This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "NeuroTribes" by Steve Silberman. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What were the problems with Hans Asperger’s autism research? How did it mislead future autism researchers?

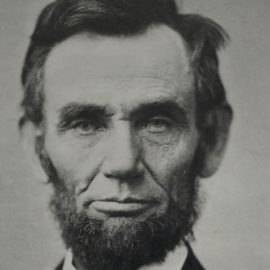

In his book NeuroTribes, Steve Silberman writes that the history of autism research began with the work of Austrian physician Hans Asperger in the 1930s and 1940s. Asperger was an influential figure and thus, his flawed research had long-lasting consequences.

Continue reading for a look at the flaws in Asperger’s research.

Asperger’s Thesis: Consequences for Future Autism Research

In 1944, explains Steve Silberman in NeuroTribes, Hans Asperger published his thesis on autism. His goal was, in part, to demonstrate that autistic people could make valuable contributions to society in the hope that this would help spare them from the Nazis’ slaughter of those they considered “worthless.” Because of this, he chose to focus his paper on just four specific cases out of the hundreds of autistic children he’d studied. The children in these four cases had no severe impairments and displayed exceptional abilities in math and science. He tried to make the case that people with such abilities could be useful to the Nazis as code breakers.

According to Silberman, this well-intentioned choice had long-lasting, damaging consequences for the field of autism research: Whereas Asperger knew that autism wasn’t rare and that it was a broad spectrum, his published work made it seem like autism was strictly defined and not at all severe. This led other researchers to believe that the condition Asperger studied was a separate condition from autism. (It also later led to the development of the diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome, now colloquially understood to be a subtype of autism, though it no longer appears in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM).

Asperger’s Narrow Focus: The Roots of “Aspie Supremacy”?

Asperger’s argument was that autistic people didn’t deserve to die because those with exceptional abilities could be “useful”—but some argue that this stance is problematic in its own right. This argument used the same logic as the Nazis’ eugenism: that a person’s “usefulness” to society determined their right to live. The unspoken corollary of that argument is that autistic people who didn’t appear to be “useful” (for example, those with severe impairments) did deserve to die. Such writers also link Asperger’s distinction to what’s now known as “Aspie supremacy,” or the perception that autistic people who appear “high-functioning” are superior to those who appear “low-functioning.”

Since “Asperger’s” has been removed from the DSM, some also argue that people who continue to use that term to distance themselves from the rest of the autistic community may be reinforcing the Aspie supremacist framework. However, many autistic people still identify strongly with the terms “Asperger’s syndrome” or “Aspie.” Some suggest that the specificity of the term can help more clearly convey an individual’s particular subtype of autism. And still others contend that we shouldn’t try to convey a person’s entire autistic profile with a single term and should instead use the term “autism” followed by a brief description of their individual experience of autism.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Steve Silberman's "NeuroTribes" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full NeuroTribes summary:

- The truth behind the common misconceptions about autism

- How society’s perception of autism has evolved since the 1930s

- The most effective treatments for autism spectrum disorder