This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Rebooting AI" by Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

Is AI really as advanced as we think it is? Are we overestimating its capabilities?

In their book Rebooting AI, Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis explore the gap between AI hype and reality. They discuss how narrow AI differs from the strong AI we often imagine. The authors also explain why we tend to overestimate AI’s abilities.

Keep reading to discover the truth behind AI’s current capabilities and the potential risks of relying too heavily on narrow AI systems.

The Hype About AI

In their book, Marcus and Davis address how public perception of artificial intelligence is skewed. The computer industry, science fiction, and the media have contributed to the AI hype, priming the public to imagine “strong AI”—computer systems that actually think and can do so much faster and more powerfully than humans. Instead, what AI developers have delivered is “narrow AI”—systems trained to do one specific task while having no more awareness of the larger world than a doorknob can understand what a door is for. The authors explain how AI’s capabilities are currently being oversold and why software engineers and the public at large are susceptible to overestimating narrow AI’s capabilities.

(Shortform note: We cover two levels of AI, though some software engineers now divide them into three: narrow, general, and strong. Narrow, or “weak,” AI is trained to perform specific tasks, such as chatbots that mimic human conversation or self-driving systems in cars. General AI will be able to mimic the human mind itself in terms of learning, comprehension, and perhaps even consciousness. Strong, or “super,” AI will be the level of artificial intelligence that exceeds the human mind’s capabilities and can think in ways we can’t even imagine. Some computer scientists, including Marcus and Davis, treat general and strong AI as the same thing.)

AI Fantasy Versus Reality

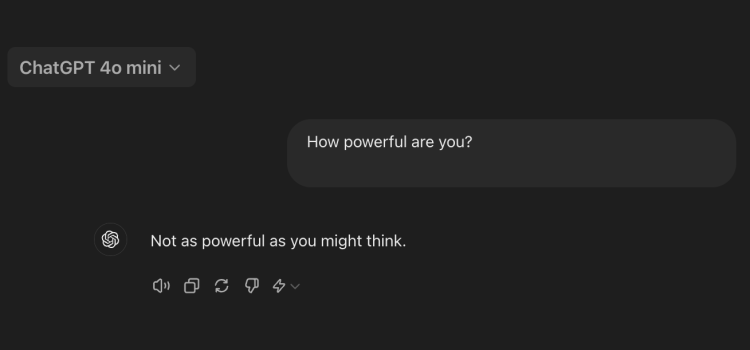

The AI systems making an impact today are far from the benevolent androids or evil computer overlords depicted in science fiction. Instead, Davis and Marcus describe modern AIs as hyper-focused morons who don’t understand that a world exists beyond the tasks they’re trained on. Yet the public’s confusion is understandable—tech companies like to garner attention by billing every incremental step forward as a giant leap for AI, while the press eagerly overhypes AI progress in search of more readers and social media clicks.

(Shortform note: One can generally expect tech companies to paint their progress in a generous light, but contrary to Davis and Marcus’s claims, the news media doesn’t always follow suit. In 2023, when the electric car manufacturer Tesla released a video demonstrating its self-driving AI system, some outlets criticized Tesla’s driving test for its ideal—rather than realistic—road conditions. Earlier that year, The Washington Post reported that Tesla’s AI driver-assist system resulted in more accidents than human drivers without AI support. Thanks to media scrutiny and legal pressure, Tesla recalled more than 2 million cars due to faulty self-driving AI.)

To be fair, technology has made great advances in using big data to drive machine learning. Marcus and Davis take care to point out that we haven’t built machines that understand the data they use and adapt to real-world settings, and the authors list some reasons why this is sometimes hard to see. The first is our tendency to project human qualities on objects that don’t have them—such as claiming that your car gets “cranky” in cold weather, or imagining that your house’s bad plumbing has a vendetta against you. When a computer does things that were once uniquely human, such as answering a question or giving you driving directions, it’s easy to mistake digital abilities for actual thought.

(Shortform note: Our tendency to anthropomorphize objects doesn’t end with computers, or even machines. We do this because our brains are geared to interpret social cues very quickly—therefore, if your mind projects feelings onto an object, you’re better able to easily fit that object into your mental model of the world. This tendency may explain the broad appeal of Marie Kondo’s (The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up) system for organizing your belongings, which involves anthropomorphizing everyday objects. A study on the irrational humanization of computers that Marcus and Davis caution against shows that people do it unconsciously, leading to potentially faulty judgments about whether or not a computer’s outputs should be trusted.)

Shortsightedness in AI Development

The second reason that Davis and Marcus say that modern AI’s abilities are overstated is that developers tend to mistakenly believe that progress on small computing challenges equates to progress toward larger goals. Much of the work on narrow AI has been done in environments with clear rules and boundaries, such as teaching a computer to play chess or a robot to climb a set of stairs. Unfortunately, these situations don’t map onto the real world, where the number of variables and shifting conditions are essentially infinite. No matter how many obstacles you teach a stair-climbing robot to avoid under laboratory conditions, that can never match the infinitude of problems it might stumble upon in an everyday house.

(Shortform note: When AI developers overestimate their progress in the way that Davis and Marcus say they do, this translates into unrealistic expectations from consumers using AI in the real world. For instance, despite warnings about the fallibility of language-generating AI, two New York attorneys used a legal brief written by ChatGPT in an actual federal court. The AI-generated brief referenced several nonexistent court cases, resulting in sanctions against the attorneys, who claimed to have thought that the generative AI was a valid search engine whose responses were accurate. Despite this dramatic failure, some tech advocates are still hyping language-generating AI as a useful tool in legal writing.)

So far, according to Marcus and Davis, AI developers have largely ignored the issue of how to train AI to cope in situations it’s not programmed for, such as setting the stair-climbing robot’s stairs on fire. This is because, for most of its history, artificial intelligence has been used in situations where the cost of failure is usually low, such as recommending books based on your reading history or calculating the best route to work based on current traffic conditions. The authors warn that if we start to use narrow AI in situations where the cost of failure is high, it will put people’s health and safety at risk in ways that no one will be able to predict.

(Shortform note: Marcus and Davis’s predictions for how AI will endanger lives are already coming true, even in a field as seemingly innocuous as using AI to generate text. For instance, the New York Mycological Society has issued a warning to consumers about AI-generated guides to edible mushrooms, some of which may—by way of computer error and lack of human oversight—recommend varieties of mushrooms that are deadly. Amazon’s self-publishing platform, Kindle Direct Publishing, has seen a flood of AI-generated books, many of which are fraudulent attempts to mimic works by established authors and experts, including the aforementioned mushroom foraging guides.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Gary Marcus and Ernest Davis's "Rebooting AI" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Rebooting AI summary:

- That AI proponents oversell what modern AI can accomplish

- How AI in its current form underdelivers on its creators’ promises

- The real danger—and promise—of artificial intelligence