This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "First, Break All the Rules" by Gallup Press. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What criteria do you base your hiring decisions on? Do you—like most organizations—hire candidates based on skill and relevant work experience? What other variables do you factor in?

Historically, organizations have hired based on three criteria: experience, intelligence, and determination. However, these things don’t necessarily translate into excellent performance. According to Marcus Buckingham, the author of First, Break All the Rules, the key to effective hiring is to hire for talent, not experience or intelligence.

Here is why you should, first and foremost, hire fore talent, not experience or other factors.

Why You Should Hire for Talent

Most businesses hire based on experience, intelligence, and determination rather than hiring for talent. This is because:

- An experienced candidate has spent time in the workforce and learned lessons along the way. When compared to someone with no experience, this candidate has likely already dealt with obstacles and figured out how to navigate them.

- An intelligent candidate has the ability to adapt to different positions. Because they possess the brainpower, they’re able to figure out how the position works and how to most effectively handle the task.

- A determined candidate has the drive to work effectively. Even if they don’t possess the talents necessary for the position, they possess a passion that can’t be taught. Their determination creates a willingness to learn and adapt.

However, when you look at a pool of employees that were hired using these criteria, there is often a high range in the quality of their work. Some employees work efficiently and without issue. Others work slowly and cause problems.

If they all meet the standards of these criteria, what is the reason behind these discrepancies? The answer is differing talents. If a candidate has the experience, intelligence, and determination, but lacks the talents necessary to effectively perform in a specific role, they won’t excel in the position. The solution? Hire for talent.

The Manager’s Purpose

The purpose of a manager is to help employees translate the talents they already have into performance. In contrast, trying to teach someone a talent that they simply don’t possess is time-consuming and ineffective. Instead of focusing on the things that an employee lacks, focus on what they bring to the table.

If you disregard talents when hiring, you risk putting someone into a position that they aren’t equipped to handle, even if they have skills and knowledge that suggest otherwise. For example, if you hire a customer service representative who lacks the thinking talent of problem-solving, they may struggle when a customer approaches them with an issue that was not described during the onboarding process. Though they have the knowledge to address standard issues, they lack the talents necessary to apply them to a unique situation.

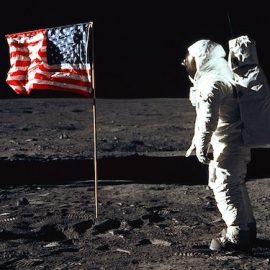

The Range of Performance in NASA’s Astronauts

In the 60s, Brigadier General Don Flickinger was tasked with assembling a team of astronauts to lead the United States’ foray into space. When looking for candidates, Flickinger assessed a variety of criteria including age, height, experience, intelligence, and athletic ability. He then ran candidates through intense psychological and physical tests. Ultimately, he chose seven men.

Despite similarities in experience and intelligence, the performances of these seven astronauts varied drastically. On the one hand, astronauts such as John Glenn and Gordon Cooper ran successful missions and became public figures. On the other hand, astronauts such as Gus Grissom and Scott Carpenter made critical errors that led to the loss of millions of dollars worth of property.

What led to this significant range of performance? Natural talent. For example, during takeoff, Glenn’s pulse never rose above 80. Grissom’s spiked to 150. This is because Glenn had a talent for keeping calm under pressure where Grissom didn’t. It shouldn’t come as a surprise, then, that Grissom’s critical error occurred after he had a panic attack and blew his capsule’s hatch too early after splashing down on Earth. This caused NASA’s expensive vessel to sink to the bottom of the ocean, never to be recovered.

Unclear Language

You now know the difference between skills, knowledge, and talent. With this in mind, look more closely at the language you use to describe the ideal worker. To strengthen your ability to communicate expectations and encourage growth, you need to clarify when you’re referring to skills and knowledge that your employees can develop versus talents that they have little control over.

Term #1: Competencies

Many companies use the term “competencies” to define behaviors that they expect from their employees. The problem with the term is that “competencies” can describe skills, knowledge, or talents.

For example, many companies consider the ability to follow standards as a competency for managers. This is a skill that relies on the manager’s knowledge of the company’s policies and, therefore, can be learned and developed. However, many companies also consider the ability to keep calm under pressure as a competency. This is a talent and, therefore, can’t be learned or developed.

Term #2: Habits

The term “habit” refers to anything that is second nature. You’ve been told that you can change any habit with enough willpower and effort. However, most habits are talents, and, therefore, can’t be changed.

For example, if you’re habitually aggressive, you likely won’t be able to stop the feelings of aggression that emerge whenever you feel attacked or cornered. However, you can develop habits based on skills that allow you to handle your aggression such as counting to ten or stepping away from a situation before speaking.

Term #3: Attitude

Many companies press their managers to create an environment where everyone has a positive attitude. However, a manager has little control over their employee’s attitudes because a person’s primary attitude is based on the way that their brain filters information according to their talents.

For example, if someone has a talent for empathy, their brain likely filters cynicism or denial out when they listen to other people describe their problems. What’s left is a willingness to listen and embrace the emotions of others. These behaviors and feelings become their attitude.

Term #4: Drive

Managers often treat drive as something that can be created through education or willpower. However, drive specifically relates to striving talents (talents that inform your motivations) and can’t be changed.

For example, if you have an employee that lacks the striving talent of competitiveness, you’re not going to motivate them using an in-house contest. Their behavior won’t change because their actions aren’t motivated by competition.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Gallup Press's "First, Break All the Rules" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full First, Break All the Rules summary :

- Why only 13% of the world’s workforce is actively engaged at work

- How to find strong employees and keep them

- The 12 questions to ask your employees that help you determine the strength of your organization