This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Freakonomics" by Steven Levitt and Stephen Dubner. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Why We Falsely Link Effects to Causes

When two things happen together, it’s tempting to believe that one caused the other. For example, in the previous chapter, we saw that the economy improved while crime rates dropped. This seems like a satisfying explanation, until the data show the economy couldn’t have had a large effect.

In reality, many correlated phenomena are correlated purely by chance. This gives rise to the well-known saying, “correlation does not imply causation.”

(Shortform note: this underlies a lot of popular superstitions, like people who wear their “lucky hats” to baseball games because they think it helps their team win.)

How Parents Fall Prey to the Correlation vs. Causation Trap

A great demonstration of the correlation/causation trap can be found in the proliferation of popular theories about how “best” to raise children. For years, childcare experts have advocated contradictory and ever-changing theories:

- They used to advocate co-sleeping—now they don’t.

- They used to encourage stomach-sleeping for infants—now, since we know so much more about sudden infant death syndrome, they REALLY don’t.

Because the stakes are so high, parents are highly susceptible to fearmongering and conventional wisdom on childcare. Unfortunately, this leads parents to go to extraordinary lengths and expend vast resources on measures that have a questionable impact on child safety. They purchase expensive car seats, despite their dubious safety record. They forbid their children from playing at homes where guns are present, while ignoring more mundane, but far more likely risks like unfenced pools.

In general, we tend to fear things that seem random, sudden, and unpredictable (even if they are wildly unlikely). It’s why we demand action against terrorism (which you stand almost a zero percent chance of falling victim to), but are blasé about heart disease (which kills over 600,000 Americans annually). It’s why we panic over mad cow disease (a similarly low risk), while being relatively sanguine about global warming (a slow-moving catastrophe that nevertheless threatens to destroy civilization as we know it).

So do parents need to worry as much as they do? Do our efforts as parents even make as much of a difference as we think they do?

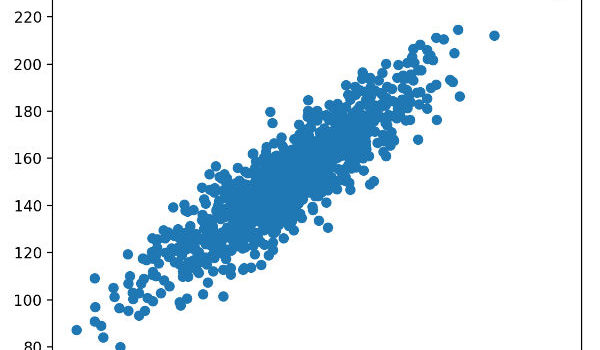

Regression Analysis: Breaking Down the Correlation vs Causation Fallacy

The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS), launched by the US. Department of Education in the 1990s, measured the academic progress of over 20,000 students as they progressed from kindergarten to the fifth grade, interviewing parents and educators and asking a broad range of questions about the children’s home environment. The study provided an ample resource of data that researchers could use to identify more statistically meaningful relationships between specific parenting tactics and children’s academic outcomes – teasing apart correlation vs causation.

Researchers used regression analysis to draw conclusions from this rich data set. Regression analysis enables researchers to isolate two variables in a complicated and messy set of data, holding everything else constant to identify relationships between variables. Its main benefit is that it allows analysts to control for confounding variables that might otherwise confuse the true causal relationship.

It is important to note that regression analysis does not “prove” causal relationships or answer the correlation vs causation question. The only way to truly do that would be to set up a randomized, controlled experiment, similar to what would be done in a clinical trial for a new pharmaceutical. This is very hard (if not impossible) to do in a field like economics, where it is highly impractical to create these conditions. Thus, economists use regression analysis to study causative relationships in natural experiments.

According to the ECLS study, these are the factors that were strongly correlated with children’s test scores:

- Having highly educated parents

- Having parents with a high socioeconomic status

- Having a mother thirty or older at the time of her first child’s birth

- Being born with a low birthweight

- Speaking English in the home

- Being adopted

- Having parents active in PTA

- Living in a home with many books

Meanwhile, these factors were not correlated with children’s test scores:

- Coming from a traditional, two-parent home

- Moving to a better neighborhood

- Having a stay-at-home mom between birth and kindergarten

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Freakonomics" at Shortform c . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Freakonomics summary :

- How every single person behaves according to incentives

- Why you should tune out experts and make your own decisions

- The surprising truth behind why crime declined so much in the 1990s