This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "A People's History of the United States" by Howard Zinn. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

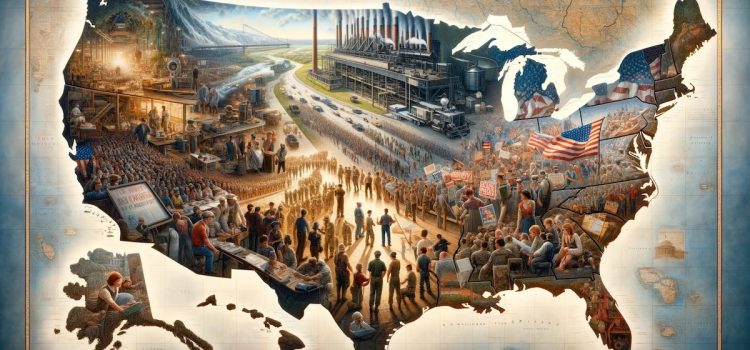

What does America in the 20th century look like from “the people’s” perspective? What were the aims of the elites, and how did they seek to achieve them?

Howard Zinn provides a “people’s history” of America in the 20th century. He covers the labor movement, the Great Depression and the New Deal, New Imperialism, the World Wars, the Cold War, and significant social movements.

Read more to get Zinn’s take on America in the 20th century.

The Labor Movement in America

Zinn’s “people’s history” of America in the 20th century takes aim at what he calls the American elite. This is the lens through which he discusses history, including the American labor movement that began in the 19th century. Zinn writes that, in response to their grim conditions, workers organized (illegally at the time) and advocated better working conditions, higher pay, and other benefits. This usually involved striking, or laborers refusing to work until their demands were met.

Often, capitalists, police, hired thugs, and sometimes the National Guard attacked and killed strikers. Initially, labor organization was sporadic, small, and rarely effective—employees of one plant would walk off the job in protest only to be replaced by other people looking for work. But, over time, it grew in scale and ambition. Zinn notes several important elements of the labor movement: trade unions, socialism, and radical organizers.

1) Trade Unions

Zinn explains that the largest form of labor organization were trade unions: organizations of workers within a specific trade, such as teachers and longshoremen. These unions attempted to monopolize their specific form of labor, then used this monopoly to make demands of their employers. Trade unions also worked together through larger organizations such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL), founded in 1886.

2) Socialists and the Socialist Party of America

Zinn explains that socialism, or the political and economic ideology promoting collective ownership of property, rapidly gained popularity in late 19th and early 20th century America. Socialists came from a number of backgrounds: They were trade unionists, rural populists, idealistic academics, immigrants, and so on. Their politics were anti-war, anti-imperialist, pro-worker’s rights, pro-government regulation, and pro-social safety nets. Socialists made their largest gains under the banner of the Socialist Party of America (or SPA), a political party founded in 1901.

The SPA also overlapped with women’s rights and women’s suffrage groups of the era, though they weren’t totally aligned; socialists tended to prioritize economic causes over social ones. In addition, while the SPA preached racial equality and allowed people of all races to join, it didn’t advocate particularly hard for Black Americans despite it being a dangerous era for them due to white mob lynchings and horrible working conditions.

3) Radicals, Militant Unions, and the IWW

Zinn makes the case that radical organizers were also important for the labor movement. Their violence and serious disruptions to business put large amounts of pressure on capitalists to make concessions. Particularly toward the end of the 19th century under intense economic strain, more radicals emerged. Anarchists like Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman believed that, to achieve the socialist dream of collective ownership, current political and economic systems had to be destroyed. They argued that, in the right context, violence—including bombings and assassinations—was appropriate to achieve these ends.

Founded in 1905, Industrial Workers of the World, or IWW, was a militant union accepting all workers regardless of their industry, race, sex, or immigration status. Instead of negotiating contracts with management like trade unions, the IWW traveled the country supporting and organizing massive ‘general strikes’ of all workers in a given area. They didn’t condone violence except in cases of self-defense, but the nature of their cause meant they often clashed with and were heavily persecuted by law enforcement.

The Labor Movement’s Obstacles

Despite the growing size and scale of the American labor movement in the 19th and 20th centuries, Zinn argues progress was still slow and difficult. He notes three significant obstacles of the labor movement: institutional resistance, internal divisions, and moderates.

1) Organized Institutional Resistance

Zinn explains that a majority of institutions in American society worked together against the labor movement. Police, private security, and even the National Guard often used violence to break up strikes and force people back to work. In addition, major newspapers and the judicial system persecuted labor organizers. For example, the first Red Scare (a political purge of the left and moral panic around communism in the early 1920s) led to a coordinated campaign of anti-labor propaganda, mass prosecutions, and violent suppressions of strikes, contributing to the IWW’s loss of power and influence.

