This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Behind The Beautiful Forevers" by Katherine Boo. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is the central idea of the Behind the Beautiful Forevers book? Is Behind the Beautiful Forevers a true story?

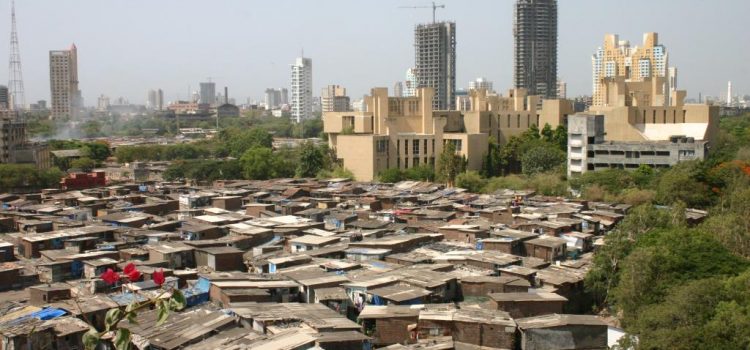

The book explores the diverse aspects of the poverty and hardship faced by the residents of Annawadi, a slum adjacent to the Mumbai International Airport. Behind the Beautiful Forevers is a true account of the lives of the residents of the Annawadi slum compiled through interviews and daily observations by Katerine Boo.

Read on to fully discover how the Behind the Beautiful Forevers book explores the daily lives of the people of Annawadi.

The Annawadi Slum

The Behind the Beautiful Forevers book is a nonfiction account of the lives of residents of a slum in Mumbai called Annawadi, which sat adjacent to the Mumbai International Airport. Katherine Boo, a U.S. journalist married to an Indian, spent four years learning the stories of Annawadi residents through reading public documents, conducting interviews, and observing people’s day-to-day lives. She tells the stories of real people—their names are unchanged—and how a globalized world affected them: Despite India experiencing a new era of wealth, opportunity, and increasing development, many people still struggled to survive day to day, even when working harder than ever.

Though governments can create policy to nurture the potential of their people, they sometimes just reinforce corruption instead, and people adapt to the system. In Annawadi, the poor tried to exploit one another to get ahead, and police and government officials exploited the poor, leaving the poor with little power and few resources. Nevertheless, many still hoped they could get ahead if they simply worked hard enough.

Part 1: The Residents of Annawadi

Annawadi, a half-acre slum, sprang up in 1991 during repairs to a runway of the Mumbai airport. The workers came from the state of Tamil Nadu and decided to stay in hopes they could get additional construction jobs. The land was swampy, and they worked to pack dry dirt into muddy areas to make it livable.

By 2008, Annawadi had 3,000 inhabitants. The slum had a sewage lagoon filled with garbage and pollutants. Airport construction workers also dumped waste there in the middle of the night. Some people living in the slum made so little money that they had to supplement their diet by catching rats and frogs living near the lagoon, or eating the grass that grew at its edges. People suffered air-pollution-related ailments, like asthma, as well as tuberculosis and other diseases.

The People Living Behind the Beautiful Forevers

A large concrete wall stood between the slum and main drive for the international terminal of the airport. On the wall, cheerful advertisements hawked luxury items to the overcity, or upper classes. One advertised Italian tiles with the slogan, “Beautiful Forever,” repeated over and over. Thus, the slum was located “Behind the Beautiful Forevers.”

Most people did work making cheap goods, like garlands for airport tourists or decorations for people’s car mirrors. Because globalization was generating new wealth in India, many people no longer felt limited by caste or religious affiliation and aspired to better jobs or living situations. However, full-time work and the stability it affords was increasingly hard to find.

As India modernized and became sensitive to the poor image created by the poverty of slums, there was periodically interest in razing Annawadi, but this had yet to come to fruition—a few huts were razed in 2001 and 2004, but most of the slum remained in place.

Abdul: Trash Seller

One of the most important Behind the Beautiful Forevers characters is Abdul Hakim Husain. He was a teenager who belonged to one of the few Muslim families in Annawadi. From a young age, Abdul helped his family earn a living by buying recyclable materials and garbage from trash pickers and selling it to recyclers. Being adjacent to the airport meant trash was abundant, whether from the luxury hotels surrounding the airport or tossed along the road to the international terminal. The variety and volume of trash coming from the airport, hotels, and construction projects reflected a booming global economy.

