This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "How Democracies Die" by Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

When did political polarization start in the United States? At what point did partisan struggle start to subside?

Immediately after the ratification of the United States Constitution, the American political system was characterized by intense partisan warfare between America’s two original parties—the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. The partisanship subsided following the demise of the Federalist Party, only to escalate again in the 1850s. Eventually, the partisan struggles subsided and the democratic norms were restored.

Here is a brief history of American partisanship.

The Era of Good Feelings

Immediately after the ratification of the U.S. Constitution, the American political system was characterized by intense partisan warfare between America’s two original parties—the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans.

The two parties viewed each other with mutual hostility. Both parties engaged in constitutional hardball, most notably through manipulating the size of the Supreme Court (whose size is not fixed by the Constitution) to maximize partisan advantage and censorship laws that targeted newspaper editors sympathetic to the other party.

Levitsky and Ziblatt argue that this tit-for-tat cycle only subsided when a new generation of politicians rose to prominence in the aftermath of the War of 1812 following the demise of the old Federalist Party. These leaders had come of political age under the Constitution and were not defined by the bitter struggles of the early republic. They accepted the give-and-take of democratic politics.

| Truly an “Era of Good Feelings”? This age of post-partisan reconciliation has even been given a name by historians: “The Era of Good Feelings.” It typically refers to the period that coincides with the presidency of James Monroe (1817-1825). One of Monroe’s chief aspirations as president was to inaugurate an era of political life free from the bitter partisan struggles that had marked the years immediately following independence. In an early precursor to modern political campaigning, he even launched a goodwill tour across the country in the summer of 1817, meeting with as many Americans as he could in an effort to transcend the ideological and regional conflicts that had so divided the young country. However, this supposed era of comity was, in reality, far more hostile and contentious than Levitsky and Ziblatt portray it in How Democracies Die. Monroe, a Democratic-Republican, partially achieved this era of post-partisan togetherness by using the powers of his office to harshly attack and eliminate the rival Federalists, whom he viewed as traitors for having failed to support the War of 1812. He shut them out of all federal patronage and worked behind the scenes to remove them from public offices they held at both the federal and state levels—actions that would appear to violate Levitsky and Ziblatt’s democratic norms of mutual toleration and institutional forbearance. |

Slavery and the Repolarization of Politics

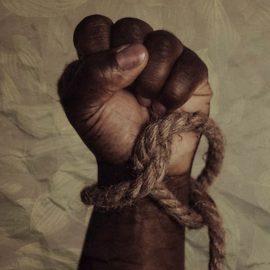

According to Levitsky and Ziblatt, partisan tensions escalated once again in the 1850s during the struggle over the future of slavery in the United States. The rise of the anti-slavery Republican Party in the northern states during this time prompted a harsh reaction from the more southern-based Democratic Party, which viewed the Republicans as an existential threat to the South’s racial, social, and economic order. Mutual toleration was dead once again, paving the way for the U.S. Civil War.

After the northern victory in the war, Democrat Andrew Johnson acceded to the presidency following Lincoln’s assassination. Congressional Republicans, angered by Johnson’s insufficient commitment to protecting the civil rights of formerly enslaved people, began a new cycle of hyper-partisan brinkmanship. They used their veto-proof majorities to pass acts severely curtailing the president’s authority. This culminated in 1866 with Johnson’s impeachment in the House of Representatives and near-removal by the Senate.

Clearly, the Constitution hadn’t prevented American democracy from spiraling into civil war and dangerous partisanship. American political system needed better norms to guide politicians’ behavior.

| The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson Levitsky and Ziblatt treat the partisan back-and-forth following the Civil War, during the presidency of Andrew Johnson, as a dangerous era of brinksmanship that could have torn apart the country’s clearly fragile democracy. If we accept their characterization of Johnson’s impeachment as a particularly alarming episode, then it’s worth noting just how close it came to being even worse. As the authors note, Johnson was impeached in the House of Representatives for alleged misdemeanors (stemming from Johnson’s refusal to abide by acts passed by congressional Republicans that he believed unconstitutionally limited his presidential authority). But two-thirds of the U.S. Senate would have been required in order to convict Johnson of the charges and remove him from office. As it happened, Johnson was acquitted in the Senate by a single vote. As the roll call was taking place, a Republican senator from Kansas named Edmund Ross decided to switch sides and cast a “Not Guilty” vote for Johnson, stunning his fellow Republicans, saving Johnson’s presidency—and, possibly, stopping institutional forbearance from being further violated. |

The 20th Century: The Golden Age of American Norms

In Levitsky and Ziblatt’s analysis, the political system eventually regained the democratic norms it needed to survive when the Republican Party began abandoning its historical commitment to black civil rights (the Republicans were generally the more progressive of the two parties on these issues at this time).

Following the contested presidential election of 1876, Republicans and Southern Democrats came to an agreement known as the Compromise of 1877. This agreement let the Republicans take the White House, in exchange for the withdrawal of federal troops from the South. After the removal of the troops, white Southern Democrats rewrote state constitutions and systematically disenfranchised black citizens.

This was the basis for the great mid-20th-century era of cooperation, when mutual toleration and institutional forbearance held strong and major legislation, Supreme Court appointments, and even constitutional amendments regularly passed with strong bipartisan majorities. Racial apartheid, argue the authors, was the glue of bipartisanship in the 20th century.

| The Era of Bipartisanship As noted in The New Yorker, the decades running from the New Deal of the 1930s to the Watergate crisis of the 1970s were the high-water mark of bipartisan governance in the United States. It was a time of political dominance for the Democratic Party, which won eight out of 11 presidential elections from 1932 through 1976 and held large majorities in both houses of Congress throughout almost the entire period. But it was not necessarily a time of progressive or liberal governance, despite the hammerlock on federal power held by Democrats. Congressional politics at the time were dominated by the “conservative coalition” of Southern segregationist Democrats (usually known as “Dixiecrats”) who headed most of the major congressional committee, and their conservative Republican allies. Together, they were able to keep a range of progressive legislation—from national health insurance to expansion of Social Security to increased federal funding of schools—from passing into law. This cross-party cooperation toward generally conservative policy ends was only possible in a relatively non-polarized era for U.S. politics. The Democratic and Republican parties were not yet neatly sorted into distinct ideological camps, as social and economic conservatives still had significant clout within both parties. There was less incentive for either party to violate norms to try to gain advantage over the other because their ideological convergence on many issues made them something more akin to coalitional partners rather than enemies. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt's "How Democracies Die" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full How Democracies Die summary :

- How shared norms are essential for preserving democracy

- Why the Trump presidency threatened those shared norms

- Why democracy goes beyond individual leaders and parties and must be a shared enterprise among committed individuals