2) Internal Divisions

Divides within the labor movement often prevented workers from organizing together, or in some cases, even turned them against one another. These divides were often based on racial, ethnic, or gendered prejudice. Divisions occurred along ideological lines—the Socialist Party split in 1919 over whether it would support the newly formed Soviet Union. Pro-Soviet and more radical members left the SPA to form the Communist Party USA, halting the SPA’s growing momentum.

3) Moderates

Zinn argues thelabor movement was alsohampered by moderates channeling time, energy, and money into inadequate reforms. In particular, these moderates often pushed for reform “within the system” via electoral or legislative victories. However, these were insufficient at best and ineffective at worst, Zinn argues, as electoral politics were structurally designed to serve elite interests. For example, the National Labor Union discouraged strikes in favor of lobbying Congress for labor reforms and running candidates in elections. However, their few legislative successes were bypassed with loopholes, and their candidates lost by large margins.

The Great Depression and the New Deal (1929-1939)

Economic and political circumstances of the late ’20s through the ’30s saw significant shifts in the American labor movement, explains Zinn: most significantly, the Great Depression and New Deal.

The Great Depression

The activity and militancy of the American labor movement tended to fluctuate along with the desperation of workers and the state of the economy. Therefore, the Great Depression—a severe economic downturn that began in 1929 and lasted over a decade—caused labor unrest to skyrocket to an all-time high. For the first several years of the depression, elites in business and government had no clue what to do, leaving the American people to fend for themselves. Communists, socialists, and labor activists organized their communities to support one another, engage in massive, citywide strikes, and pressure elites to make concessions.

Some activists didn’t coordinate with Black Americans during the depression—they either weren’t interested or worried that doing so would alienate potential white, working-class supporters. The Communists were one of the few groups who made a serious effort to build a cross-racial coalition during this era, secretly helping black laborers organize themselves.

The New Deal

Concessions to the American public came in the form of the New Deal, a series of laws and social programs under President Franklin Delano Roosevelt designed to help the country recover. However, Zinn argues the New Deal was still ultimately a project by and for elites—it shared just enough wealth and power with the American people to prevent all-out rebellion while centralizing power in the federal government via appointee-only bureaucracies. In addition, the New Deal largely ignored the plight of Black Americans—Roosevelt needed the support of Southern segregationists to pass his desired policies, so he didn’t pursue anti-segregation or anti-lynching measures.

For example, the Wagner-Connery Act in 1935 legalized labor unions and formalized the process of labor-management negotiations. This law provided some concessions to labor—employers could no longer fire workers for being union members, for example. However, it also channeled popular energy away from using strikes to cause broad social change and toward internal union politics and negotiating financially beneficial contracts.

Rising Empire (1898-1945)

For centuries, American expansion had been fueled by the frontier—the “free” land and resources of the West provided a way for enterprising capitalists to make and expand their fortunes. But, by the end of the 19th century, Zinn explains, the American frontier had closed. Land and wealth in the US were largely divided up among a select few elites. To continue increasing their wealth, elites had to start influencing and controlling other countries and peoples—they had to make America an empire.

Early Imperial Projects

Around the turn of the 20th century, the US engaged in a number of imperial projects, influencing, controlling, and even conquering other nations and colonies. These accomplished two major goals for elites: First, they created new markets for American goods and new sources of cheap labor and natural resources. Second, they attempted to soothe domestic unrest by appealing to patriotism and nationalism—if everyone thought of themselves as part of a collective American project, they would pay less attention to class divisions within the country.

While elites and major newspapers tended to support these projects, Zinn suggests popular opinion was mixed. Trade unions occasionally supported colonial ventures, believing they would improve business. On the other hand, the Socialist Party was staunchly against American imperialism, and many Black Americans sympathized with or even supported peoples oppressed by the US abroad, recognizing their common struggle.

For example, the 1898 Spanish-American War saw the US intervene in the Cuban Revolution to secure American economic interests in the region. After winning the war in 1902, the US secured control over newly independent Cuba’s government and economy. The US also annexed a number of other Spanish colonies following the war, including the Philippines—after stomping out Filipino resistance in a bloody three-year campaign.

The World Wars

The two world wars represented some of the first times the new American empire acted on a global stage, Zinn explains. He outlines American participation in each war and the popular response to them:

World War I (1914-1918)

In 1914, World War I began—what Zinn describes as a years-long bloody and pointless conflict between European imperial powers. He argues the US joined the war in 1917 to protect American elite financial interests despite mixed or even anti-war public opinion. Before and early on in the war, American elites developed strong business ties with and made large investments in Allied nations. Going to war allowed them to protect these investments.

