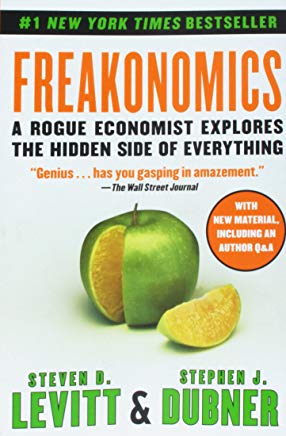

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Freakonomics" by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

As the world has become more specialized and complex, people have come to rely more and more on experts to guide them through major life decisions. This is largely driven by fear of making a wrong decision that might result in financial ruin or even physical harm.

As we’ve discussed above, however, experts are hardly neutral arbiters of truth who are selflessly devoted to guiding you through the trials and tribulations of a staggeringly complex world. Rather, they are often self-interested, equally fallible humans who seek to use their superior information to gain an advantage on you. This unequal distribution of information between parties to a transaction is known as information asymmetry.

Think of the mechanic who tells you that you need to replace parts of your engine that you’ve never heard of to be able to pass your vehicle inspection. Or the doctor who orders that MRI that you’re not quite sure you needed. Or the car salesperson who insists that you need all of those pricey add-on safety features. All of these experts know perfectly well that you know nothing about their business. Often, your information deficit is their gain, especially if they have strong incentives to profit.

(Shortform example: the 2008 Financial Crisis was another story of asymmetric information. Financiers created products like derivatives and collateralized debt obligations, whose larger implications many investors simply did not understand. When the housing market collapsed, those investors who bought these products were wiped out, while the sellers, who possessed a major information advantage, made a tidy profit.

Note: This is not to say that all experts with an information advantage consciously deceive unknowing victims. There are many fair and well-meaning experts. But a tricky thing about incentives is that they can bias someone subconsciously.)

Example of Asymmetric Information: Your Real Estate Agent vs. You

When you’re selling your house, it’s natural to assume that your real estate agent will work hard to secure the best deal for you. After all, why wouldn’t she? The incentive seems aligned: the more she sells your house for, the higher her commission will be, right?

Unfortunately, your incentives aren’t as aligned as you think.

Let’s say you sell your house for $500,000. With the customary 6 percent of the sale price going to the agent, she should be pocketing $30,000 from the deal. But that’s before we consider a few other factors that cut significantly into her final take:

- The buying agent’s fee.

- Her own agency’s fee.

- The selling costs (which are borne by the agent).

In fact, her real takeaway from the deal is more like 1.5 percent, or $7,500. And if you think you can ask for more and want to sell for $520,000? Sure, you pocket an extra $18,800, but your agent would only take home an additional $300. And given that she would have to put in all the extra work, place all the extra ads, and turn away new clients, this hardly seems like a worthwhile reward.

Now here’s where the information asymmetry comes into the picture. Given her vastly superior knowledge of the real estate market, she knows how to exploit your relative ignorance. She’ll work her hardest to convince you that the lowball $500,000 is the best you’re going to receive and that you’d better take it before they withdraw or lower it. Of course, she knows that’s not likely to be true, but she’s more interested in having you making a quick deal than in holding out for a better one.

This contrasts with how real estate agents behave when selling their own homes. When we study the public data of home sales in the Chicago area, we see that real estate agents:

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Freakonomics" at Shortform c . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Freakonomics summary :

- How every single person behaves according to incentives

- Why you should tune out experts and make your own decisions

- The surprising truth behind why crime declined so much in the 1990s