reign of Terror. There were likely many more perpetrators and victims—for whom justice was never done. Some accounts place the true death toll in the scores, and possibly in the hundreds.

The Osage community has managed to persevere—the tribe now operates several casinos that generate tens of millions of dollars annually and, in 2011, received a $380 million settlement from the U.S. government in compensation for the decades of fraud and abuse. The Osage Nation has its own tribal government within Oklahoma and operates its own health, education, and welfare programs. And although the oil money is mostly gone, the old fear that the white man’s money would erase their identity has not come to pass, and the tribe proudly maintains its cultural heritage.

But the past can never be erased and the pain can never be forgotten. The fields and prairies of Osage County are forever soaked in blood.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of David Grann's "Killers of the Flower Moon" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Killers of the Flower Moon summary :

- How the Osage tribe had vast oil wealth, but had it seized by their murderous neighbors

- The brutal and unresolved murders of Osage Native Americans

- The complicated history of the FBI in profiting from the Osage murders