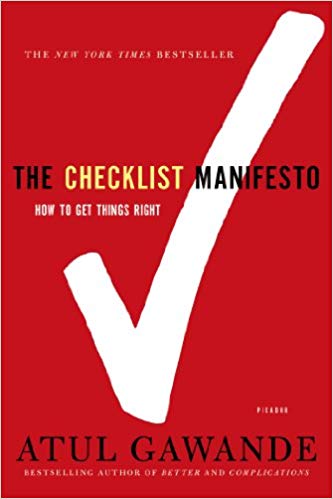

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform summary of "The Checklist Manifesto" by Atul Gawande. Shortform has the world's best summaries of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

In the 21st century, we can do things that were unthinkable not long ago. Yet highly trained, experienced, and capable people regularly make avoidable mistakes. You may be wondering, Why do I make so many mistakes?

After experiencing his own mistakes and observing those of colleagues, Boston surgeon Atul Gawande set out to learn why smart people make avoidable errors and, more importantly, to find a way to prevent them. The result is The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right, in which Gawande proposes a simple solution: a checklist. Learn how to use it to prevent yourself from making avoidable mistakes.

Why Do I Make so Many Mistakes?

Why do I keep making mistakes? In a 1970s essay on human fallibility, Samuel Gorovitz and Alasdair MacIntyre argued that in some cases we fail due to “necessary fallibility” — because we’re trying to do something humans are incapable of. Much of the universe is unknown to us; there are limits to what we can know and do.

Yet we also fail frequently in areas where we have control. Gorovitz and MacIntyre argued there are two reasons:

- Ignorance or lack of knowledge.

- Ineptitude, meaning we have the knowledge, but don’t apply it correctly.

Mistakes due to ignorance can be addressed with more education and experience. But knowledge doesn’t make a difference if we fail to apply it or do so incorrectly. An experienced meteorologist can miss signs of a storm’s likely behavior, or a skilled doctor can forget to ask a patient a critical question.

So, Why do I make so many mistakes? A combination of ignorance and ineptitude…but mostly ineptitude. Luckily, I can do something about this.

Ineptitude in Action

Surgeons like Gawande often tell each other stories of mistakes and near misses, puzzling over how they could have missed seeing something that turned out to be vital. For instance, a surgeon was removing a cancer of the stomach when, about halfway through the procedure, the patient’s heart stopped. The team couldn’t find any cause as they worked to resuscitate him and called for additional personnel and equipment. A senior anesthesiologist who’d been in the room earlier, before the patient had been put to sleep, arrived to help. He asked the attending anesthesiologist if he’d done anything additional since they’d last spoken. The doctor said yes, he’d given the patient potassium when lab reports arrived showing his levels were too low.

When the team dug the IV bag out of the trash, they discovered that the patient had been given the wrong concentration — a lethal dose. Through a variety of heroics, they managed to bring him back. The team was shaken: they’d had all the necessary knowledge and tools, but their ineptitude nearly killed him. Even doctors get things wrong, so don’t beat yourself up when asking yourself, Why do I keep making mistakes?

An Explosion of Knowledge and Complexity

In trying to do the right things, the challenge of the 21st century is ineptitude, rather than ignorance. It used to be the reverse. For most of human history, we struggled with scientific ignorance. We didn’t understand how things worked or what caused illnesses and how to treat them. This answered our question, Why do I make so many mistakes?

But while science has increased our knowledge dramatically, we still often fail. The reason isn’t lack of money, malpractice, or government or insurance issues. It’s the enormous and ever-increasing complexity of many fields today. We struggle to apply knowledge the right way at the right moment. Under pressure, we make simple mistakes and overlook the obvious.

For instance, authorities at all levels make numerous mistakes when disasters strike. Attorneys make mistakes in complex legal cases, most commonly administrative errors. We have foreign intelligence failures, cascading banking industry failures, and software design flaws that compromise the personal information of millions of people. Deciding the right treatment among the many options for a heart attack patient can be extremely difficult. Each one involves complexities and pitfalls.

Getting the right thing done is a challenge too. From research, we know that heart attack patients who will benefit from cardiac balloon therapy should have it within 90 minutes of arriving at a hospital. After that, survival rates drop. But a 2006 study showed less than a 50 percent likelihood that a medical staff could get everything done that needed to be done in less than 90 minutes. Similarly, at least 30 percent of stroke patients get insufficient care, and the same is true for 45 percent of asthma patients and 60 percent of pneumonia patients. Knowing the right steps and trying hard aren’t enough.

A Different Strategy

Those on the receiving end of such failures naturally react with outrage. We can forgive ignorance and accept that others tried their best with what they knew. But when the experts know what to do and fail to do it, we’re likely to blame gross negligence, incompetence, or heartlessness. This ignores the complexity of many jobs today.

Why do I make so many mistakes, and how can I avoid them?

The problem is that across numerous professions — medicine, engineering, finance, business, government — the level and complexity of our knowledge is more than any individual can apply correctly in all circumstances. Knowledge has saved and also overwhelmed us.

Most professions, especially medicine, have traditionally responded to failure by requiring more training and experience. Training of medical personnel, police, engineers, and others is more extensive than ever. Due to increased training requirements, doctors don’t practice independently until their mid-thirties. But while training and experience are important, expertise doesn’t address human fallibility. We need a different strategy for preventing failure that takes advantage of knowledge and experience but also compensates for human flaws.

The solution is a simple checklist.

How to Create a Checklist

(Shortform note: also see the “A Checklist for Checklists.”)

This is how you can stop asking yourself, Why do I make so many mistakes?

Before creating a checklist, decide two things:

1) Define a clear ‘“pause point” at which the checklist is to be used (unless the moment is obvious, such as when something malfunctions).

2) Decide whether to create a Do-Confirm list or a Read-Do list.

To use a Do-Confirm checklist, team members perform their jobs from memory. Then they stop and go through the checklist and confirm that they completed every item on the checklist. In contrast, to use a Read-Do checklist, people carry out each task as they check it off, like a recipe.

(Shortform note: Choose the type of checklist that makes the most sense for the situation. For instance, a Read-Do list could be used when the sequence needs to be exact or the entire effort will fail, like in operating machinery or listing emergency tasks. A Do-Confirm list gives more freedom and is allowable when the stakes are lower, and a forgotten step can be done later out of sequence.)

Once you’ve chosen which type of checklist you’re creating, follow these guidelines (and stop asking yourself, Why do I make so many mistakes?):

- Keep the checklist short, typically five to nine items, which is the limit of short-term memory. After 60 to 90 seconds, a checklist becomes a distraction from other things. People are likely to skip or miss steps.

- Focus on the “killer” items or steps that are most dangerous to miss but that are still sometimes overlooked.

- Remember that checklists are not supposed to be how-to guides. They are quick, simple tools to aid the recall of experts.

- Keep wording simple and exact.

- Use language and terminology familiar to the user.

- Fit the checklist on one page.

- Avoid clutter and unnecessary or distracting colors.

- Use upper and lowercase text in a sans serif font for ease of reading.

Test your checklist in the real world — have people use it and provide feedback. Boorman tests his checklists in a flight simulator. Language that you think is clear may not be to someone else. In practice, things are always more complicated than anticipated. Keep revisiting and testing the checklist until it works consistently.

Why do I make so many mistakes? You won’t if you follow a checklist.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best summary of "The Checklist Manifesto" at Shortform . Learn the book's critical concepts in 20 minutes or less .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Checklist Manifesto summary :

- How checklists save millions of lives in healthcare and flights

- The two types of checklists that matter

- How to create your own revolutionary checklist