Elites tried to garner support for the war through propaganda campaigns and suppressing dissent. For example, the Espionage Act of 1917 made criticizing the war essentially illegal, and it was used to arrest a number of high profile critics of the conflict. Despite these efforts, public opinion was by no means pro-war: When the US government asked for one million volunteers at the start of the war, only 73,000 people signed up in the first six weeks. The government had to start drafting people to meet their quota. In addition, the Socialist Party—the main anti-war party—made significant gains in state and local elections during the war.

World War II (1939-1945)

In 1939, World War II began between the Axis Powers, led by Nazi Germany, fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan, and the Allies, led by the UK, France, and the USSR. The US joined the Allies two years later. However, Zinn argues that American participation in the war was less about fighting fascism and more about protecting imperial power and elite financial interests. He offers several pieces of evidence: First, the US didn’t fight fascism in the years leading up to the war, whether in the Spanish Civil War or during the gradual rise of Nazi Germany. Second, the US didn’t join the war until its imperial possessions were directly attacked.

Regardless of this elite reasoning, popular opinion in the US was mostly pro-war. Many Americans supported the allied cause due to patriotism and anti-Japanese racism. While some Black Americans didn’t want to fight for their oppressors, many others were drafted or voluntarily joined the prejudicial and racially segregated US military. Despite the overall pro-war sentiment, though, the US government still suppressed any perceived dissent—using the Espionage Act to arrest anti-war activists and imprisoning thousands of Japanese Americans in internment camps, even if they supported the American war effort or had no connections to Imperial Japan.

Post-War Settlement

As the major power who’d suffered the least damage during the war, American elites were able to dictate a favorable post-war political and economic landscape, explains Zinn. They did so in a number of ways: funding massive reconstruction programs in Western Europe through the Marshall Plan, granting the US a significant amount of control over the newly formed United Nations and International Monetary Fund, and securing oil for decades to come through an alliance with the Saudi royal family.

Because of this uncontested economic position, enough money was flowing into the country that elites were willing to provide benefits to many American workers and laborers. The GI Bill provided funding to help thousands of veterans buy homes and attend college. Infrastructure projects, anti-poverty initiatives, and cheap goods caused overall standards of living to rise. At the same time, however, military, business, and political elites collaborated to ensure the existing war economy would continue indefinitely, concentrating disproportionate wealth in their hands.

The Cold War (1947-1991)

Following the end of World War II, Zinn explains, American elites embarked on a decades-long campaign to prevent the spread of communism and protect their—and Western European elites’—financial interests. This strategy would limit the political and economic strength of the Soviet Union while also protecting the US-dominated post-war economy. Zinn notes several important theaters of the Cold War, including the CIA’s covert operations and the Vietnam War.

Covert Actions and the CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency, or CIA, covertly enacted America’s foreign policy throughout the Cold War. Composed of a number of business and political elites, the CIA supported, planned, and even participated in coups in countries that threatened American or European business interests—regardless of whether they were communist or pro-Soviet. For example, the CIA helped coordinate a coup of the democratically elected leader of Iran, Mohammad Mosaddegh, when he attempted to nationalize the country’s British-owned oil companies.

The Vietnam War (1963-1972)

In some instances, Zinn explains, covert actions weren’t enough to secure the goals of elites. This was the case in Vietnam, where the US tried and failed to covertly stop popular Vietnamese resistance against the French colonial government. Instead of trying to work with the initially cooperative Vietnamese revolutionary movement, the US created a capitalist dictatorship in South Vietnam and eventually went to war with North Vietnam to defend it. During the war, the US used a strategy of mass death and destruction—using chemical and incendiary weapons to destroy wildlife, bombing civilian infrastructure like dams to cause starvation, and indiscriminately killing civilians.

From the mid to late ’60s, the anti-Vietnam War movement became a popular force across the US. Black Americans in the Civil Rights Movement started the campaign, but thousands of students, young people, and eventually the middle class joined. Civilians protested and dodged the draft, while anti-war American soldiers deserted, refused to follow orders, or even killed their commanding officers in protest. Faced with mounting domestic political pressure and a determined, skilled North Vietnamese insurgency, US elites eventually had to admit defeat. They withdrew American soldiers from Vietnam, and South Vietnam collapsed shortly afterward.

Social Upheaval and the Modern Consensus (1945-2001)

Zinn explains that, while the post-WWII settlement and spoils of empire made the US richer than ever before, it didn’t resolve the social unrest of previous decades. If anything, the influx of wealth further revealed the country’s many inequalities and social divides—inspiring decades of popular social movements for justice and equality. Despite these efforts, elites cemented control over political and economic institutions, creating a “modern consensus” in politics that persisted into the 21st century.

Social Movements (1945-1980)

Zinn outlines several of the significant social movements of the ’40s through the ’70s: the decline of the labor movement during the Second Red Scare, the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements, second-wave feminism, and more.

