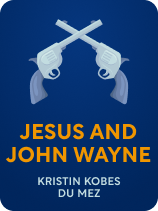

This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Jesus and John Wayne" by Kristin Kobes du Mez. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What’s the complementarian view of scripture? Does it represent “soft patriarchy” in Christianity?

Professor of history and gender studies Kristin Du Mez writes that, in the early and mid-20th century, evangelical Christians shifted toward a militant view of masculinity. Then, a lack of a US military opponent in the ’90s caused this conception to soften.

Continue reading to understand Du Mez’s perspective on “soft patriarchy” within evangelicalism.

Soft Patriarchy in Christianity

Du Mez argues that soft patriarchy in Christianity found its expression in the complementarian view, a pendulum swing away from the militant masculinity promoted by Jerry Falwell Sr. Let’s look at the context.

Du Mez writes that Falwell Sr. was essential to bringing the religious right into the political mainstream. As Du Mez relates, he created the Moral Majority in 1979, an organization that sought to mobilize the religious right in elections throughout the 1980s. In particular, Falwell Sr. promoted a militaristic approach and advocated that America maintain a dominant military to fend off domestic and international threats, largely from Marxists who, according to Falwell, wished to undermine the evangelical family unit.

Du Mez points out that, despite Falwell Sr.’s emphasis on militant masculinity, the US’s lack of a concrete military opponent throughout the 1990s caused this conception of masculinity to atrophy. Instead, evangelicals promoted a less virulent but nonetheless patriarchal view of masculinity according to which men were divinely ordained to lead in the home as servant-hearted leaders—people who lead first and foremost through serving.

According to Du Mez, this shift originated in evangelical theologians John Piper and Wayne Grudem’s 1991 book, Recovering Biblical Manhood and Womanhood. Piper and Grudem defended complementarianism, the view that God considered men and women to be moral equals but assigned them different roles. In particular, they contend that leadership in the house and the church was reserved for men. However, they also argued that men should lead with humility and love, unlike the militant, domineering leadership that Falwell Sr. preferred.

(Shortform note: Even within complementarian circles, evangelicals often disagree about the extent to which leadership in the church and home is reserved for men. For example, some complementarians argue that, although women shouldn’t be senior pastors in the church, they should nonetheless occupy other teaching positions, both at home and in the church. In defense of this view, they point to biblical passages such as Acts 18:26, which praises Priscilla (a woman) for teaching Apollos (a man) inside a synagogue.)

While abstract, Piper and Grudem’s ideas had concrete consequences via the Promise Keepers, an evangelical organization in the late 1990s. Du Mez writes that Promise Keepers promoted the complementarian view of “soft patriarchy” by exhorting evangelical men to become gentle leaders. Promise Keepers members often vowed to become better husbands and fathers by forsaking sinful activities like drinking and adultery and being present in their children’s lives. According to Du Mez, Promise Keepers undermined the militaristic view of masculinity that evangelicals had previously espoused while retaining its patriarchal bent.

(Shortform note: Members of the Promise Keepers organization commit to a set of seven key promises: to honor Jesus Christ; to pursue close friendships with other Christian men; to remain sexually and morally pure; to build strong marriages and families grounded in love; to serve others; to be unified with other Christians; and to influence the world by spreading the message of Jesus’ love.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Kristin Kobes du Mez's "Jesus and John Wayne" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Jesus and John Wayne summary:

- The real reason why Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election

- An analysis of the four historical eras of evangelical masculinity

- The effect that the first and second World Wars had on evangelicals