This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "Good to Great" by Jim Collins. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is Jim Collins’s “flywheel effect”? Why is the flywheel analogy so important to understand in business?

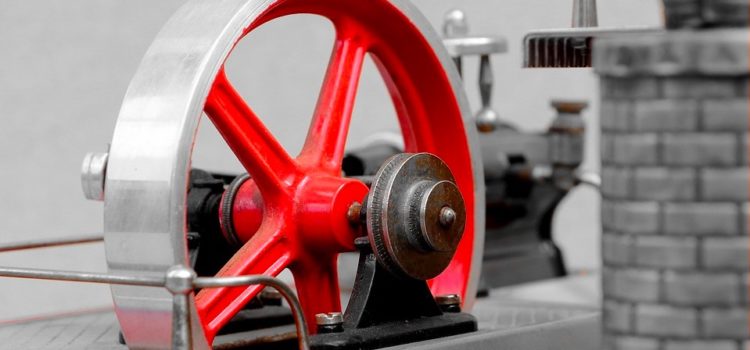

The “flywheel effect” is an analogy between a business and a flywheel. A heavy flywheel takes an enormous amount of energy to get going—but once it’s spinning, it only takes a small amount of energy to keep it turning or to increase its speed. Good-to-great companies achieve their key strengths steadily and doggedly; they stay patient in the confidence that, with the right cogs in place, the breakthrough will come.

Jim Collins’s flywheel effect came from the desire to head off the notion that the features of successful businesses can be implemented or cultivated overnight. Collins elaborates on the flywheel in Good to Great. We’ll cover why the flywheel concept is so important to your business.

Jim Collins’s Flywheel Effect

Top-Line Takeaways

- The “Flywheel Effect” captures the overall feeling of being inside a good-to-great company. To start a heavy flywheel spinning takes an immense amount of hard effort, but once momentum kicks in, it looks unstoppable.

- Even though the results are dramatic, flywheels do not result overnight from one concerted action or one flashy launch or one lucky break. They are the result of a long period of discipline and dedication to a Hedgehog Concept.

- A common excuse of mediocre companies is that Wall Street stifles long-term strategy through its insistence on short-term results. Great companies face the same pressures, but they persist with building their flywheel. The results speak for themselves, earning the grace of Wall Street investors. This is the flywheel effect.

- Whereas the good-to-great companies employed a “buildup phase” that eventually yielded a “breakthrough phase,” the comparison companies attempted to skip the slow work of the buildup with ill-advised acquisitions or other risky moves. With each misguided decision came disappointing results, which further increased the pressure to make bold moves, which resulted in further disappointment—the “doom loop.” This is the opposite of the flywheel effect.

The Feel of the Flywheel

Media accounts of good-to-great success stories are by necessity incomplete—they latch onto the result of a yearslong process rather than the process itself.

For the good-to-great companies themselves, the breakthroughs are far less shocking, because, by dint of the Stockdale Paradox (confronting the facts while keeping faith) and a culture of discipline, those “breakthroughs” seem like the organic outcomes of a transparently obvious strategy. The breakthrough is just the moment when the flywheel starts spinning of its own accord. This is the idea behind Jim Collins’s flywheel effect.

Flywheel Effect Examples: Circuit City and Nucor

Alan Wurtzel, Circuit City’s Level 5 leader, inherited the CEO position from his father in 1973, but the company didn’t receive national recognition until 1984, when Forbes published a feature on its swift rise, portraying it like an overnight success story.

In fact, Wurtzel had inherited a nearly bankrupt company in 1973, and it took every bit of those eleven years for Circuit City to work its way to breakthrough. From rebuilding the executive team to exploring a warehouse-showroom model of retail to favoring consumer electronics over appliances, Wurtzel pursued a fact-driven and carefully paced transition. Success came from the slow process of Good to Great‘s flywheel effect.

Nucor’s buildup, too, was largely ignored by the media. Ken Iverson and his team started revamping Nucor in 1965, and by 1975, the company had built three mini-mills and reimagined its culture. But it wasn’t until 1978 that Business Week published the first major article on the company.

The transformations that turn good companies into great companies don’t have a name or a brand or a tagline—in fact, they’re barely discernible as discrete processes at all. There is no miracle moment. There is, rather, the culmination of the dogged, disciplined pursuit of excellence, the flywheel effect.

That said, to ensure that everyone in their organizations buys into their initiatives, good-to-great leaders make sure they’re communicating each turn of the flywheel—each incremental advance—to their people.