The Husains were looked down on for being Muslim. Most of the slum’s residents were Hindu, and tensions between Hindus and Muslims span centuries. Even the family’s modest success as garbage sellers drew suspicion from their neighbors in the slum. Muslims often had trouble getting decent jobs, such as those of hotel workers, in Mumbai.

Zehrunisa: Abdul’s Mother

Abdul’s mother, Zehrunisa, had many obligations to her family and her neighbors. Her husband, Karam, had made a payment on land where he hoped to build a home in a Muslim community just outside of Mumbai. He saw the move as a chance to give his family a comfortable living without frequent exposure to luxury goods they couldn’t afford, like the fancy cars and clothes seen near the slum. But Zehrunisa wanted to continue living in Annawadi, having found some freedoms she wouldn’t likely have in a predominantly Muslim community. For example, she could more readily confront her husband about things that upset her, something that might be frowned upon by more conservative Muslims who didn’t view it as a woman’s place to do so. She negotiated with her husband to make their hut in Annawadi livable instead of continuing to invest in the land in Mumbai.

Abdul’s Helpers: Sunil and Kalu

Abdul purchased garbage from garbage pickers who lived in the slum, keeping it in a storage shed near his family’s hut. Two garbage pickers he worked with, Sunil and Kalu, embodied the plight facing young boys, especially trash pickers, in the slum.

Sunil

Sunil lost his mother early in his life, and his father had taken him to an orphanage. Sunil became a trash picker when he was kicked out of the orphanage at age 11 because the nuns didn’t want to care for older children. He returned to Annawadi and learned to work hard to provide for himself, selling anything he could. Trash picking was grueling work, and Sunil worried that the work had stunted his growth and he’d end up a small man like his father.

Oftentimes, work involved climbing in and out of dumpsters. Risks included getting gangrene, maggot-riddled wounds, and lice.

Kalu

Kalu was known for two things in the slum—working in a diamond factory and scavenging aluminum and other scrap metal, a lucrative prospect. Oftentimes, the industrial facilities that produced these materials had guards or tall fences with barbed wire. Despite these barriers, Kalu could make multiple trips over barbed wire fences in a single night.

Sometimes, police told trash pickers where they could find trash in exchange for a cut of some of their earnings from the materials. In one instance, Kalu and Sunil worked together to take iron rods from a nearby industrial facility. It required expertly navigating the airport grounds, swimming through a polluted river, and going back the same way carrying the heavy pieces of metal, all in the middle of the night. They then sold these to Abdul.

Fatima: The Husains’ Next Door Neighbor

In Annawadi, the Husains’ Muslim community consisted of a man who owned a brothel and the family who lived next door. The mother of the family next door was named Fatima, but Abdul and others called her One Leg because she was born with a leg that tapered below the knee. People made fun of her for the amount of makeup and perfume she wore and her many extramarital lovers.

As a child, Fatima’s family had kept her at home and didn’t send her to school because of her disability. As an adult, she looked for affection where she could find it, but she was also known for her temper, beating her children or hitting neighbors with one of her metal crutches. Neighbors thought her rage was animalistic, but she disagreed—she was just as human as anyone else, yet because of her disability, she was treated as subhuman.

Asha: Aspiring Slumlord and Middle-Class Member

One powerful figure in the local community was Asha. In Asha’s childhood, the women in her family went hungry when there wasn’t enough food to go around. She wanted to amass enough money and power to avoid economic hardship, be a slumlord, and eventually, live outside the slum and reach the middle class. A “slumlord” was the person who ran the slum at the direction of the authorities and politicians. It wasn’t an official position, but everyone knew the role and its influence.

Asha found herself on the path to this role after falling on hard times. Her husband was an alcoholic and was often too drunk to work, affecting the family’s economic security. In her twenties, Asha turned to sleeping with powerful figures, like police officers and politicians, to support her family. The money she brought in helped put her daughter, Manju, through college. (Shortform note: The author also implies that Asha’s extramarital affairs ingratiated her with these figures, helping herself gain political and social power.)

