What led to the dramatic transformation of the Ottoman Empire after WWI? How did European powers reshape the territories they gained from the fallen empire?

The collapse of one of history’s longest-lasting empires led to significant changes across the Middle East and Central Asia. Historian David Fromkin explains that, through the 1922 settlement, European powers divided territories, created new countries, and established spheres of influence that would impact the region for generations to come.

Keep reading to discover how these decisions shaped several Middle Eastern countries and continue to influence regional politics today.

The Ottoman Empire after WWI

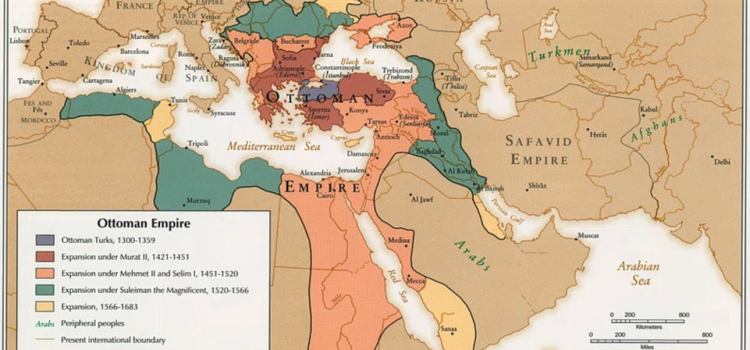

In A Peace to End All Peace, David Fromkin discusses what happened to the Ottoman Empire after WWI. European powers drew up what he calls the 1922 settlement—a long list of agreements European powers and Middle Eastern leaders arrived at around 1922. The agreements determined which Ottoman Empire territories would become independent countries and which would be absorbed by European empires such as Britain, France, and Russia. The agreements impacted the countries throughout the region, from Egypt—which gained independence—to Afghanistan. We’ll focus on some of the most controversial decisions.

(Shortform note: 1922 was a year of many significant global changes in addition to this settlement. Britain signed a treaty granting Ireland independence. In India, Gandhi was sentenced to six years for protesting British rule, foreshadowing India’s fight for independence. Meanwhile, fascist dictator Benito Mussolini rose to power in Italy.)

Regarding Russia, the settlement defined its political borders along the Türkiye-Iran-Afghanistan line. Fromkin writes that the Russian proclamation of a Soviet Union in 1922 consolidated its control over Muslim Central Asia, quashing independent movements and integrating the territory into the new Soviet state.

(Shortform note: In addition to quashing independence movements, the Soviet Union attempted to stifle Islam throughout Central Asia. The USSR’s state religion was atheism, so it banned Islam to force acculturation into the dominant Soviet Russian culture, which some argue led to many believers becoming radicalized.)

Key Outcome: The 1922 Settlement Unsettles the Middle East

Fromkin describes how Europe reshaped the Middle East post-World War I. Some countries became independent, but Fromkin explains that independence came at a cost, whether it was war or foreign intervention. Greater Syria fell under France and Britain’s direct control, and the European administration of the region led to the creation of several new countries.

(Shortform note: The League of Nations was a precursor to the United Nations, established with the hopes of preventing another global conflagration. After World War I, some of the territories that had been part of the losing empires were placed under the Mandate of one of the Allies. In addition to the British and French Mandates in the Middle East, several countries in Africa and the Pacific were placed under this model of governance.)

We’ll discuss how the 1922 settlement shaped nine Middle Eastern countries and contributed to their instability.

Türkiye

According to Fromkin, the harsh terms Europe imposed on Türkiye as part of the postwar agreements led to the Turkish War of Independence.

Through the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, Europe dismantled the Ottoman Empire and imposed large territorial losses and heavy financial reparations on Türkiye, the empire’s seat of government. The Treaty fueled nationalist sentiment and ignited the Turkish War of Independence, which killed hundreds of thousands of Turkish, Greek, and Armenian civilians. Turkish forces succeeded, leading to the establishment of the Republic of Türkiye and the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923, which recognized the borders of the modern Turkish state.

(Shortform note: Before nationalism took hold, Turkish society debated different alternatives for their future. A Western takeover seemed imminent, and the question was which power was preferable. One faction advocated for an American mandate because President Wilson gave signs of recognizing Turkish sovereignty. Another faction preferred a British mandate since their centuries-long friendship with Britain had only been broken by the Young Turks, who were no longer in power. A third faction argued against a mandate altogether, proposing Türkiye establish a relationship with the US to receive aid to rebuild without relinquishing its autonomy. Eventually, as we note above, nationalist forces won the debate.)

Iraq

The decision to create Iraq by uniting the ethnically and religiously diverse regions of Mesopotamia led to persistent infighting and questioning of the country’s legitimacy. According to Fromkin, the country still grapples with internal conflicts as a result of the rivalries between the Shia and Sunni strands of Islam and with minority ethnic groups such as the Kurds.