Kroger CEO Jim Herring, for example, when he was leading the supermarket chain’s transformation, created alignment across the 50,000-person company by presenting tangible results to his employees, even if those results were humble. The upshot was that people extrapolated from the smaller accomplishments and got excited about where the company was headed.

The Flywheel Effect and Wall Street

Given analysts’ and traders’ affinity for the quick return, there’s constant pressure on companies to make an impact now rather than later.

But good-to-great companies, featuring disciplined cultures and a stubborn adherence to their Hedgehog Concepts, recognize that greater benefits are to be had from persistent, consistent effort (the flywheel effect) than short-term acquisitions or restructurings that might make a splash in the markets.

Thus good-to-great companies develop mechanisms for managing the short-term pressures from Wall Street. For David Maxwell of Fannie Mae, that mechanism was educating analysts on what the company was doing (i.e., explaining its Hedgehog Concept). He admits that not everyone believed Maxwell’s plan would save Fannie Mae, but as the small triumphs mounted and the results became obvious, Wall Street eventually got on board.

For Abbott Laboratories, the mechanism was a clever deflection tactic built around its long-term objectives.

Flywheel Effect Example: Abbott Laboratories

To mitigate the pressures of the stock market, Abbott would offer middle-of-the-road growth projections to Wall Street, then set internal goals for much higher growth. At the same time, it would maintain a ranked list of new ventures that it had yet to fund, dubbed the “Blue Plans.”

At the end of the year, having exceeded Wall Street’s expectations by reaching or nearly reaching its internal goal, Abbott would release to Wall Street a growth number between the original projected number and the actual one. Abbott would then take the remaining growth funds and channel them into the Blue Plans, thereby simultaneously keeping Wall Street happy and priming the pump for long-term results. This is another example of Good to Great‘s flywheel effect.

The Doom Loop

Rather than hashing out a Hedgehog Concept, evaluating every decision according to it, and advancing their organizations stoically and faithfully, the comparison companies tended to launch flashy new programs in a desperate attempt to build motivation and momentum. They did so reactively and impulsively, without deliberately understanding the key market fundamentals that would increase the likelihood of success. This is the opposite of the flywheel effect.

These programs, because they attempted to skip over the buildup phase and proceed directly to breakthrough, invariably failed: They lacked the necessary foundations to produce sustained results. The failing programs were then replaced by further flashy programs, which met the same fate for the same reason, and the cycle began all over again. Thus: the Doom Loop.

Anit-Flywheel Effect Example: Warner-Lambert (comparison)

Between 1979 and 1998, Warner-Lambert, the direct comparison to Gillette, was led by three CEOs, each of whom instituted drastic changes in direction and philosophy: from consumer products to healthcare and back again and forth again.

These moves were driven by CEO ego—each wanted to make his mark on the company and make big new flashy changes—rather than the diligent use of the three circles.

In the same period, the company underwent three restructurings, laying off 20,000 workers in the process, and its stock returns bottomed out.

Two years later, Warner-Lambert was acquired by Pfizer and ceased to exist as an independent company.

Flywheel Effect: Acquire Deliberately

Acquisitions and leadership changes aren’t intrinsically dangerous—the good-to-great companies featured both in the course of their transformations. But it was the way they used them that spared them the doom loop.

The good-to-great companies executed acquisitions at rates more or less equal to the comparison companies. The good-to-great companies, however, went shopping only after seeing success with their Hedgehog Concept—to turbocharge a flywheel that was already spinning—whereas the comparison companies executed acquisitions to create momentum.

As with technology, great companies use acquisitions as an accelerant, not as a hail-mary pass to save the company.

Lead Consistently

Good-to-great companies also saw leadership changes during their transformations—but, due to Level 5 leaders’ tendency to groom successors (see Chapter 2) and create cultures of discipline (see Chapter 6), transitions from one leader to another were seamless. New leaders at great companies continued to turn the flywheel and accelerated momentum built from the past. Maintaining the flywheel effect involves consistent leadership.

New leaders of the comparison companies, by contrast, had a habit of stopping an already spinning flywheel.

Harris Corporation, for example, recorded great results under two CEOs whose Hedgehog Concept had the company focusing on printing and communications technology. A third CEO, however, moved the company headquarters from its longtime base in Cleveland to Florida (where he had a house) and, shortly thereafter, abandoned the printing business for office automation, giving up one of the most profitable parts of the company for a pipe dream.

Good money flew after bad, and soon enough a company that had been beating the market by more than 5x ended up 70% behind.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "Good to Great" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full Good to Great summary :

- The 3 key attributes of Great companies

- Why it's better to focus on your one core strength than get spread thin

- How to build a virtuous cycle, or flywheel effect, in your business