This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "What You Do Is Who You Are" by Ben Horowitz. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Does your company culture need improvement? If so, where should you start? What practical steps can you take to make lasting change?

In the book What You Do Is Who You Are, Ben Horowitz shares three cultural leadership lessons taken from the story of Shaka Senghor. Senghor demonstrated transformational leadership when he served in prison. Horowitz discusses three lessons from Senghor’s story: take advantage of teachable moments, start necessary changes from the top, and meet daily to model changes.

Keep reading to learn how to improve company culture.

How to Improve Company Culture

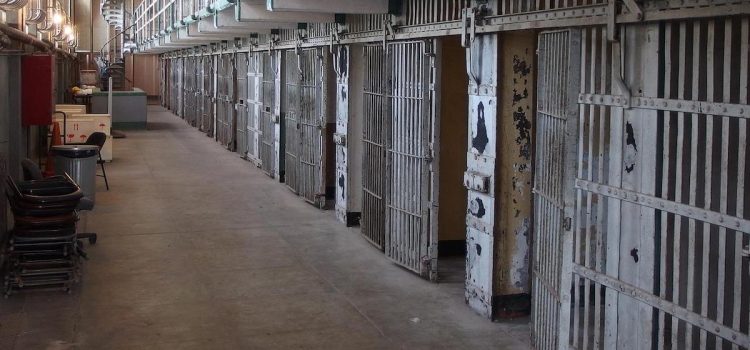

Detroit-native Shaka Senghor’s path to cultural leadership began the day he arrived at prison for committing murder in a street conflict. Ultimately, he became a force for good inside the prison system by continuously assessing and improving the culture of the squad, or gang, he belonged to. He did this by reading and educating himself and squad members on self-improvement and Black leadership. He also became a leading criminal justice reformer after his release.

(Shortform note: Senghor’s path is an example of servant leadership, a model in which the leader puts the well-being of followers first. To become a servant leader, there are several critical behaviors to apply:

- Using your experience and resources to help solve problems

- Being supportive of followers and listening to their feelings and concerns

- Making followers a priority and empowering them to grow and succeed

- Behaving ethically and having a positive impact on the larger community)

Horowitz believes that cultural leaders in the business world can learn how to improve company culture by following Senghor’s example of critically analyzing their own culture so they can improve it over time. To be sustainable, cultures must adapt, let go of rules or virtues that no longer serve the organization, and incorporate new ones that do. We’ll discuss three lessons Horowitz learned from Senghor, as well as examples from the business world.

Tip #1: Take Advantage of Teachable Moments

Senghor’s first teachable moment in prison was seeing a man casually stab another in the neck on his way to the cafeteria—the incident taught him the cultural rules he needed to know to survive in his new environment. He understood he needed to be decisive and courageous, and he also realized that he was willing to use violence to defend himself if necessary. (Shortform note: That teachable moment was also illustrative of what life in prison is like in the US. According to data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics, state prison deaths rose 44% from 2001 to 2018, while prison population has only increased by 1%.)

Similarly, to make sure employees internalize a cultural rule or virtue, Horowitz advises that you find a concrete—but nonviolent—way to bring it to life. Especially after someone has broken a rule or disregarded a cultural virtue, breaches can become teachable moments that make it clear why a certain behavior is unacceptable and what the consequences of that breach will be. But Horowitz says your approach to these moments must be cold-blooded to work so that the message is loud and clear.

(Shortform note: Clay Christensen, author of How Will You Measure Your Life, agrees that it’s important to respond decisively when a breach happens. He argues that it’s easier to maintain your standards 100% of the time than 98% of the time, because once you’ve committed a minor transgression, you fall down a slippery slope of ever-increasing rule-bending and breaking.)

Tip #2: Start Necessary Changes From the Top

When Senghor realized his squad valued violence over any other method of conflict resolution, he acknowledged his own double standards. He had been educating himself on alternatives to violence, but he still encouraged his squad to follow the regular rules of prison culture. He realized his approach to leadership needed to change, because his members would take that violence with them when they left prison. So he shifted the culture of the squad in a more positive direction, and after leaving prison, he became a prison reformer, author, and a cultural leader for a broader population.