Asha aspired to reach the middle class by broadening her network of connections through her political party, Shiv Sena—which promoted ethnic cleansing and distrusted Muslims, making the Husains suspicious of Asha’s work—and by working to make locals support the party. One way she did this was by helping people solve their problems, which in turn could make them sympathetic to her party. She also staged last-minute events, like protests and rallies, to show support for Shiv Sena politicians.

Asha wasn’t averse to exploiting the people around her for her own gain. In the long term, her goal was to sow discord that she could then help resolve for payment, building her family’s wealth so they could one day afford to live outside of the slum. She also hoped to gain political power by being elected a Corporator and overseeing a political ward, or voting district.

Asha’s political work reflected part of a larger effort on the part of the Indian government to address issues in India like poverty and women’s empowerment. However, most of these problems, as well as big ones like corruption and exploitation, continued to go unaddressed. For example, when the government initiated a group in which women pooled their money to give each other loans in times of need, Asha devised a system where women would pool their money and give it to women outside of the collective at a high interest rate. But when the foreign press needed a tangible example of India’s progress, the government would often send them to Asha to show her projects.

Though Asha was supposed to be a teacher at an elementary school, she had her daughter, Manju, do the teaching instead so she could tend to her political obligations.

Manju: Different Aspirations

Thanks to her mother’s efforts, Manju was the only slum resident attending college. In addition to her college studies, she spent most of her time caring for her family home—gathering water, cooking, cleaning, and more. She also spent two hours per day teaching. The school itself was Annawadi’s only school, taught out of Asha and Manju’s home. It was funded through the Indian government with help from a Catholic charity. Many schools in Mumbai were funded by unscrupulous charities that worked to line the pockets of the wealthy rather than serve school children. But the charity funding Manju’s school was better than most.

Asha thought Manju should only teach on days that someone from the government visited to check in on the school, but Manju wanted to be a teacher when she finished college, and she took pride in her work. Covering all of her responsibilities while completing her studies left Manju only four hours of sleep most nights.

Part 2: The Husains’ Conflict With Fatima

One fateful week, Abdul’s family began renovations Zehrunisa wanted for their home. In the construction process, they upset Fatima, their next-door neighbor. How Fatima chose to retaliate ultimately led to her death and drastically disrupted the life of the Husain family.

Hut Renovations

Zehrunisa and Karam planned to make the family hut more liveable. Zehrunisa wanted to install Italian tiles like the ones advertised on the Beautiful Forever poster, as well as a new shelf near her cooking area.

Fatima’s Anger

The renovation work involved many noisy tasks. To prepare the hut for the ceramic tiles Zehrunisa wanted, some family members were working to break up the stone floor and level it. Abdul was working to install a cooking surface, but to do so, he needed to cut into the wall that separated their hut from Fatima’s, the one-legged neighbor. Fatima periodically called out from her hut to complain about how loud the work was.

As Abdul was trying to install the cooking surface, he accidentally bumped the brick wall the Husains’ hut shared with Fatima, knocking mortar dust into a pot of rice she was cooking.

Fatima was upset and went outside to confront the Husains about the work. Zehrunisa met her outside and they began shoving each other. Fatima said that they needed to stop doing the work on the wall or Zehrunisa’s family would pay for it, but Zehrunisa contended they had built the shared wall and had a right to do work on their own home.

Fatima went to the police to file a complaint, but they largely dismissed the incident as too minor a squabble for them to deal with. Zehrunisa went to the station later to tell her side of the story and ended up with police officers asking her for bribes.

Meanwhile, while Zehrunisa was at the police station, Kehkashan, her eldest daughter, confronted Fatima outside her hut. She was frustrated with Fatima for complaining to the police, which had led to her mother being harassed for money. Kehkashan threatened to tear Fatima’s other leg off. Fatima retorted by calling Kehkashan a whore, which brought Karam out of the Husains’ hut. He told Fatima that they planned to finish the work and would try to avoid each other after that. But a little while later, he grew angry that Zehrunisa was still being held at the police station and stormed over to Fatima’s hut, threatening to have Abdul beat her. Abdul wanted no part of it. Kehkashan intervened and calmed her father down.