(Shortform note: The division between Shia and Sunni Muslims goes back thousands of years. Following Prophet Muhammad’s death in 632, a dispute arose over his successor. Shiites wanted the next leader to be from within Muhammad’s family, whereas Sunnis preferred selecting the most capable leader from the community.)

Fromkin explains how, after World War I, Mesopotamia became more strategic thanks to its oil reserves. At the same time, it was becoming more difficult for the British to govern it. The population often rose up against the British occupation, resulting in violent confrontations. In 1921, the British government handpicked the first Iraqi king so they could stop governing the region directly while still protecting their commercial interests. However, they chose a Sunni king, which made the Sunni minority into a ruling elite over the Shiite majority population.

(Shortform note: Some argue that US interventions in Iraq mirrored Britain’s actions. After “liberating” Mesopotamia from the Ottomans, Britain’s imposed proxy government in Mesopotamia lacked legitimacy, requiring frequent intervention. Decades later, the US dismantled local rule to “free” Iraq from Saddam Hussein’s dictatorship, exacerbating sectarian divides. Critics suggest British and American interventions led to violence and weakened national unity, contradicting their alleged goals of liberation and nation-building.)

During the postwar decision-making period, Europe decided not to facilitate a Kurdish kingdom. Fromkin writes that the discussions on the subject didn’t materialize into any decision, which effectively left the Kurds without a state of their own. (Shortform note: The Kurds are an ethnic group comprising several languages and religions. Today, the Kurdistan Region is an autonomous territory within Iraq, but Kurds live throughout Iraq, Turkey, Syria, and Iran.)

Saudi Arabia and Transjordan (Jordan)

Britain shaped today’s Arabian Peninsula in two ways. They made the Palestinian region of Transjordan into a separate state, and they backed a leader of Transjordan in opposition to the rising leadership of Ibn Saud in today’s Saudi Arabia. We’ll discuss both actions in more detail.

Fromkin explains that Britain’s administrative actions in Transjordan eventually led to the creation of Jordan. To control anti-French and anti-Zionist movements without overextending resources, Britain elevated Abdullah I bin Al-Hussein of the Hashemite royal family to lead Transjordan. This move contradicted Britain’s policy against Jewish settlement near territories led by Arabian leaders, so they separated Transjordan from Palestine to bypass this policy.

Fromkin argues that Britain’s support for Abdullah divided the desert Arabs and created lasting questions about Jordan’s legitimacy. Britain backed Abdullah in the west but tacitly approved Arab political leader Ibn Saud in the east. Ibn Saud embraced Wahhabism, a conservative Islamic movement, to expand his territory, threatening Abdullah’s control.

(Shortform note: Wahhabism is a movement within Sunni Islam that advocates for a conservative practice of Islam. For example, it follows the Koran strictly and forbids smoking and alcohol. Advocates of Wahhabism refer to themselves as Salafis, and they view the term Wahhabi as derogatory since it was coined by its opponents.)

With British military backing, Abdullah retained some land, but Ibn Saud expanded across Arabia without confronting Britain directly. This rivalry led to the modern borders between Saudi Arabia and Jordan. According to Fromkin, it also encouraged Jordan’s critics to question its legitimacy, since it arguably could not have survived without Britain’s support.

(Shortform note: While Fromkin views Jordan as a British creation, others argue that British and Arab interests, especially the Hashemites, were equally influential in creating it. In addition, they claim that if Britain had allowed the Arab population to decide for themselves how to organize politically after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the region would’ve been engulfed in violent fighting between different royal families and sectarian interests. They cite evidence that tribal rivalries like the Sauds and Hashemites existed before British involvement. In addition, while Fromkin argues that Jordan’s reliance on British support contributed to the questioning of its legitimacy, others argue that Jordan’s support for Israel is at the root of the illegitimacy claims.)

Syria and Great Lebanon (Lebanon)

According to Fromkin, France’s decision to divide Syria-Lebanon into autonomous regions led to conflicts and bloodshed. Arab nationalists opposed French rule and declared Syria-Lebanon independent in 1920. But France was determined not to lose Syria-Lebanon, which was theirs according to Sykes-Picot, and they invaded Damascus.

Between 1920 and 1923, France consolidated its control over the region through military conquest and administrative division. In 1923, the League of Nations confirmed the French Mandate over Syria-Lebanon. During their administration of the region, the French implemented a policy of divide and rule to weaken nationalist movements by worsening sectarian and regional differences. They broke up the region into different administrative areas, making it difficult for the different groups resisting them to collaborate and successfully reject the French.