(Shortform note: Senghor’s experience highlights the complex role of gangs in the prison ecosystem. While gangs use violence to exercise their power, they can also contribute to the decrease of violence by exercising control over their members.)

In the same way that Senghor underwent a personal transformation before he was able to transform the Melanics, Horowitz argues that when something in the culture needs to shift, the change needs to start with the leader. You set the tone for the culture, even if your example doesn’t reach every one of the organization’s members. If you set the right example, people have a concrete example to follow, and both your words and deeds communicate the organization’s priorities.

(Shortform note: In The Leadership Challenge, James Kouzes and Barry Posner lay out detailed guidelines for creating and setting a new example for an organization:

- First, establish your values and communicate them to the team. Then, help your team align their own values by proactively engaging in conversations about them.

- Next, model your values by embodying them constantly, including through your calendar, agenda, and the language you use.)

Example: Question Your Own Ethics

When Horowitz was CEO of LoudCloud, he had to acknowledge his own faults to improve the culture. As the company prepared reports on the quarter’s revenue and contracts, they found that, although revenue was good, they didn’t have many contracts signed for the next quarter. They worried their lack of contracts would get bad press coverage, which would lead to customers not signing contracts, and finally to having to lay people off as a result of the reduced revenue.

Someone on the team suggested reporting revenue and contracts together so the low number of contracts wouldn’t be obvious. Horowitz was considering the suggestion until their legal counsel spoke up against it, arguing that making the report purposely confusing might have been legal, but the move was still dishonest. It was a wake-up call for Horowitz, who had been willing to engage in the behavior. To keep himself and his team from treading into murky waters in the future, he redefined an existing company virtue from “telling the truth” to “making sure people hear the truth.”

(Shortform note: This anecdote shows the importance of nurturing virtues that are achievable and that will steer an organization through difficult times. In his first book, The Hard Thing About Hard Things, Horowitz shares more details on the challenges he was facing. The company started at the cusp of the dotcom bubble, and it was investing heavily on growth right as the bubble burst. Overnight, customers were strapped for cash, which put LoudCloud in the difficult position of having few contracts despite optimistic earlier projections. Eventually, the company rode out the crisis and became Opsware, but not without significant difficulties along the way.)

Tip #3: Meet Daily to Model Changes

To change his squad’s culture, Senghor made sure they all had lunch together every day and used that time to discuss books he had assigned for them to read. They worked out and studied together, and Senghor used every opportunity to reflect on the values he hoped to instill in them. He organized group classes on emotional intelligence so they could understand the trauma that had led them to their current situations.

(Shortform note: Constant interaction is perhaps all the more important in the prison context since squad members can be taken to solitary confinement and be completely isolated for extended periods of time. Senghor himself was in solitary confinement for months and likely understood the importance of human contact in improving individual outcomes since he relied on letters from his family members to make it through those periods of isolation.)

Constant interaction gave him opportunities to discuss and reinforce the cultural changes he wanted to see. According to Horowitz, one way to ensure a team understands the importance of a culture change you’re trying to implement is by getting together every day to discuss the change, model the new expected behavior, and ask for updates on implementation. If you, as the leader, are willing to take time out of your day every day to talk about the change and model the new behavior, it signals to employees that it’s a top priority and they need to get on board with the change.

(Shortform note: Daily interaction on its own might not be enough to support a change in the culture. Experts argue that leaders also need to be intentional in how they communicate during times of organizational change. They can do so by expressing the results they’re after in terms of outcomes and not just tasks, adjusting the way they spend their time to show they are themselves committed to the change, and making sure they assign enough resources to support the change they’re looking for.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ben Horowitz's "What You Do Is Who You Are" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full What You Do Is Who You Are summary :

- The three reasons leaders should care about culture

- How a sense of purpose boosts employees' performance

- What the Samurai and Genghis Khan can teach you about leadership