Fatima’s Burning and Hospital Stay

Fatima was mentally unstable, and she wanted a way to get back at the Husains for their threats and the renovations. She barricaded herself in her house, poured kerosene on herself, and lit herself on fire. Some of her neighbors had to break down her door to rescue her. From her hospital bed, Fatima told police that Abdul, Karam, and Kehkashan had burned her.

Meanwhile, the police knew that Fatima had set herself on fire from having talked to her 8-year-old daughter who witnessed it firsthand. They sent a government worker to take an official account of Fatima’s story. In India, it’s a serious crime to commit suicide. Therefore, the government worker framed Fatima’s account by saying she had been driven to do this by the Husains.

Despite knowing that the Husains didn’t do it, the police, the government worker, and Asha saw the incident as an opportunity to extract money from the Husains by convincing them to pay to make the charges go away. Fatima soon died of her injuries.

Abdul and Karam in Police Custody

Karam was arrested for burning Fatima, and Abdul surrendered to the police after a night of hiding in his trash pile. While in police custody, Karam and Abdul faced frequent beatings from police. Their detention was not entered in police records, and they were kept in a room for unofficial police business. It had a small hole in the wall where visitors could talk to those inside and offer small gifts, like cigarettes. Zehrunisa visited regularly to update Abdul and Karam on the status of Fatima and the case.

Zehrunisa had already paid some money when she originally visited the police station to argue their case, but the police wanted even more in exchange for making the case go away. Meanwhile, Asha and the government worker who took Fatima’s official statement were also asking for money to make the case go away. Abdul realized the jail was being run like a business where innocence could be bought for the right price.

Kehkashan, Abdul, and Karam in Jail

Kehkashan was sent to a women’s jail, Karam to the Arthur Road jail, and Abdul to a juvenile detention facility. In India, without paying for jail bonds, the accused could be held for years before facing trial. Zehrunisa had trouble providing collateral to pay for jail bonds to get her three family members out.

At first, Abdul was going to be sent to the same adult jail as his father, but Zehrunisa paid a bribe to a local school to falsify a school record for Abdul, showing that he was 16. She didn’t know his age because families that were struggling to survive didn’t often keep those records.

Eventually, a judge ruled that Abdul wasn’t a flight risk and could live at home until his trial as long as he promised to check in with the jail three days per week.

Zehrunisa told Abdul that his trash business had collapsed in his absence. Abdul decided to restart his business, but he felt determined to walk a more virtuous path. This meant not buying stolen materials from the scavengers and being okay with the income he’d earn from running his business three fewer days per week to meet the jail’s check-in requirement.

Part 3: Marriages and Deaths

Behind the Beautiful Forevers highlights how Annawadi’s residents attempted to make a living, secure marriages for their children, and find opportunities to climb the social ladder. Their motivation to do so sometimes stemmed from trying to escape worse circumstances in economically depressed rural areas. But sometimes, they couldn’t overcome their challenges and suffered violent deaths or suicide.

Asha and Manju: Rising Through the Ranks

Asha took Manju on a trip to her home region of Vidarbha, an agricultural area, to look for a husband for her daughter. Asha hoped to lift her family further out of poverty by marrying Manju to a decently wealthy family. While visiting Vidarbha, they found a soldier who was interested in marrying Manju; he met with Asha and Manju to discuss it.Though Asha had liked the man, and he was somewhat wealthy, her husband objected to the marriage because he believed army men tended to be heavy drinkers.

Manju hoped to marry someone who wouldn’t take her away from her life in Mumbai. When she and Asha returned to Annawadi, they spent some time trying to improve their appearances and build their social networks. Asha hoped this would expand Manju’s marriage prospects and prepare them to fit into high-class society.

Accidents and Suicides in Annawadi

Annawadi saw a number of deaths and suicides each year. Along Airport Road, it was common for trash pickers to get hit by cars. Passersby from the slum were often too busy with their own affairs to call the authorities for help, or they feared the authorities.