(Shortform note: Historians explain that the leaders of Syria-Lebanon planned to take a cue from the US by governing as a federation rather than using France’s policy of divide and rule. Their proclamation of independence had the support of Muslim, Jewish, Christian, and Greek Orthodox communities. In addition, they planned for Greater Syria to be an independent state in federation with the Kingdoms of Arabia and Iraq. In defending their plan, Syrian leaders argued that it was crucial for major powers to recognize smaller nations’ right to self-determination to avoid more conflict and war. Regardless of their proclamation, France invaded Syria and the coalition disintegrated, leading to continuing divisions between liberal and Islamist Syrians.)

France divided Syria-Lebanon into several autonomous regions, including Great Lebanon—a precursor to modern-day Lebanon. Fromkin claims that redrawing Lebanon’s borders led to bloodshed in the 1970s and 1980s due to conflicts between the majority Muslim population and the minority Christian groups which were brought together artificially.

(Shortform note: Fromkin is referring to Lebanon’s 15-Year War, which includes the Lebanese Civil War, Syrian interventions, the Israeli invasion and Lebanese resistance, the War of the Camps, and the Presidential Crisis. Analysts argue that in addition to differences between religious communities, intersecting factors such as economic inequality and international pressures also contributed to the conflict. For example, although Lebanese Christian and Muslim communities both had gaping economic inequality, Christians were more likely to be wealthy and Muslims were more likely to be working class. Christians were also more likely to hold political power as a result of the policies the French instituted during their mandate.)

Palestine and Israel

In Palestine and Israel, the British government’s decision not to follow through on their promises to either Arabs or Zionists led to a still-unresolved dispute. The British administration committed itself to creating a Jewish home in Palestine without specifying what that meant. Fromkin argues that many British leaders believed it meant an expanded Jewish community within a multinational Palestine under British rule, not a Jewish state. However, the British had given the impression to their Zionist allies that they’d establish a full-blown Jewish state.

Fromkin explains that Zionist leaders felt constrained by the British administration’s wavering stance. They believed that if the British made it clear that the Balfour Declaration was non-negotiable and would be enforced, Arabs would be forced to accept it and even see its potential benefits, like increased economic development in the region.

According to Fromkin, the main obstacle to negotiations among the British, the Jewish settlers, and the Palestinians was the Palestinian delegation’s uncompromising stance. They were worried about losing their land. Some Palestinian groups responded to the increasing Jewish immigration with violence. Deadly anti-Zionist riots broke out against incoming Jewish settlers, leading Britain to suspend Jewish immigration into Palestine temporarily. In addition, Fromkin writes that the British officers in Palestine—not politicians but rank-and-file members of the army—sided with the Palestinians, doing little to suppress the violence. When the British army didn’t react quickly enough to restore order, Jewish militias took up arms to protect themselves.

Finally, Fromkin highlights Britain’s White Paper for Palestine, which Churchill wrote to bring order to the region. The document reiterated support for a Jewish national home in Palestine without making it into a Jewish state. It left Palestinian and Zionist leaders dissatisfied: Zionists wanted more support for their project, while Palestinians wanted to end the project entirely.

| Tragedies of British Rule in Palestine Churchill’s 1922 document was the first of three White Papers on Palestine, continuing Britain’s wavering stance on whether Palestine should be a multinational territory under British rule, a Jewish state, or an Arab state. Like earlier British policies, these papers heightened tensions and affected both Jews and Palestinians for generations. In addition to causing the conflicts Fromkin describes, the 1922 White Paper affirmed the Balfour Declaration and Jewish rights in Palestine but restricted Jewish immigration and excluded Transjordan from Jewish settlement. To this day, some elements of Israel’s political leadership argue that Jordan should be part of Israel. The 1930 White Paper followed the 1929 Arab riots. The riots erupted after a group of Jewish settlers raised the Zionist flag in the Western Wall (a sacred site for both Muslims and Jews in Jerusalem). However, the discontent of the local Arab population ran deeper, including fears about losing political and economic independence. In response to the hostilities, the 1930 White Paper further restricted Jewish settlement, though these restrictions were later eased following complaints from Zionist leaders. Finally, the 1939 White Paper had tragic consequences. It outlined plans for Palestine to become an independent state, which never came to fruition. The Arab Higher Committee expressed their concerns about the White Paper’s vagueness immediately after its publication, arguing that the plan was too vague to be implemented. They also demanded that the government stop transferring Arab-owned lands to incoming Jewish settlers. The 1939 White Paper also limited Jewish immigration to 75,000 over five years and made that immigration contingent on Arab consent. With the simultaneous rise of Adolf Hitler’s murderously antisemitic regime in Germany, the new British policy had the effect of closing one of the few escape routes for Jews seeking to flee Europe on the eve of the Holocaust. |