This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "When the Body Says No" by Gabor Maté. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Does stress cause cancer? How can stress lead to growth of cancerous cells?

In his book When the Body Says No, Dr. Gabor Maté explains that certain cancers result from hormonal changes, and hormones can be affected by stress. Therefore, chronic stress can cause a domino effect, eventually leading to the growth of cancerous cells in the body.

Here’s a look at the link between stress and cancer.

Stress and Cancer

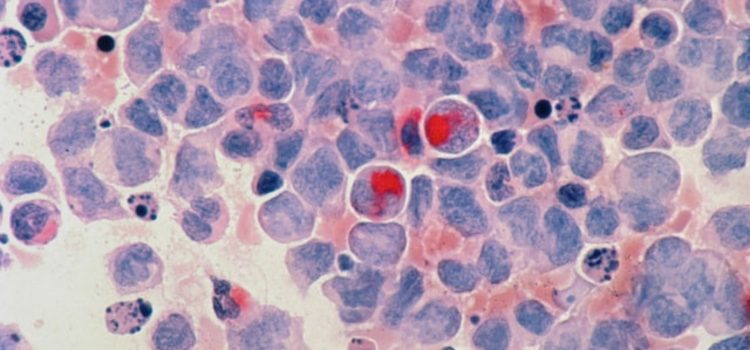

Does stress cause cancer? In looking at cancer, we can see some commonalities in personal characteristics. Maté explains that all humans have damaged and abnormal (even malignant) cells in our bodies. The vast majority never become cancer, however, because the immune system works to repair the damage, or the cells die off before they replicate. According to Maté, this means that for any cancer to occur, cell damage alone is not enough; there must also be some failure of the immune system that allows the damaged cells to continue replicating unchecked.

Maté cites research that shows that stress inhibits immune processes. The PNI (psychoneuroimmunoendocrine) system creates conditions that either facilitate or inhibit the growth of cancer cells, and we know that psychological processes and emotion affect the PNI system. Several studies on psychosocial factors related to cancer have found the biggest risk factor is repressed emotions, specifically feelings of anger.

(Shortform note: As evidence for Maté’s claim that medical research and practice don’t substantially address the psychosocial histories of patients, the comprehensive historical overview of cancer, The Emperor of All Maladies, focuses almost entirely on the biological makeup and treatment of the disease. Although the author does address failure of the immune system as a direct contributor to tumor growth, he does not substantially investigate psychological contributors to immune suppression.)

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and prostate cancer are all hormone-related cancers. Maté describes research in which no link was found between stress and breast cancer, so the conclusion was that there was no correlation. However, Maté raises an important critique that calls this conclusion into question: In the conclusions, it was stated that the risk factors are primarily genetic and hormonal. But, Maté points out that only 7% of breast cancer patients are genetically high-risk, so that can’t be considered a strong link. And perhaps more importantly, it is well-documented that hormones are influenced by stress.

In other research described by Maté, psychosocial factors have been linked to breast cancer, including: emotional distance from parents as children; repression of emotions, especially anger; lack of supportive relationships; and, “compulsive caregiving” tendencies (self-sacrifice). He cites two different studies in which researchers could predict with 94-96% accuracy which women would be diagnosed with breast cancer based only on these psychosocial factors. Similar results have been shown with studies on ovarian cancer.

(Shortform note: A 2001 study of breast cancer patients in China showed that those who scored the highest for positive relationships with spouses, families, and friends had a 38% lower incidence of mortality and a 48% lower incidence of recurrence of the disease than those who had poorer relationships. Additionally, the researchers were surprised by the finding that physical well-being was less important than supportive relationships in the women’s survival and continued health. This effect was strongest in the first year or so after diagnosis.)

Prostate Cancer

Even though it’s known that prostate cancer is inextricably linked to hormones, and hormone balance to stress, Maté says there have been no studies investigating the link between psychosocial factors and prostate cancer. But it has been linked to environmental factors—Black American men are twice as likely to get prostate cancer as white American men. In seeking to explain why this might be the case, Maté says it can’t be racially genetic, because Black American men are six times more likely to get it than men in Nigeria. Therefore, he theorizes that it’s likely due to the social pressures of being a Black man in America, including the chronic stresses of dealing with racism, as well as a lack of community and family support networks that tend to be more common in Black American communities.

| Racial Health Disparities in America A number of health disparities exist between racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Black, Hispanic, and Native American populations are more likely to suffer from chronic diseases, such as cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and asthma. Research hasn’t shown a biological or genetic factor that can account for these disparities, so the cause for this has been attributed to: – Access to health care: Minority groups in America are more likely to live in poverty and therefore have less access to health care. – Poor nutrition: Those groups are also less likely to have access to a healthy, nutritious diet. – Exposure to toxins: Disadvantaged communities are more likely to have poor air quality and housing conditions that could lead to exposure to contaminants, such as lead. – Stress: Not only does poverty create stressful conditions, but daily experience of (or even the anticipation of) discrimination associated with being a person of color in America can cause low-grade chronic stress reactions. |

Lung Cancer

Prevailing theories state that cancers result from damage to the DNA of cells. In the case of lung cancer in smokers, some of that damage is caused by the tobacco product. Maté says that we know this damage happens, but it doesn’t explain why some smokers get lung cancer and others don’t. So, he says, there have to be other factors at play.

Maté cites two different studies that showed a link between lung cancer and repressed emotion, especially anger. Particularly compelling is a long-term study described by Maté that was done in former Yugoslavia. Around 1,400 participants were given extensive medical and psychological testing. Of the 1,400, over 600 were dead 10 years later, at which point the researchers analyzed causes of death along with the psychological profiles. In the conclusions described by Maté, the #1 risk factor for death, especially for cancer, was “rationality and anti-emotionality” (R/A)—meaning those who repressed emotions.

Furthermore, cancer death was 40 times higher in those who scored the highest in the category for repressed emotion. Researchers were able to correctly predict which people would die of cancer in 78% of cases based on just their scores on R/A and feelings of hopelessness. (Shortform note: Since the Yugoslavian study, similar research has been undertaken in Japan, with the opposite findings. In Japan, rationality/anti-emotionality was associated with lower prevalence of all categories of disease. This suggests that there may be a cultural difference at play regarding expectations of emotional display.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Gabor Maté's "When the Body Says No" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full When the Body Says No summary :

- How stress can manifest as chronic illness

- How to heal from and avoid stress-related diseases

- Why toxic positivity can make you sick