The local police, for their part, felt increasing pressure from the government to maintain a safe environment around the airport to bolster its image. Officially, only two murders were recorded in the area around the airport, from slums to hotels, over a two-year period. However, deaths were likely undercounted. The deaths of slum residents were largely regarded as a nuisance rather than a problem to fix.

Kalu’s Story

Kalu, one of the young trash pickers Abdul worked with, had come to Annawadi from another slum after his mother’s death. He’d become known for scavenging high-quality recyclables from the airport grounds, but he ran into trouble with the police for doing so—in the eyes of the law, he was trespassing on airport grounds and stealing the goods. The police made a deal with Kalu: He could continue scavenging if he acted as an informant on drug dealers operating around the airport.

Kalu agreed but lived in a constant state of stress. He feared both the police and the powerful drug dealers he ratted on. After leaving Annawadi and trying unsuccessfully to work in his family’s pipe fitting business, Kalu returned to Annawadi. But he was soon found dead on Airport Road. The police recovered the body and concluded that Kalu had died of tuberculosis, but not before some boys from Annawadi had looked at the body. They could see he had severe injuries and said he’d been murdered.

After Kalu’s death, the police rounded up five trash pickers living without shelter in Annawadi, held them, and beat them. To prevent more people from ending up dead along Airport Road—and tarnishing the airport’s image—they gave the trash pickers an ultimatum: Either stop picking trash along Airport Road and at the airport, or face being charged with murdering Kalu. The police didn’t tell the boys that they had already attributed Kalu’s death to tuberculosis in their official report.

Part 4: Recession and Trial

By 2008, the great recession had begun in the U.S. and the Behind the Beautiful Forevers book showed how it affected the livelihoods of Annawadi residents in numerous ways. The court began the trial of Kehkashan and Karam, but it was a long process.

Global Recession Felt in Annawadi

The U.S. recession affected the local economy of Annawadi in complex ways, including reducing jobs and scrap metal prices. At first, the trash pickers thought things would pick up with the start of the tourist season, but after a series of terrorist attacks in Mumbai’s hotels, train stations, and taxis, they realized tourists would be too afraid to come, reducing the waste stream. Many slum residents had to start eating rats and frogs again, unable to afford enough food.

The Fate of the Husain Family

Karam and Kehkashan’s case was put on a fast track—their trial began after they had spent months in jail rather than years. If convicted, they faced 10 years in prison. Abdul would face a separate trial with separate charges.

Though the fast-track system shortened the waiting time for a trial, judges often heard dozens of trials at the same time, holding short hearings for each case each week. So the trials themselves still took months to finish.

Zehrunisa found a lawyer to argue Karam and Kehkashan’s case. Karam hoped they would be exonerated. However, he was concerned that the prosecution was planning to call many witnesses who hadn’t observed Fatima’s burning or the words Karam and Kehkeshan said to Fatima.

The government worker who’d taken Fatima’s statement in the hospital tried multiple times over the course of the trial to convince the Husains to pay her to help resolve the case. The first time, she threatened to embellish the details of the case, and the second time, she said that Fatima’s husband was willing to drop the case in exchange for about $4,000. However, because the case was being brought by the state, it couldn’t be called off for any amount of money. She hoped that the Husains wouldn’t realize this, but they saw through her scheme and refused once again to pay her off.

The Husains finally were found not guilty of burning Fatima. Abdul continued to check in at the juvenile prison, and his family feared that his case might drag on forever.

Abdul had resolved to live a more virtuous life. If most people were like water, he wanted to be like ice—made of the same substance, but elevated above others by how he lived. But as time dragged on, and his trial wasn’t scheduled, he became more disillusioned. He told Allah that he felt as though the ice inside him was melting, and he was becoming water, just like everyone else, because of how the world worked: No matter how much he tried to do the right thing and get ahead, he couldn’t.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Katherine Boo's "Behind The Beautiful Forevers" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Behind The Beautiful Forevers summary :

- A nonfiction account of the lives of residents of in one Mumbai slum

- How the globalized world affects many people in India

- A story of poverty, exploitation, and the struggle to survive