This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Blue Ocean Strategy" by W. Chan Kim and Renee Mauborgne. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is the difference between a blue ocean and a red ocean market? How do you prevent a blue ocean product from becoming a red ocean?

Kim and Mauborgne caution that when you create a blue ocean market, imitators will inevitably arrive, eventually turning it into a red ocean. There are two ways you can respond: 1) prolong your blue ocean, and 2) find a new blue ocean.

Let’s consider each of these approaches in turn.

Blue Ocean vs. Red Ocean

In their book, Blue Ocean Strategy, Chan Kim & Renée Mauborgne coined the terms ‘blue ocean’ and ‘red ocean’ to describe the competitive market space. They use the metaphor of a blue ocean to represent an uncontested market, and they contrast it with a red ocean, a marketplace where fierce competition has stained the water with the blood of the combatants.

The authors argue that any blue ocean market will inevitably turn into a red ocean when imitators will come for the market share. They propose two ways you can respond:

1. Prolong Your Blue Ocean

To prolong the benefits of your blue ocean, Kim and Mauborgne advise you to pursue a two-fold strategy:

- Maximize the defensive barriers that make your offering difficult to imitate, and thus prevent others from competing with you directly.

- Expand your blue ocean with ongoing innovation.

Let’s explore each of these strategic elements in more detail:

Establish Defensive Barriers

The authors identify a number of barriers that prevent companies from successfully imitating another company’s blue ocean strategy. You can leverage them to keep potential competitors out.

Legal barriers: Patents, permits, and other regulatory hurdles slow down competitors or exclude them entirely.

- (Shortform note: To make use of this barrier, you would secure as many legal protections as possible. Depending on the nature of your product, you may have several options. Utility patents protect functional innovations, design patents protect unique styling or appearance, copyrights protect original literary or artistic content, and trademarks protect brand insignia.)

Cognitive barriers: Because blue-ocean offerings are so typically so different from existing industry standards, people often ridicule them rather than try to imitate them.

- (Shortform note: You can maximize this barrier by letting your would-be competitors think they’re smarter than you. In The 48 Laws of Power, Greene advocates this as a strategy for gaining power over others: They won’t catch on to your strategies as quickly if they underestimate you. Obviously, you can’t play dumb in public, because you need to communicate the value of your product clearly to your customers. However, if you can find subtle ways to stroke your competitors’ ego, that might extend the cognitive barrier.)

Organization barriers: Sometimes, even when your rivals start paying attention because your strategy is getting traction, their organizational structure is not set up to imitate your operations. Replicating your blue ocean strategy might compete with their company’s core business (for example, it might entail retraining staff or redesigning a distribution channel), and organizational resistance and internal politics can delay competitive reactions for years.

- (Shortform note: Since you don’t have control over your competitors’ organizations, you would maximize this barrier by selecting unique characteristics for your offering. The more difficult it would be for the makers of alternative products to pivot and emulate your offering, the larger this barrier is.)

Image barriers: If your blue ocean brand image is significantly different from incumbents’, those incumbents might hesitate before replicating your marketing—for instance, luxury players might not want to suddenly offer economical alternatives.

- (Shortform note: You can maximize the image barrier through advertising that positions your product relative to existing alternatives. By reinforcing the alternative brands’ image, and presenting your product as a unique alternative, you make it harder for them to change their image.)

Momentum barriers: Kim and Mauborgne assert that if the strategic price is set at a level that attracts a mass group of buyers, the blue ocean entrant can rapidly develop a large, loyal customer base that is difficult for incumbents to recruit. If this customer base represents a large fraction of the market, it becomes difficult for a competitor to subsist on the remainder. This effect is amplified by economies of scale and network effects.

- (Shortform note: According to Ries and Trout, the best marketing strategy for a brand leader is to emphasize in your advertising that your product is the original, genuine article. This reinforces your image as the brand leader and subtly insinuates that competing alternatives are somehow fakes)

Expand Your Blue Ocean

Kim and Mauborgne assert that as others begin to imitate your product, it’s important to expand your blue ocean while it is still profitable. They observe that if you’re continually making innovative improvements, you’ll be harder to imitate, because it’s harder to hit a moving target. They suggest rolling out additional features that further enhance and differentiate your product, or encouraging customers and third-party developers to create add-ons that expand your product’s capabilities.

