This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Skin in the Game" by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What does “virtue signaling” mean? Do you think it’s immoral to publicize your virtue?

The term “virtue signaling” has slowly been creeping its way into everyday vernacular and media dialogue. Virtue signaling is the act of publicly behaving in a way that makes you look as noble as possible.

Here is why true virtue is done in secret.

What Is Virtue Signaling?

The criticism of virtue signaling has exploded in popularity in recent years, especially online. But what does “virtue signaling” mean and why the criticism?

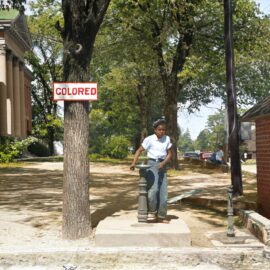

As the name suggests, virtue signaling refers to behaving or speaking in ways that “signal your virtue” to others. No one would deny that it’s immoral to pretend to help others for your own gain, but some argue that accusations of virtue-signaling have become increasingly unfounded.

More frequently, anyone who does anything virtuous is accused of virtue-signaling. While, ideally, all virtue is done in secret, honest virtue isn’t invalidated just because someone was there to see it. And ironically, many of those who accuse others of virtue-signaling are doing so to bolster their own reputations and claim moral superiority themselves.

Practice Virtue in Secret

Never advertise your own virtuous actions or beliefs—practice virtue in secret. The only way you can be sure that you’re doing good is if you’re receiving nothing in return. Otherwise, you risk taking advantage of those you’re claiming to help.

The highest possible virtue is doing good even when it means you’ll be punished for it. The only virtuous opinions you should broadcast are the ones that oppose the dominant consensus, when you risk harming your reputation, or worse, for standing up for what’s right. Think of Malala, the Pakistani activist who was shot in the head by a Taliban assassin for her advocacy for women’s education.

Virtue Signals Are Empty Words

People often signal their virtue by being vocal about their support of “virtuous” ideologies but are unwilling to make the sacrifices that the ideology logically requires.

To illustrate, Taleb describes the time he met writer and activist Susan Sontag. He recounts how she behaved rudely toward him after learning he used to be a trader, pointedly denouncing the market system.

Taleb asserts that it was immoral for Sontag to live in active opposition to the free market while reaping its benefits—he reports that Sontag fiercely negotiated for large sums of money from publishers and lived in a New York City mansion sold for $28 million. This is a skin in the game imbalance—by advocating for a lifestyle without living it, she was detaching her rewards from the influence she had on others.

If Sontag wanted to pursue her activism morally, she should have put skin in the game by living the lifestyle she advocated for, in a collectivist commune isolated from the free market she fought against. In contrast, Taleb praises progressives Ralph Nader and Simone Weil for living austere lives in accordance with their principles.

| Sacrifices Made on Principle Taleb doesn’t go into too much detail about how Nader and Weil live according to their virtues—let’s take a closer look here.Ralph Nader is an activist famous for sparking reform in a wide range of industries with the goal of protecting consumers from the abuse of power by corporations and government. In alignment with his environmentalist ethic, he doesn’t own a car and relies on the bare minimum of electricity, preferring to write on a typewriter. Taleb says he “leads the life of a monk”—and he does. Nader has never married, and lives in a tiny apartment off of $25,000 a year. Simone Weil was a French philosopher and political activist motivated by a need to improve the conditions of the working class. In order to truly understand the impact she wanted to have, Weil quit her job as a high school teacher to spend a year doing grueling work in car factories. She eventually put her life on the line, traveling to Spain to enlist in another country’s civil war, against the authoritarian Nationalist faction. She died of tuberculosis at the age of 34, refusing to eat any more than those in her home country of France were able to under Nazi control. Though some of this self-denial may seem unnecessary, Nader’s and Weil’s sacrifices served the very real purpose of putting skin in the game. Those who promote change at a massive scale require greater accountability because the potential harm they could do is greater. |

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Nassim Nicholas Taleb's "Skin in the Game" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Skin in the Game summary :

- Why having a vested interest is the single most important contributor to human progress

- How some institutions and industries were completely ruined by not being invested

- Why it's unethical for you to not have skin in the game