This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Antifragile" by Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

Are you looking for Antifragile quotes? How can these quotes help you understand antifragility, and encourage you to build antifragility yourself?

Antifragility is all about the idea of growth through struggle. As we go through life, we continuously grow and learn, and can apply our past struggles to our future success. These Antifragile quotes help explain how that works.

Keep reading for six motivational Antifragile quotes.

Antifragile Quotes and Explanations

These Antifragile quotes cover key ideas in the book like medical convexity, antifragile education, and growth through struggle. Check them out to understand the book and its most exciting ideas.

“The psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer has a simple heuristic. Never ask the doctor what you should do. Ask him what he would do if he were in your place. You would be surprised at the difference”

This is called the agency problem: The one making decisions (the agent) is doing so for his or her own benefit rather than the benefit of the clients. While iatrogenics originated in medicine, it and the agency problem occur in numerous fields. No matter the field, though, it starts with modern, “rational” people thinking that their intervention will make things better.

Statisticians have estimated that reducing medical expenditures (only up to a point and only on elective treatments) would actually increase the average lifespan in wealthy countries like the U.S. by reducing iatrogenics. This is one large-scale application of the “less is more” principle.

This isn’t an argument that medical care should never be given, just that we should be much more discerning about when and how much we intervene. The iatrogenics of any given drug or treatment are linear—they increase or decrease consistently with how much of the treatment is given. However, the benefits of that treatment can be convex (having accelerating benefits) based on how severe the patient’s condition is.

“Few understand that procrastination is our natural defense, letting things take care of themselves and exercise their antifragility; it results from some ecological or naturalistic wisdom, and is not always bad — at an existential level, it is my body rebelling against its entrapment. It is my soul fighting the Procrustean bed of modernity.”

Given modern humans’ tendency to intervene in everything, we view hesitating to intervene—that is, procrastinating—as some kind of defect or sickness. The supposed “cures” range from changing your environment, to pursuing a new career, to simply powering through it. The problem is compounded by the fact that inaction is hardly ever rewarded; you get a bonus for the problem you solve, not the one that never happens in the first place.

However, in many cases, procrastination is your body trying to tell you something important. For example, an author who procrastinates on writing a book may be doing so because it’s not what he or she should be writing about, either because of lack of expertise or lack of interest. For a more dramatic example, the Roman general Fabius Maximus irritated the conqueror Hannibal to no end by repeatedly delaying and avoiding military engagements that he was sure to lose. In Maximus’s situation, procrastination was the best strategy and indeed the only viable one.

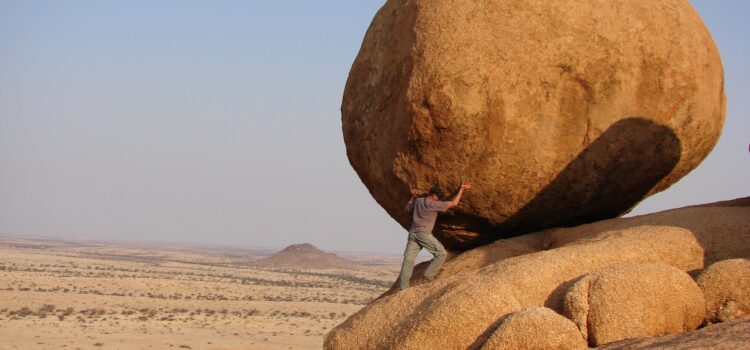

“Difficulty is what wakes up the genius”

Doctors have observed extreme cases of antifragility in humans, which they call post-traumatic growth. In simple terms, it’s the opposite of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). While those who experience the much more well-known PTSD continue to suffer from past events, those who experience post-traumatic growth are somehow improved by it. In fact, there’s a short test that suggests various forms that improvement could take: the Post Traumatic Growth Inventory.

However, while many people may not have heard of post-traumatic growth, almost everyone has heard some variation of the expression “what doesn’t kill me makes me stronger.” Perhaps this is just another example of domain dependence at work.

Another phrase, “necessity is the mother of invention,” points to another, more immediate, sort of antifragility seen in humans. Basically, what happens is that people overreact to setbacks—they’re spurred to use more energy and effort than is needed to compensate for the problems. That excess energy goes on to become innovation and progress.

“If there is something in nature you don’t understand, odds are it makes sense in a deeper way that is beyond your understanding. So there is a logic to natural things that is much superior to our own. Just as there is a dichotomy in law: ‘innocent until proven guilty’ as opposed to ‘guilty until proven innocent’, let me express my rule as follows: what Mother Nature does is rigorous until proven otherwise; what humans and science do is flawed until proven otherwise.”

Scientific theories are a key underpinning of rationalization and a dangerous one. Scientists frequently promote theories without stopping to consider the damage that might happen if those theories are wrong.

Science—that is, rigorous testing and observation—can be done without resorting to theories at all. There’s even a name for it: phenomenology, the study of phenomena that currently have no theories explaining them. While theories are fragile and often vanish as quickly as they appear, phenomena are durable; they happen the same way every time.

Social sciences are especially vulnerable to flawed theories, and even the theories themselves seem to vary wildly from one school of thought to another. In the cold war years, the University of Chicago was pushing laissez faire economics while the University of Moscow taught the complete opposite. Even calling such ideas “theories” stretches the definition a bit because theories are supposed to be closely examined and supported with concrete evidence.

“The irony of the process of thought control: the more energy you put into trying to control your ideas and what you think about, the more your ideas end up controlling you.

Forecasting or predicting the future is notoriously hard to do. Consider the infamous inaccuracy of weather forecasts, and then realize that those are based on much more concrete information than, for example, a large company’s financial projections for the coming year.

So much of our modern obsession with control is based on forecasting—predicting upcoming events so that we can be ready for them or, better still, prevent them. However, actions taken based on these inaccurate forecasts are often more harmful than helpful. If you’ve ever trusted a forecast that says the day will be clear and sunny, then gotten rained on because you didn’t bring an umbrella, you understand how that can happen.

“Antifragility is beyond resilience or robustness. The resilient resists shocks and stays the same; the antifragile gets better.

We live in an unpredictable world. The models and theories we use to try to predict the future invariably fall apart as unforeseen events prove them wrong and, in turn, destroy the plans we made based on those models. Clearly, systems based on such flawed models are bound to be fragile—easily broken.

The solution to this problem is antifragility. Instead of a never-ending search for more accurate models and better predictions, all we need to do is make sure that we’re in a position to benefit from uncertainty and volatility instead of being harmed by it.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Nassim Nicholas Taleb's "Antifragile" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full Antifragile summary :

- How to be helped by unforeseen events rather than harmed by them

- Why you shouldn't get too comfortable or you'll miss out on the chance to become stronger

- Why you should keep as many options available to you as possible