The Second Red Scare (1945-1960)

In the years following WWII, elites purged members of left and labor movements in the Second Red Scare, explains Zinn. Seeing the rise of the communist bloc, the start of decolonization, and a strike wave in the US once the no-strike pledge ended, elites feared the possibility of a strong American left. They responded with mass firings, prosecutions, and investigations of leftists and labor activists under the guise of combatting the Soviet Union and communism. They also passed laws limiting the power and influence of unions. Zinn argues the Second Red Scare started the decline of the American labor movement, as organizations either cooperated with purges or had their influence reduced via legislation.

The Civil Rights and Black Power Movements (1954-1980s)

Despite Black participation in WWII and the booming post-war economy, Black Americans remained a legally segregated and oppressed underclass, Zinn explains. As a result, Black Americans organized on a larger scale than ever before to struggle for equality. Their struggle began with the Civil Rights Movement, a campaign for legal equality through peaceful, yet disruptive protests. From 1954 to 1968, the Civil Rights Movement pressured elites into outlawing racial segregation and passing a series of moderate reforms to protect Black rights.

However, Zinn argues, legal equality failed to significantly improve the lives of Black Americans, as racial discrimination, racist violence, and poverty were still commonplace. As a result, some Black Americans embraced the more radical and militant beliefs and methods of the Black Power Movement. Through leaders like Malcolm X and Huey Newton and groups like the Black Panther Party, the Black Power Movement advocated the use of violence in self-defense, class struggle, and achieving Black economic and political independence.

Violent white supremacist suppression prevented the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements from achieving genuine racial equality, Zinn argues. Police and white supremacist vigilantes like the Ku Klux Klan murdered and terrorized protesters and activists. Black leaders like Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X were assassinated under mysterious circumstances, while others like Fred Hampton were explicitly assassinated by the FBI. Discriminatory anti-crime measures and the proliferation of drugs destroyed Black communities and their ability to organize, while increased media and political representation of Black Americans gave the false appearance of equality.

Other Significant Movements (1960s-1970s)

Zinn notes there were many other social movements in the ’60s and ’70s on behalf of the vulnerable and oppressed. The second-wave feminist movement, Red Power movement, gay liberation movement, and prison reform advocates sought to raise awareness of injustices and address unequal treatment of women, American Indians, homosexuals, and convicts, respectively. More broadly, movements and the culture of this era challenged conservative social attitudes of previous decades—beliefs about how to approach sex, relationships, work, and so on.

Disillusionment and Scandal (1972-1975)

Zinn suggests the social discontent of the ’60s transformed into distrust of and alienation from politics in the early ’70s. Average Americans didn’t feel like they could impact change: the Vietnam War had lasted almost a decade despite its unpopularity, and political institutions didn’t significantly change even after major scandals. In the Watergate scandal, several of President Richard Nixon’s illegal political operations became public—and while Nixon eventually had to resign, he was never prosecuted and no significant anti-corruption measures were passed afterward.

A group of senators formed the Church Committee to uncover many past illegal CIA operations, coups, and assassinations for the first time—but the agency wasn’t dissolved or even significantly limited as a result.

The Modern Consensus (1974-2001)

Zinn argues that, after the tumultuous ’60s and early ’70s, elites tightened their control over the country. In large part as a consequence of diminished labor power and elite suppression of dissenting social movements, a modern “consensus” emerged in American politics: That is, regardless of party, all American politicians had the same overall political goals.

Lacking alternatives to this consensus and already distrustful of the government after Vietnam and Watergate, Americans became more disconnected from and disinterested in politics. Zinn briefly outlines the main tenets of the modern consensus:

The Modern Consensus on Domestic Policy

In domestic politics, the modern consensus secured the power of corporations and the security state at the expense of the poor and disenfranchised. Economically, this meant deregulation of corporations, weakening labor power, and dismantling the social safety nets of the New Deal and post-war eras. As a result of these policies, levels of inequality and poverty rose. Desperate and lacking organized ways to express discontent, many poor Americans turned to crime. Elites blamed the country’s problems on these criminals and massively expanded the police and prison systems, issuing harsh penalties for minor crimes.

The Modern Consensus on International Policy

Zinn explains that the modern consensus continued the postwar era’s imperial policies—covertly organizing coups, backing dictators, and fighting wars to protect elite business interests. Though America’s “war economy” had ostensibly been for fighting the Cold War, it continued even after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Not wanting to risk Vietnam War levels of public backlash, American elites tended toward smaller and shorter conflicts that were less disruptive to average citizens.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Howard Zinn's "A People's History of the United States" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full A People's History of the United States summary:

- A bottom-up view of American history focusing on the people, not the politicians

- How Indigenous people, Black Americans, women, laborers, and activists lived

- Why social movements of the 60s and 70s failed to create lasting change