This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "And There Was Light" by Jon Meacham. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What’s the difference between abolition and emancipation? Why didn’t Abraham Lincoln support a federal mandate to free slaves?

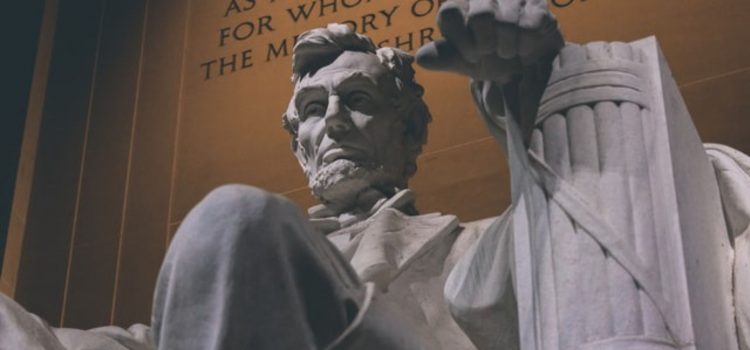

In And There Was Light, historian and biographer Jon Meacham discusses Abraham Lincoln’s stance on slavery. He explains where Lincoln’s beliefs came from and the actions he took in an effort to end the practice in the United States.

Read more to learn about the Great Emancipator’s views and actions in relation to slavery.

Abraham Lincoln’s Stance on Slavery

Jon Meacham’s discussion of Abraham Lincoln’s stance on slavery begins with Lincoln’s childhood and culminates in the Emancipation Proclamation. Let’s dive into the details.

The Forging of Lincoln’s Convictions About Slavery

In 1816, Lincoln’s family moved north to a settlement in Spencer County, Indiana, called Little Pigeon Creek. They moved to Little Pigeon Creek because his father could buy land much more cheaply in that area. This also moved the Lincolns to an area where the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 had made slavery illegal. So, Lincoln spent this part of his childhood in an abolitionist culture, a place where most people favored outlawing (abolishing) slavery.

(Shortform note: It’s common to think of supporting slavery versus abolition as a purely moral or political issue, but understanding why so many people in the South supported slavery requires looking at the economic issues as well. The southern US was largely agrarian and relied on huge plantations to sustain local economies. Without the automated farming equipment we have today, plantation owners felt they needed enormous amounts of cheap labor to grow and harvest their crops, and slavery was their solution. This is not to say that all Southerners supported slavery—nor that all Northerners opposed it—but the trends do largely follow these economic differences.)

In addition to shaping his morality, Lincoln’s religious upbringing influenced his political views. Many Baptists opposed slavery, and abolition was a common topic in conversations and sermons.

(Shortform note: Though laypeople often use the terms interchangeably, abolition and emancipation are not the same thing. Abolition means outlawing the entire practice of slavery, while emancipation specifically means freeing enslaved people. To highlight the difference between the two, consider a hypothetical situation where enslaved people are emancipated but slavery isn’t abolished: Enslavers would have to free the people they currently enslave, but it would still be legal for them to buy or enslave new people.)

Furthermore, the Lincolns belonged to a religious organization called the Baptist Licking-Locust Association Friends of Humanity, which was dedicated to emancipation—in other words, freeing all enslaved people in the US.

(Shortform note: There wasn’t an official Baptist stance on slavery during Lincoln’s childhood. However, there was a strong anti-slavery sentiment among many Baptists, as evidenced by organizations like the Friends of Humanity, which would not accept enslavers as members. In 1845, the growing schism between Baptists who supported slavery and those who favored emancipation led to the Southern Baptist Convention breaking away from the main body of Baptists. However, the Southern Baptist Convention officially denounced and apologized for its racist history in 1995.)

Lincoln Begins Confronting Slavery

Meacham says that slavery versus emancipation was one of the biggest, if not the biggest moral and political question of Lincoln’s lifetime. Lincoln was a member of the Whig Party, which opposed slavery but believed that the federal government didn’t have the power to abolish it. Therefore, Lincoln favored a gradual cultural shift instead of a federal mandate to free enslaved people. He and his colleagues hoped that, as more and more states voted to emancipate their enslaved residents, the states that still favored slavery would feel increased political pressure to abolish it as well. In this way, all enslaved people could eventually be freed without the risk of the federal government overstepping its Constitutional powers.

