This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Color of Law" by Richard Rothstein. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What was redlining under the New Deal? How did the New Deal’s redlining policies segregate American communities?

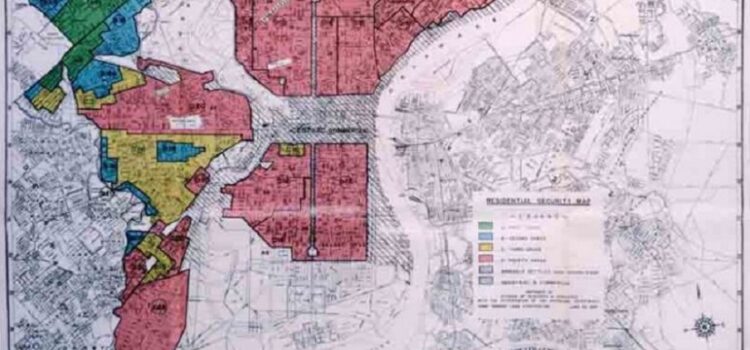

In the New Deal, redlining was based on a color-coded map for evaluating the value of homes in each neighborhood. The redlining practice contributed to segregation because the vast majority of neighborhoods colored red were African American neighborhoods.

Read on to learn more about how the New Deal’s redlining practices entrenched segregation in America.

The Genesis of the Home Owners Loan Corporation

Hoover’s efforts to promote homeownership were ultimately no match for the Depression, and when Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office, homeownership remained out of reach for most working- and middle-class families; even families who already owned their homes were having trouble making their mortgage payments.

Roosevelt responded to these challenges by creating two agencies, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). As a rule, both agencies systematically discriminated against Black Americans. This practice that resulted from the new Deal is known as redlining.

How the Home Owners Loan Corporation Created the Discriminatory New Deal Redlining Practices

Designed to keep current homeowners in their homes, the HOLC bought mortgages in danger of default and reissued them to the holder with more generous terms. For example, in the ’30s, most mortgages required 50% down payments, and borrowers could only pay off interest, not principle, until the mortgage came due after 5–7 years. The HOLC, however, offered borrowers 15-year terms and amortized payment plans (amortized payments include part of the principle as well as interest). This meant owners could gain equity in their homes even as they paid off their loans.

Although the HOLC’s mission was altruistic, it still expected its beneficiaries to make the payments to which they were obligated. So, to assess the risk of particular borrowers, the agency hired local real estate agents to appraise properties and neighborhoods. These real estate agents, bound by a segregationist code of ethics that assumed African American residents equaled lower property values and so higher risk of default, produced color-coded maps of metropolitan areas for the government to use as a guide for evaluating homes. The agents used red for neighborhoods with any African American residents—no matter how well off—and green for all-white neighborhoods, a practice that would come to be known as “redlining.” Residents in green neighborhoods had an easier time securing loans and thus were able to cement the monoracial—that is, white—makeup of those neighborhoods.

One representative example of redlining under the New Deal took place in St. Louis. In 1940, an appraiser colored Ladue, a suburb of the city, green, because no foreigners or African Americans lived there. Lincoln Terrace, a suburb with comparable housing stock and equally middle-class residents, was colored red—because it was predominantly African American.

How the Federal Housing Administration Exacerbated the Destructive Effects of Redlining

Although the HOLC did occasionally assist homeowners in redlined tracts, the redlined maps set a standard in the government—that certain neighborhoods were undesirable or problematic simply because they contained African Americans.

This standard was especially destructive when it came to the Federal Housing Administration (or “FHA”), whose mission was to increase homeownership by insuring new bank mortgages and facilitating more favorable terms (20% down; 20-year, amortized payment periods).

Like the HOLC, the FHA performed appraisals on the properties whose mortgages a bank wanted to insure. In 1935, the FHA issued its first manual to its appraisers; the manual explicitly referred to integration as leading to “instability” and a “reduction in values.” It also said that properties in neighborhoods that excluded “inharmonious” racial and ethnic groups should receive high ratings, thus increasing the likelihood homes in that neighborhood would be insured. The manual favored suburbs over urban areas, and it singled out integrated schools as a sign of lending risk. Subsequent editions of the manual, right up until 1952—i.e., throughout and after World War II—maintained similar guidelines.The effects of this racialized policy were significant. For one, it prevented Black families from moving to the suburbs, where many white families were relocating. For example, in 1941, a real estate agent in New Jersey tried to sell twelve homes in a development called Fanwood to African American families. All the families had good credit, and local banks were willing to finance their purchase if the FHA would insure the mortgages. But the FHA declined, writing that no loans would be given to “colored developments.” Today, Fanwood’s African American population is about 5% while the county in which it’s located is 25% Black.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Richard Rothstein's "The Color of Law" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Color of Law summary :

- How racial residential segregation is the result of explicit government policy

- The three reasons why racial segregation is so difficult to reverse

- The steps that could lead to a more integrated and equitable society