This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Irrational Exuberance" by Robert J. Shiller. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

What’s the relationship between speculation and the stock market crash? How did the media influence investors?

In both 1929 and 1987, speculation and the stock market crash were deeply intertwined. A look at media coverage at the time shows how speculation set the stage for each crash.

Let’s consider how speculative bubbles influenced by the media led to major stock market crashes in history.

How Speculative Bubbles Set the Stage for Stock Market Crashes

Although feedback loops often set the stage for speculative bubbles, two cultural features sustain and strengthen these bubbles once they take root: media coverage of rising stock prices and economic theories that justify these prices. Both influence speculation and the stock market crash in turn.

How Media Coverage Furthers Speculative Bubbles

When it comes to investing, the media doesn’t just passively present the news. The media actively contributes to investing highs and lows by drawing attention to price changes, which causes further price changes. To show as much, let’s examine media coverage leading up to two key crashes in the US stock market: the 1929 crash and the 1987 crash.

Crash #1: Black Monday and Black Tuesday, October 1929

Black Monday and Black Tuesday refer to Monday October 28 and Tuesday October 29, 1929. During this two-day span, the Dow Jones dropped a total of 23% due to single-day drops of 12.8% and 11.7%—the two largest single-day drops in US history at the time. Normally, we would expect such drops to stem from concrete information impacting companies’ business fundamentals (the information that reflects a company’s financial health, such as its revenue and cash flow). But media outlets reported no such information: The news was replete with mundane stories that had little to do with corporations’ fundamentals.

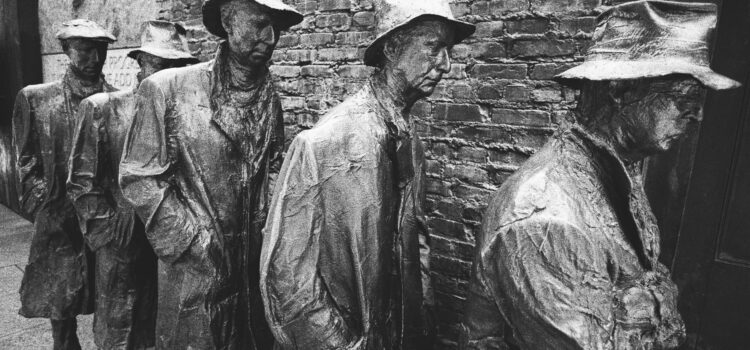

(Shortform note: The calamitous losses on Black Monday and Black Tuesday had wide-reaching implications beyond the stock market—because they depleted investors’ wealth overnight, the US economy tanked instantly. Consequently, these two days ushered in the period known as the Great Depression (1928-1939), in which crippling unemployment and widespread deflation were pervasive in the US.)

However, news outlets did report another story that could have influenced the stock market—namely, the temporary market drop of Black Thursday (October 24, 1929), in which the Dow was down 12% at one point but recovered by the day’s end. On Sunday evening and the morning of Black Monday, prominent news outlets ran stories highlighting the tenuous nature of the market in the wake of Black Thursday. This suggests that Black Monday and Tuesday didn’t result from news about companies’ financial prospects, but rather from increased awareness of market volatility. By making the stock market’s volatility salient, the media caused a chain reaction of price decreases on Black Monday and Tuesday.

(Shortform note: Although this explanation of Black Monday and Tuesday may be correct, it differs from the mainstream economic explanations, which instead cite a proliferation of factors that contributed to the crash. For example, experts note that many investors were purchasing stocks on credit in 1929, meaning that margin calls when the stock market dropped forced them to sell their stocks, causing further losses. Further, the Federal Reserve sharply raised the federal interest rate from 5% to 6% in the weeks before the crash, which may have caused financial markets to be less stable and thus prone to a crash.)

Crash #2: Black Monday, October 1987

In a similar vein, there was the next Black Monday, on October 19, 1987, in which the Dow Jones dropped nearly 23% in a single day—doubling the single-day drops of 1929. Robert Shiller, an economist at Yale at the time, took advantage of this crash by surveying professional and amateur investors the week after the crash to collect their thoughts on the day of the crash. His surveys asked investors to rate the importance of different news stories from October 19 in their assessment of the stock market crash. As Shiller relates, these investors overwhelmingly responded that stories about the Dow’s morning decline—when it dropped around 7%—were the most important for their market evaluation.

(Shortform note: Experts point out that Black Monday in 1987 illustrated the interconnected nature of international financial markets, as the Dow’s crash on October 19 was followed by similar crashes in markets across the world. For example, London’s Financial Times 100 index was down 25% by October 23, and Japan’s stock market was down 13%. Thus, while the US’s stock market lost $500 billion in value on October 19, the total worldwide loss was estimated at over $7 trillion.)

Shiller reasons that although the Dow’s initial fall in the morning may have had something to do with business fundamentals, its subsequent decrease that day was largely driven by news of the initial decrease. He notes that this conclusion was shared by the Reagan administration’s Brady Commission—a group assigned with uncovering the causes of the crash—who found that while initial news reports about unfavorable tax legislation for corporations spurred the initial price drop, further news reports about the price drop itself encouraged further selling, leading to a calamitous crash.

(Shortform note: The Brady Commission’s report also clarified that much of the widespread selling that drove stock prices down on Black Monday was the result of computerized trading: automated programs used by institutional investors that automatically sold stocks under certain conditions. Because these programs were designed to sell stocks that dropped by a certain percentage, they caused initial price drops to give rise to further declines.)

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Robert J. Shiller's "Irrational Exuberance" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Irrational Exuberance summary:

- That financial markets are rife with speculation

- The three key US financial markets where speculative bubbles have formed

- Recommendations to financial leaders and the public for mitigating bubbles