This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Mother Tongue" by Bill Bryson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Do you ever just stop what you are reading and marvel at the richness and the beauty of the English language? What do you think sets English apart from other languages?

English is not only the dominant language of global business and politics but also of literature and oratory, capable of eloquently expressing the most powerful human emotions and desires. Therein lies the beauty of the English language—it is both expedient and expressive.

Let’s explore the beauty of the English language and the unique traits that make it so rich and evocative.

The Beauty of the English language

The beauty of the English language lies in its unique properties, quirks, and incomparable flexibility that sets it apart from other languages.

English Place-Names

One of the best ways to glimpse the richness and the beauty of the English language is to explore names, especially place-names and personal names. Place-names in England are often perplexing to outsiders because of the divergence between their spellings and pronunciations: Leicester is pronounced “lester,” Worcester is pronounced “wooster,” and Postwick is pronounced “pozick.” These names are often the product of waves of conquerors—Celts, Romans, Angles, Saxons, Vikings, and Normans twisting and reshaping the names of the places they encountered. Thus, British place-names bear the stamp of peoples from all across Europe.

Many names of streets, pubs, and towns are remarkably colorful and evocative. London boasts streets named Crooked Usage, Ha Ha Road, and Bleeding Heart Yard, to name just a few. Classic English pubs often have baffling names, like the Quiet Woman, the Nobody Inn, the Bunch of Carrots, and the Cat and Custard Pot.

Many English pub names harken back to old aristocratic heraldry and coats of arms, or were meant to signal loyalty to an old medieval political faction. Often, they needed to have colorful and unique names and symbols to make themselves identifiable to a population that was largely illiterate. Others, like the Bishop’s Finger and the Monk’s Head have names rooted in religious orders.

American Place-Names

Not to be outdone, the United States has its own roster of names that bedevil non-natives. Like in England, many of these names are products of conquests of indigenous peoples. Thus did Missikamaa become Michigan and šhíyena become Cheyenne. Similar processes unfolded with place-names that had their origins in French, Dutch, and Spanish names. The United States also has colorful names in abundance, from Screamer, Alabama to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico.

Some American place-names or nicknames have unknown or dubious origins, like the Hawkeye State (Iowa) or the Hoosier State (Indiana). Perhaps the most famous misnaming of a place by outside conquerors is the West Indies. Europeans who first journeyed to this part of the Caribbean believed that they had arrived in India (largely due to a glaring navigational and cartographic error by Christopher Columbus). Hence the name for the place and the name that has stuck to the indigenous peoples of the New World ever since: Indians.

Surnames

English surnames tell a rich and interesting story. For much of the Middle Ages, ordinary people did not have any need for surnames. They lived in small communities in which they knew everyone, so personal names like John or William were wholly sufficient: you might be the only John or William in the village.

This began to change in the later Middle Ages, as the royal government began to more aggressively and efficiently collect taxes, which required a more thorough way of tracking everyone who owed money to the crown. Registering individuals by personal name and surname turned out to be an effective way to do this.

Generally speaking, surnames derive from place-names (John Lancaster), nicknames (John Whitehead), trade names (John Smith), or familial relations or patronymics (John Son-of-William, or John Williamson). Interestingly, smith-work was so common that Smith or its equivalents are today extremely common in every language, from the German Schmidt to the French Ferrier to the Italian Ferraro.

English surnames that are rooted in place-names often bear the names of obscure or thinly populated places. At first glance, this seems counterintuitive—shouldn’t there be a lot more Sarah Londons than Sarah Dovers? But it actually makes sense. People wanted surnames that distinguished themselves from others. Lots of people came from big cities like London and York, so these wouldn’t be good surnames to adopt, unless you were moving to a rural area, in which case your place of origin in an urban center would be distinctive.

Although the most common names in America are of British origin, certain British names are far more common in the US than in the UK. Johnson, for instance, is more prevalent in America because the many Jonssons and Johanssens that came to America from Scandinavia and had their names anglicized to Johnson. When immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe came to America, they, too, often had their names changed at ports of entry, either voluntarily or by immigration officials.