(Shortform note: The separation of state and federal powers is a key part of the US Constitution, but it’s also the source of a great deal of debate regarding exactly what the federal government can do. The Constitution only explicitly grants the federal government a few powers, such as the ability to declare war. However, it also contains a clause allowing the federal government to pass any laws necessary to carry out those listed functions. So, while the Whigs were correct that abolishing slavery wasn’t explicitly within the power of the federal government, a more expansive interpretation of the Constitution would allow it if legislators decided that ending slavery was in the country’s best interests—which Lincoln himself would later do with the Emancipation Proclamation.)

Lincoln also served a single term in the US House of Representatives from 1847 to 1849. In 1849, in his role as a representative of Illinois, Lincoln proposed a resolution that would eliminate slavery in just Washington, D.C. He put forward a moderate plan, which he hoped would free enslaved people without upsetting enslavers too much—for example, the resolution required enslavers to be compensated for the full value of any enslaved people they freed.

However, Lincoln’s plan was almost universally rejected. Abolitionists thought he was being too generous to enslavers, while slavery advocates were against any proposal to abolish it. For the first time, Lincoln’s centrist approach to politics failed him.

(Shortform note: The failure of Lincoln’s 1849 proposal was likely the result of Lincoln trying to find a middle ground between two diametrically opposed groups (abolitionists and enslavers). In fact, it was just one of several compromises that Congress considered, all of which either failed to pass or failed to appease both sides. For example, the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act—which added those two states to the Union—tried to skirt the slavery issue by letting residents of the new states vote on whether slavery would be legal. However, this led to years of violence in Kansas, as pro-slavery and anti-slavery groups clashed over whether Kansas would be a free state or a slave state.)

Backlash to Lincoln’s Election Win: 1860-1861

Lincoln, as well as the Republican Party as a whole, strongly opposed slavery. Therefore, Lincoln’s presidential election win in 1860 pleased abolitionists, but he and his colleagues feared retribution from slavery advocates. In fact, Meacham notes, there were rumors that former Virginia Governor Henry Wise was raising an army of 25,000 men, with a plan to march on Washington, D.C., and stop Lincoln from taking office. The rumors of an attack on Washington, D.C. proved false; instead, the pro-slavery South decided to leave the Union entirely.

The American Civil War: 1861-1865

Meacham says that, during the Civil War, Lincoln wondered whether God would favor the Union or the Confederacy. In other words, Lincoln came to view the war as a religious and moral struggle, not just a military one; he believed God would ensure victory for whichever side was morally right.

| What Caused the Civil War? While it’s commonly believed that the Civil War was purely about slavery versus emancipation, Lincoln stated that his one and only goal in the war was to preserve the United States by preventing the Southern states from seceding. It was only with the Emancipation Proclamation—which we’ll discuss shortly—that Lincoln shifted his focus to freeing enslaved Southerners. In fact, Lincoln’s determination to keep the US united was so strong that, even as the Confederacy prepared to attack Fort Sumter, he still hoped to avoid all-out war. Despite knowing that the Confederates were targeting Fort Sumter, Lincoln opted to defend it only by sending supplies on unarmed ships, rather than taking any overtly hostile action such as sending troops or weapons. However, South Carolina’s representatives had declared that any attempt to support Fort Sumter would be a declaration of war against the Confederacy. Therefore, while the attack on Fort Sumter is now considered the official beginning of the Civil War, Confederates argued that Lincoln himself was responsible for starting it. |

The Emancipation Proclamation: 1863

On January 1, 1863, two years into the Civil War, President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation into law. By doing so, he officially freed all enslaved people in Confederate states—though, as Meacham points out, not those in the few Union states where slavery was still legal.

Meacham adds that Lincoln’s decision to finally sign the Proclamation wasn’t driven only by morality. The Union was struggling in the Civil War, and Lincoln hoped that emancipation would encourage more Black Americans in the North to join the fighting, thereby bolstering the Union’s ranks. His gambit worked, and as a result, the Union gained a decisive edge.

(Shortform note: Lincoln didn’t sign the Emancipation Proclamation only out of desperation for more soldiers, but because the Civil War gave him legal grounds to free the slaves. As Doris Kearns Goodwin explains in Leadership: In Turbulent Times, Lincoln still held to his belief that the federal government didn’t have the authority to outlaw slavery—however, by utilizing the special wartime powers granted to the president, Lincoln was able to get around that constraint and sign the Proclamation. This is also a possible explanation for why he didn’t free the slaves in Union states; since he wasn’t at war with those states, he had no grounds to use special wartime powers to end slavery there.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Jon Meacham's "And There Was Light" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full And There Was Light summary:

- The myths and legends that surrounded Abraham Lincoln

- Abraham Lincoln's life in chronological order, from his birth to his assassination

- What the Republican Party looked like in the 19th century