This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Where Good Ideas Come From" by Steven Johnson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Why did it take so long for the invention of the computer to take hold? How can different people, working independently, come up with the same innovation?

Good ideas don’t materialize miraculously from nothing. Instead, they build on existing knowledge and ideas. Emergence from the adjacent possible, Steven Johnson argues, is a hallmark of the most successful ideas.

Keep reading to learn what the adjacent possible is and how we can mine it for good ideas.

The Adjacent Possible

Platforms of knowledge shape the realm of the adjacent possible. The adjacent possible, Steven Johnson explains, is a theory developed by Stuart Kauffman that refers to the realm of new ideas that are within reach based on society’s current available information, resources, and abilities. While good ideas can come from outside the adjacent possible, all successfully implemented ideas come from within it.

Ideas developed in the adjacent possible are understandable and achievable at the time they’re created. Those that are developed outside the adjacent possible may be great ideas, but a lack of knowledge or resources makes them unachievable at the time they’re created. Such ideas fail but may be developed later when the needed resources become available.

(Shortform note: Kauffman developed his theory of the adjacent possible specifically in reference to evolutionary biology, while Steven Johnson is noted for applying the theory to innovation and idea generation. Kauffman also added that the number of possibilities in the adjacent possible increases exponentially with each new development, as each of those developments comes with a huge range of possible further developments that continue to build on each other and create a massive web of potential.)

To explain the adjacent possible, Johnson discusses the work of the inventor Charles Babbage. In the 1830s, Babbage developed the idea for what would have been the first-ever programmable computer. Because of the resources and knowledge available to him, the computer would have been made entirely of mechanical parts and would have been incredibly slow if he had managed to build it. The idea failed because it was outside the realm of the adjacent possible. But, a century later, our cumulative knowledge and resources had widened the adjacent possible to encompass this invention, and modern computers were then developed using the same basic blueprints that Babbage had created.

(Shortform note: In a TED Talk, Johnson adds further context to Babbage’s invention and the platforms that led to it and argues that invention often comes not from necessity but from a sense of playfulness. He explains that the origins of the programmable computer can be traced back to the invention of the flute thousands of years ago. This invention that created sound by blowing air through a tube led to the organ, which used a keyboard to produce such sounds and, hundreds of years later, was adapted into the keyboard of a typewriter. The organ also led to the invention of the music box, which was programmable in the same way Babbage’s computer was—you could swap out the box’s cylinder with the musical “code” on it to make it play a new song.)

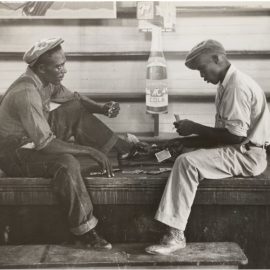

The idea of the adjacent possible helps explain the phenomenon of “the multiple.” This is a historical trend in which the same novel idea is discovered by multiple people working independently of each other. For example, two separate inventors, Dean Von Kleist and Cuneus of Leyden, both invented the electrical battery separately within one year of each other in the mid-1700s. If different people are working from the same knowledge base, then the realm of possibilities for their work will be similar, even if they aren’t working together, because they’re all limited to the base knowledge’s adjacent possible.

| Alternative Theories to “The Multiple” and the Invention of the Battery The multiple stands in contrast to the heroic theory of invention discovery, which is the belief that new ideas and innovations are the result of moments of brilliance by heroic figures acting in isolation. This theory discounts the existence of platforms and the adjacent possible in favor of the exaltation of specific inventors, but historical evidence more strongly supports the theory of the multiple. However, Johnson’s assertion that Dean Von Kleist (who is more commonly referred to as E. Georg von Kleist) and Cuneus of Leyden (who, in turn, is more often known as Pieter van Musschenbroek) invented the battery isn’t quite accurate: They invented what’s now called the Leyden jar, which is a precursor to the battery. Still, the fact that the Leyden jar was later used by Benjamin Franklin in his famous kite experiment and by Alessandro Volta, who is commonly credited with building the first battery, reinforces Johnson’s argument that all innovations build on previous knowledge. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Steven Johnson's "Where Good Ideas Come From" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Where Good Ideas Come From summary:

- How the world's best inventions grow from minor inklings

- How capitalism negatively impacts innovation

- Why making mistakes is essential to great innovations