This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Lincoln on Leadership" by Donald T. Phillips. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What was Abraham Lincoln like as a leader? What lessons can modern-day leaders draw from Lincoln’s leadership?

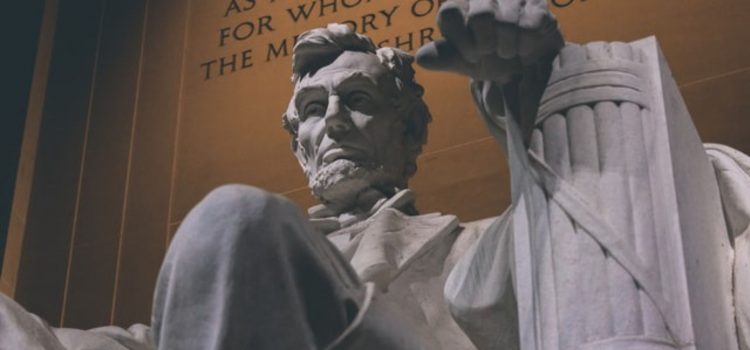

Abraham Lincoln is hailed as one of the greatest leaders in the history of America. But even leaders such as Lincoln can’t accomplish great things on their own. To a large extent, Lincoln owes his success to his ability to make allies through his open and empathetic communication style.

In this article, we’ll explore two communication lessons modern leaders can learn from Lincoln’s leadership.

Lesson #1: Make Yourself Accessible

Phillips argues that leaders should be open, accessible, and friendly to the people around them. This includes being around if people want to talk to you, as well as having a friendly and welcoming demeanor. By making yourself easy to approach and listening to your employees, you’ll gain their trust and respect—they’ll see that you care about their opinions and are committed to working alongside them. In addition, by talking to people on every level of your organization, you can gain valuable information about how things work and how you could improve them. This information can then help you make well-informed decisions later on.

Phillips writes that Lincoln practiced these principles throughout his presidency, going out of his way to be accessible. Lincoln accomplished this by spending a lot of his time talking with others—from high-ranking generals and politicians to common soldiers and farmers. He’d frequently visit people where they lived or worked and had an “open-door” policy where people could come talk to him at any time. In addition to meeting lots of people, Lincoln also made himself accessible through his demeanor and rhetoric: He was friendly, had a good sense of humor, rarely gave harsh commands or orders, and used clear and simple language to connect with whoever he talked to.

(Shortform note: Though Phillips and other scholars praise Lincoln’s accessibility and “man of the people” attitude, the president’s public availability wasn’t without its risks. Confederate spies (who either worked directly for the Confederacy or were just sympathizers) were commonplace in Washington, D.C.’s political and social scenes. By making himself available to the public (despite the protests of those close to him like Union spy Lafayette C. Baker, who was concerned about Lincoln’s safety), Lincoln often put himself in danger—danger that turned out to be very real when he was assassinated in 1865.)

Lesson #2: Build Strong Relationships

In addition to traveling and meeting lots of different people, Phillips suggests that you put extra effort into building strong relationships with the people working directly underneath you. By getting to know them personally as well as professionally, you can eliminate misunderstandings and find common ground with your subordinates—even those who might initially dislike you or disagree with your views. Once you’ve built these relationships, those directly under you will also learn to understand you and what you want. This means they’ll do better work and won’t need as much (if any) oversight from you.

(Shortform note: While Phillips focuses on getting close to your existing employees, Jim Collins (Built to Last) claims that the process of building close ties with your employees starts before they’re hired. Collins explains that during your hiring process, you should look for people who agree with the core philosophy of your organization—how you see the world and what you’re trying to accomplish. By screening for similarly-minded people, you’ll hire employees who are more invested in you and your organization because they believe in it. For example, Collins notes how the Walt Disney Company uses its hiring and onboarding processes to teach its company philosophy and ensure that employees believe in that philosophy.)

As a leader, Abraham Lincoln was personable and accessible. He would often personally get to know his closest advisers, generals, and political allies. He’d visit their homes and meet their families to try to get a sense of who they were. This helped Lincoln understand the viewpoints of his allies and how he could best use them. Lincoln was even able to build relationships with some of his former political rivals or those who disagreed with many of his policies.

Similarly, Lincoln would often personally get to know his closest advisers, generals, and political allies. He’d visit their homes and meet their families to try to get a sense of who they were. This helped Lincoln understand the viewpoints of his allies and how he could best use them. Lincoln was even able to build relationships with some of his former political rivals or those who disagreed with many of his policies.

| Building the “Team of Rivals” Lincoln famously invited many of his former political opponents to join his cabinet—a group that came to be known as the “team of rivals.” Doris Kearns Goodwin (Team of Rivals) discusses why Lincoln chose cabinet members who disagreed with him—and how he overcame these differences. Goodwin suggests that Lincoln built his team of rivals to represent a broad spectrum of political views during an intensely polarized and contentious period. By doing so, he hoped to not only appoint skilled and capable politicians but also to unite an uneasy country behind his leadership. Lincoln appointed rivals within his own party (like William H. Seward and Salmon P. Chase, both of whom had stronger anti-slavery views than Lincoln) as well as former members of the opposing Democratic Party (like Gideon Welles and Montgomery Blair, both of whom began their political careers as Democrats before leaving the increasingly pro-slavery party). Lincoln also balanced his cabinet geographically, with members from the East Coast, the Midwest, and Southern border states like Missouri and Maryland. In addition, Goodwin describes how much of Lincoln’s initial relationship-building focused on appeasing the dignity and pride of his potential cabinet members—especially those who had just lost the party nomination or election to him. These early stages consisted of Lincoln being both kind and stern—he’d compliment the skills and importance of his appointees but would also put his foot down when they tried to dictate how he ran his cabinet. Due to the range of beliefs within the “team of rivals,” Lincoln often had to use his personal relationships with these men to defuse their conflicts. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Donald T. Phillips's "Lincoln on Leadership" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Lincoln on Leadership summary:

- A look at what Abraham Lincoln did and how he did it

- Leadership lessons you can learn from Lincoln

- Why you should consult together and decide alone