Why did Britain’s alliances during World War I often work against each other? What made these diplomatic relationships so complex?

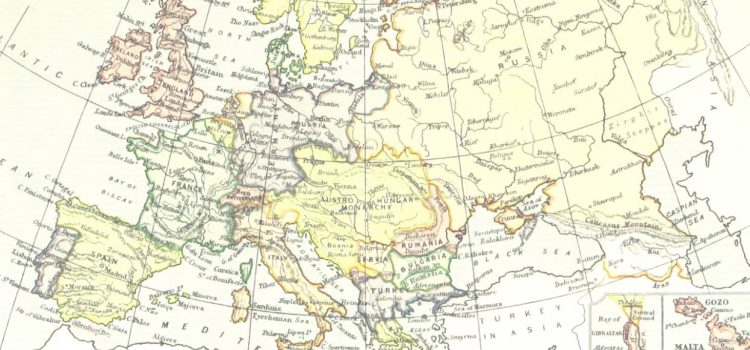

The alliances in World War I created a web of competing interests and conflicting promises. From Russia’s exit from the Triple Entente to Britain’s simultaneous promises to Arab and Zionist leaders, these diplomatic relationships shaped both wartime strategies and post-war outcomes.

Keep reading to get David Fromkin’s perspective from A Peace to End All Peace on how these intricate alliances influenced the course of history.

World War I Alliances

Fromkin discusses the conflicting alliances in World War I. These alliances complicated Britain’s efforts to negotiate with any single group. In addition, Britain struggled to balance immediate goals, such as winning the war quickly, with long-term goals, such as placing British-friendly leaders in strategic places. We’ll describe some of these alliances.

The Triple Entente

Russia’s alliance with Britain and France (“The Triple Entente”) was in peril due to an economic crisis that led to the Soviet revolution. Vladimir Lenin, a Soviet leader who advocated for ending Russia’s involvement in the war, seized control of the Russian government in 1917. Fromkin claims that Britain tried to stall Russia’s exit from the alliance by appealing to the interests of Russian Jews, mistakenly thinking they held a lot of power in the government. Despite Britain’s attempts, Russia signed a peace treaty with Germany in 1918 and left the Entente.

(Shortform note: Britain was not the only one stalling Russia’s defection from the war. After the Czar’s abdication in February 1917, a provisional government ruled Russia. The government included elected representatives of workers and soldiers who gained power through the Revolution and an unelected assembly representing the formerly ruling elite. Although the incoming revolutionaries demanded that Russia leave the war, the elite didn’t agree. It took a second revolution to push the former elite out of the government and place Lenin in power.)

The Anglo-Zionist Alliance

Fromkin argues that Britain’s alliance with Zionism during the war supported both their wartime and postwar goals. Zionism aimed to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine so Jews could self-govern and live free from persecution. The British mistakenly believed that Jews in the US had significant influence and that supporting Zionism would give Britain political and financial backing from the US and Russia. Britain also aimed to control Palestine postwar to block German dominance of key routes to British colonies in Asia and the Pacific, such as India and New Zealand. An alliance with Zionism ensured Palestine remained friendly to British interests.

(Shortform note: The mistaken belief that Jews held decision-making power in Russia and the US is an example of the antisemitic trope that Jews are involved in a global conspiracy. This trope became even more destructive after the war: In 1918, German political and military leaders instigated conspiracy theories about their defeat. Rather than take responsibility, they accused German Jews, among other groups, of conspiring against Germany. This “stab-in-the-back” myth, in addition to the 132 billion gold marks Germany had to pay the Allies as reparation, fueled nationalism and Nazism, leading to the Holocaust.)

Fromkin notes that the Zionist movement arose amid 19th-century European nationalism, which advocated national freedom but fostered intolerance toward minorities. Jews in Western Europe faced hostility and questions about their national identity, while Eastern European Jews endured legal restrictions and violent pogroms (organized massacres of minority groups). These adversities led to calls for an independent Jewish state. Zionist leaders chose Palestine for its religious significance and the existing Jewish communities settling there.

(Shortform note: Some critics of Zionism argue that, alongside nationalism, antisemitism and colonialism were crucial for the Zionist movement. They suggest that Zionists leveraged state-sponsored antisemitism, presenting their project as a “solution” for governments opposed to Jewish communities. These critics point out that British politician Arthur Balfour, who blocked Eastern European Jews from moving to England after persecution, was antisemitic. (He’s best known for the Balfour Declaration, his public statement expressing Britain’s support for Zionism.) Additionally, scholars contend that Zionists sought European colonial powers’ support because relocating a European population to Palestine aligned with imperialist views.)

Anglo-Arab Alliances

Fromkin reveals that the British were intentionally vague in their promises to Arabs and Zionists regarding Palestine, knowing they couldn’t keep their promises to both groups. Also, he says the British government believed Middle Eastern leaders could help end the war more quickly by inciting rebellion within the Ottoman Empire. The British led and financed Arab uprisings to destabilize the region, promising their local agents they’d be able to govern themselves. These revolts helped the British take over key cities across the Arab Ottoman territories.

(Shortform note: Britain capitalized on the cultural disconnect between Turkish and Arab Ottomans to stir unrest within Ottoman society. Before the war, Arab nationalist societies within the Empire convened the First Arab Congress where they demanded more autonomy and the right to use Arabic instead of Turkish as the official language of their local governments. However, some scholars argue that a cohesive Arab identity didn’t fully form until after World War I, making the British-backed Arab revolts more useful to the British than to Arab objectives.)

The Anglo-French Alliance

At the same time, supporting any level of Arab independence challenged France’s regional objectives in Syria-Lebanon, whose Christian communities were under French protection. Fromkin argues that British officials thwarted French objectives in the Middle East. For instance, they supported an Arab leader in Syria despite the French wanting Syria for themselves.

(Shortform note: French objectives in the Middle East included their Syrie Integral project, which involved expanding their influence across all of Greater Syria, including Palestine. While the war kept France preoccupied in Europe, the British sidelined French aspirations in the Middle East.)