This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "The Mother Tongue" by Bill Bryson. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here .

What is Early Modern English? What are the major linguistic developments that took place during this period?

The Early Modern English period extends roughly from 1500 to 1800 CE. The major developments during this period were the Great Vowel Shift, the invention of the printing press, and the English spelling reform. It was also the time of William Shakespeare, who made a remarkable contribution to the standardization and exaltation of the English language.

Read about the key events and linguistic developments that took place during Early Modern English.

The Arrival of Early Modern English

The Early Modern English phase extends from the late 15th century to the mid-to-late 17th century. The transition from Middle English to Early Modern English was not just a matter of the addition of new words and minor changes to pronunciation. It was the beginning of a whole new era in the history of the English language. It is during this period that English developed many of its modern features.

The Great Vowel Shift

Perhaps, the major factor that separates Middle English from Early Modern English is the culmination of the revolution of the phonology of English (the Great Vowel Shift), running roughly from 1400-1600 CE, during which English speakers began pushing vowels closer to the front of their mouths. The word life, for example, was pronounced lafe in Shakespeare’s time, with the vowel lodged further back in the throat.

The Printing Press

Another key event of the Early Modern English period was the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, which resulted in the gradual spread of written works (and thus, literacy) throughout England. By 1640, there were over 20,000 titles available in English, more than there had ever been.

And as printed works produced by London printers began to spread across the country, local London spelling conventions gradually began to supplant local variations. As with the Great Vowel Shift, the sheer weight of London’s gravity was decisive. By the dawn of the 18th century, English had become far more unified in its spelling than it had just a generation before.

What this also meant was that old spellings became fixed just as many word pronunciations were shifting. Consequently, our inheritance is a written language with many words spelled the way they were pronounced 400 years ago. Such spellings often bear little resemblance to how the words are actually spoken. This accounts for many of the silent letters in words like knight and aisle, which used to be pronounced more phonetically than they are today.

Spelling Standardization

This incongruity of spelling and pronunciation led some notable public figures to champion more robust efforts at spelling standardization and simplification by the end of the 18th century. By the late 19th century, spelling reform groups like the American Philological Association even began to lobby for new spellings like tho, wisht, and hav in an effort to simplify American English spelling and have it more closely align with pronunciation

Despite the great passion and energy poured into spelling reform efforts, however, they mostly failed in their mission. Language is such a fluid and organic tool, used differently by so many people and susceptible to innumerable internal and external influences, that it is quite impossible for some centrally directed body to impose reforms top-down.

Today, we are used to the non-phonetic spellings of words like bread. It would be deeply strange and unnatural for us to write bred. And of course, bred is itself a word, which would merely create confusion. Bread and bred are homophones, words that sound the same but are spelled differently. The high number of homophones in English gives the non-phonetic spellings of many words a useful purpose. Thus can we distinguish might from mite, great from grate, and sure from shore. Perhaps our spelling isn’t so irrational after all.

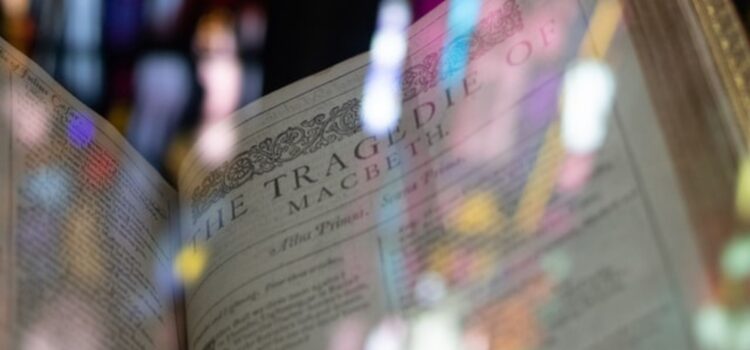

At this time, English began to be regarded for its potential as a language of literature. No writer took greater advantage of the incredible flexibility and richness of the English language than Shakespeare. The Bard of Avon alone added some 2,000 words to the language, such as mimic, bedroom, lackluster, hobnob. He also introduced a host of new phrases we still use today, like “one fell swoop” and “in my mind’s eye.” Shakespeare greatly elevated and exalted the English language.

For much of the history of the evolution of the English language, however, words defied standard spelling, with even Shakespeare offering a bewildering array of different and inconsistent spellings for the same words throughout his works. The first steps toward standardization only began with the invention of the printing press in the 15th century and the gradual spread of written works (and thus, literacy) throughout England.

By 1640, there were over 20,000 titles available in English, more than there had ever been. As printed works produced by London printers began to spread across the country, local London spelling conventions gradually began to supplant local variations. What this also meant was that old spellings became fixed just as many word pronunciations were shifting because of the Great Vowel Shift. Our inheritance is a written language with many words spelled the way they were pronounced 400 years ago. As a result, English spellings often bedevil non-native speakers, as well as those who’ve spoken the language their whole lives. Pronunciation and spelling are frequently divergent. To take just one example, the sh sound can be spelled sh as in mash; ti as in ration; or ss as in session. The troublesome orthography (the set of conventions for writing) of English can be seen in words like debt, know, knead, and colonel, with their silent letters, as well as their hidden, but pronounced letters.

Shakespearean Influence

Early Modern English also saw a Golden Age of English literature, championed by William Shakespeare. No writer took greater advantage of the incredible flexibility and richness of the English language than Shakespeare. In the late-16th and early-17th centuries, the Bard of Avon alone added some 2,000 words to the language, like mimic, bedroom, lackluster, hobnob. He also introduced a whole host of new phrases that we still use today, like “one fell swoop” and “in my mind’s eye” owe their origins to Shakespeare. He reshaped English, showcasing its extraordinary possibilities as a language of literature.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Bill Bryson's "The Mother Tongue" at Shortform .

Here's what you'll find in our full The Mother Tongue summary :

- How English became a global language

- How the invention of the printing press led to standardization of written English

- Why English dictionaries are the most comprehensive found in any language