(Shortform note: As you make improvements or offer additional features, be careful not to dilute your brand. In particular, Ries and Trout warn against line extensions (rolling out additional products under the same brand or product line). They observe that the more diverse your product line is, the more vague your brand’s meaning becomes, because a brand has to stand for the entire scope of products and features that your market under it.)

2. Find a New Blue Ocean

However, Kim and Mauborgne also warn that there comes a point where it’s difficult to expand further on a unique product characteristic. When a blue ocean turns into a red ocean, you may need to look for other blue oceans to enter. They advise you to do this in parallel with extending your current blue oceans, so that when an older strategy reaches the end of its lifetime, your company has new opportunities for growth already lined up.

(Shortform note: There is potentially a significant distinction between opportunities for growth and opportunities for profit. If you are established as the brand leader in the market that your blue ocean strategy created, you may continue to profit from that product line after it becomes a red ocean. As long as the market is not disrupted by innovation that makes your product obsolete, market leaders tend to remain leaders. In fact, in The 22 Immutable Laws of Marketing, Ries and Trout point out that almost every red ocean eventually becomes a “two-rung ladder,” where the market leader has the majority of the market share, the alternative brand picks up most of the remainder, and any other competitors hold only a negligible portion of the market.)

Visualizing Your Long-Term Strategy

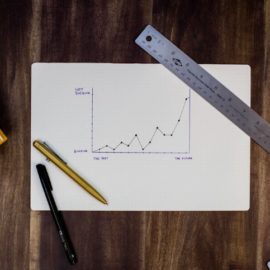

Kim and Mauborgne present a graphic tool for visualizing your organization’s long-term strategy by ranking your projects according to their level of innovation and plotting them on a timeline, with time progressing on the horizontal axis and the level of innovation represented on the vertical axis.

When you plot your current projects this way, the distribution of points gives you an idea of where your company is headed in terms of innovation.

(Shortform note: Adding a trend-line to the graph could help to highlight your innovation trajectory even more clearly.)

Here’s an example:

The authors divide the innovation spectrum into three areas:

- The standardized zone is for products and business ventures that copy existing products and compete in a red ocean. Standardized products may yield significant sales revenue at present, but offer little to no opportunity for growth.

- The intermediate zone is for products that improve upon existing products incrementally. They offer limited potential for growth.

- The cutting-edge zone is for blue ocean products. As blue ocean offerings, they offer the greatest opportunity for growth.

Analyzing Your Long-Term Trajectory

Kim and Mauborgne assert that If you practice blue ocean strategy, the trajectory of your organization will shift toward a greater concentration in cutting-edge and intermediate projects over time, as shown in our example graph. They argue that this shift toward more innovative projects leads to new growth. However, they concede that while standardized-zone projects offer little potential for future growth, they may still act as profit centers at present. Thus, ideally, you’ll have a variety of projects spanning the whole range of innovation in your portfolio.

(Shortform note: This concession seems a bit surprising, considering the authors’ earlier assertion that blue ocean startups were significantly more profitable than red ocean startups on average (14% of companies generated 61% of profits). However, it corroborates Ries and Trout’s observation that a leading product may generate profits indefinitely because market leadership tends to be self-perpetuating. Furthermore, given the higher risk involved in more innovative projects, maintaining a balanced portfolio of projects is inarguably prudent, and the authors’ concession illustrates that they remain open-minded even as they present the advantages of blue ocean strategy.)

Shortform Commentary: Graphing the Decay of Innovation

As we just discussed, Kim and Mauborgne plot projects as points or circles on a graph of innovation against time to visualize your company’s long-term trajectory.

However, the innovativeness of a given project or product decays over time: Building incandescent light bulbs was innovative in Edison’s day, but not today. As we discussed earlier in this chapter, every blue ocean eventually turns red as other companies begin to copy your product or strategy.

Thus, rather than graphing projects as points, it might be more accurate to plot them as downward-sloping lines to reflect how the innovativeness of each project declines over time. Then the graph for a company pursuing blue ocean strategy would look something like this:

This innovation decay plot can help you estimate when you will need to start new blue ocean projects to maintain your blue ocean strategy. Admittedly, to get accurate predictions, you will need to plot the slope of each line correctly, and estimating how fast each project will slide from the cutting-edge zone down into the standardized zone may not be easy. But historical precedents should give you some idea of how long it takes a novel idea in a given industry to become standardized.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Blue Ocean Strategy" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Blue Ocean Strategy summary :

- What blue oceans are, and how you create one for your business

- Why some businesses succeed in creating blue oceans, and why others fail

- The red ocean traps you have to avoid if you want business growth