Obscenity and Blasphemy

One of the best ways to get a true flavor of the beauty of the English language is through its swear words. Most languages feature swears, although some, like Japanese, do not. Swear words derive their power from the fact that they are highly emotive, as well as forbidden. We reach for these words to express extreme emotions: fear, surprise, joy, anger.

Swear words and phrases are remarkably varied from language to language, but they tend to be oriented around two themes: obscenity, which is either the disgusting and/or taboo (often having to do with bodily functions or sex); or blasphemy which involves sacrilege or invoking the name of God in vain. In English, shit, piss, fuck, and cunt would fall into the former category; hell, damn, goddamn and Jesus Christ (in certain contexts) would fall into the latter.

Many taboo words in English are actually quite old, with some of them having origins in Old English, from the days before the Norman Conquest. Shit is very old, dating back to the shite of the 1300s and the Anglo-Saxon scītan before that. Fuck may have Latin origins and was first printed in 1503, meaning that it was almost certainly widely used before that date.

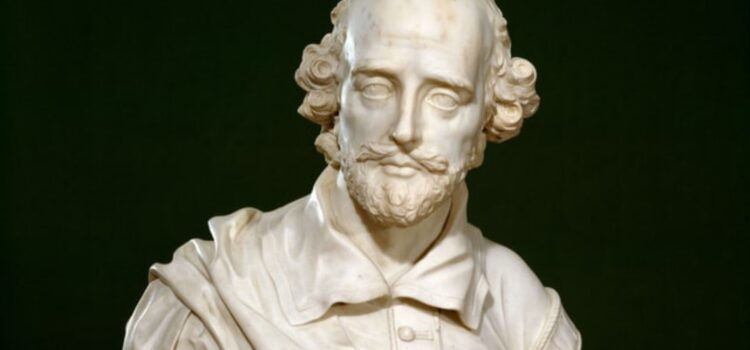

Throughout the history of the English language, there have been shifting definitions of which words were and weren’t considered offensive. For much of the Middle Ages, the strongest words in modern English would scarcely raise an eyebrow. Cunt is perhaps the most obscene word in the English language, but it was entirely commonplace and inoffensive a few centuries ago. It features in the works of Chaucer, and even Shakespeare had a famous winking reference to it through a double entendre in this memorable exchange from Hamlet:

Hamlet: [To Ophelia] Lady, shall I lie in your lap?

Ophelia: No, my lord.

Hamlet: I mean, my head upon your lap.

Ophelia: Ay, my lord.

Hamlet: Do you think I meant country matters?

Ophelia: I think nothing, my lord.

Hamlet: That’s a fair thought to lie between maids’ legs.

Many English cities of the time had a Gropecunt Lane, streets where prostitution was common. This was entirely unremarkable, simply an extension of the practice of naming streets and boroughs after the economic activity that took place there, analogous to a Butcher’s Alley or Baker’s Court.

By contrast, words and phrases that seem relatively harmless today were considered extremely taboo during the pious Middle Ages. Many of these were blasphemous or sacrilegious in nature, taking the name of God in vain or making explicit reference to God or Jesus’s body. Damn, hell, or phrases like “by the blood of Christ,” “God’s blood,” or “God’s wounds” (the last of which was shortened to the minced oath zounds), were far more offensive than shit or piss.

The Beauty of the English Language Lies in its Variety

Another way we can appreciate the beauty of the English language is with its great variety of sounds. Linguists have debated just how many different sounds are present in English. The figures vary depending on how one defines a unique sound. One study has found 90 separate sounds for just the letter t, but, regardless of the precise number, English is vastly richer in the variety of its sounds than other widely spoken languages (the whole Italian language, for example, has only 27 sounds).

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Bill Bryson's "The Mother Tongue" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Mother Tongue summary :

- How English became a global language

- How the invention of the printing press led to standardization of written English

- Why English dictionaries are the most comprehensive found in any language