This article is an excerpt from the Shortform book guide to "Grant" by Ron Chernow. Shortform has the world's best summaries and analyses of books you should be reading.

Like this article? Sign up for a free trial here.

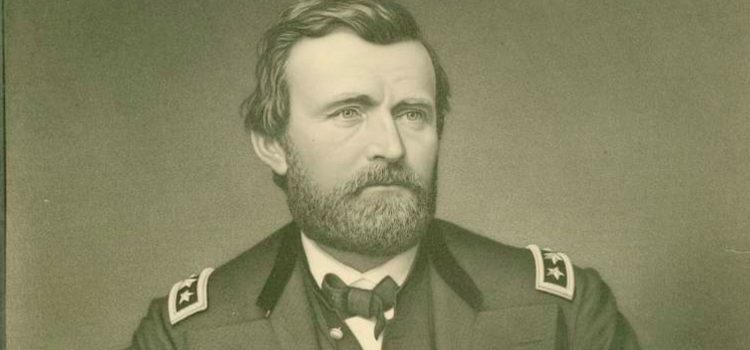

What did Ulysses S. Grant accomplish in the military? How did General Ulysses S. Grant lead the Union to victory?

In Grant, Ron Chernow writes that Grant’s military career spans from the Mexican American-War of the late 1840s to the pinnacle of the Civil War. He focuses on Grant’s military tenure in the Civil War specifically, discussing how Southern secession spurred his return to the service and how he protected ex-slaves.

Learn more about the career of Ulysses S. Grant, general during the Civil War.

Grant’s Opposition to Secession

To understand Ulysses S. Grant, general of the Union Armies, to return to the military—which occurred after drinking allegations led him to resign in 1854—Chernow first examines Grant’s reaction to the news that eleven Southern states had seceded from the Union between late 1860 and 1861, with these states declaring themselves the Confederate States of America and selecting Jefferson Davis as their President. According to Chernow, these secessions galvanized Grant to return to duty, as Grant maintained that secession was unconstitutional and traitorous.

In defense of this claim, Chernow appeals to passages from Grant’s own Memoirs, in which he reflected on the wave of secessions in January of 1861, including Florida, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana. Because the US purchased many of these states through its national treasury, Grant reasoned that they lacked the right to secede. Indeed, Chernow points out that Grant had a visceral response to representatives from Confederate states gathering in February of 1861, who declared themselves the Confederate States of America—interviews with witnesses stated that Grant called for all of the traitors to be hanged.

With his newfound zeal, Grant traveled to towns around Galena, Illinois—his hometown—to seek volunteers to join the military. And although it took some time for Grant to earn an official post, Chernow writes that he became a colonel of the Twenty-First Illinois Regiment in June, officially marking his return to military life.

Grant’s Strategic Savvy During the Civil War

After his return to the military, Grant was promoted to Major General of Volunteers in 1862, making him the second-highest general in the Western Theater (the land between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian mountains). Contrary to Grant’s critics, who allege Grant was closer to a reckless butcher than a savvy leader, Chernow argues that Grant was a cunning strategist and leader in the Civil War, both on and off the battlefield. Though Chernow cites varied evidence to defend this thesis, we’ll focus on two key examples: Grant’s military campaign in Vicksburg and his post-victory treatment of Confederates in Vicksburg and Appomattox.

Grant’s Cunning in the Vicksburg Campaign

Chernow contends that Grant’s crucial victory in Vicksburg, Mississippi, along with the various preceding battles that constitute his “Vicksburg campaign,” showed that Grant was capable of outwitting and outmaneuvering his opponents, propelling him to victory while also losing fewer troops.

For further context, Chernow points out that Vicksburg was strategically vital to the Confederacy as the last Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi River—the key means of distributing goods to Confederate armies. He notes that, as Grant’s 43,000 men marched south toward Vicksburg, they won five battles against a total of 60,000 Confederate soldiers. Yet, while the Confederates suffered 7,200 casualties, Grant suffered only 4,300—a counterpoint to the narrative that Grant rashly sacrificed troops and won battles by overwhelming numbers alone.

Then, after several failed assaults on Vicksburg, Grant instead decided to lay siege to Vicksburg, meaning that he surrounded the fortress to prevent Confederate troops from receiving food, water, or reinforcements. Chernow argues that, because Vicksburg was well-fortified, this was a prudent strategic move; by engaging Vicksburg in a war of attrition, Grant avoided unnecessarily sacrificing troops through continued frontal assaults. Moreover, Grant successfully seized the high ground—Haynes’ Bluff—which left the Confederates with little hope of successfully escaping.

As Chernow relates, Grant’s strategic cunning was rewarded on July 4, 1863, as Confederate General John Pemberton surrendered Vicksburg to the Union; with dwindling rations, the war of attrition left Pemberton no choice but to surrender.

The Magnanimous Victor

According to Chernow, Grant’s strategic genius extended beyond the battlefield. Specifically, Chernow argues that through his magnanimous treatment of defeated Confederate soldiers, Grant displayed a long-term understanding of how to minimize casualties and conciliate the South.

For example, Chernow points out that after the Vicksburg campaign, it was initially tempting for Grant to treat captured Confederates cruelly—as traitors against the Union, harsh retribution seemed a natural response. Yet, he notes that Grant did the opposite: He offered to allow Confederate soldiers to retain traditional war honors and parole them rather than taking them captive. Chernow suggests that, in so doing, Grant practically ensured Confederates accepted his offer of surrender, thus avoiding gratuitous bloodshed.

In a similar vein, Chernow contends that Grant’s treatment of Confederates following their 1865 defeat at Appomattox—in which Grant defeated Southern General Robert E. Lee, marking the beginning of the end of the Civil War—showcased Grant’s understanding of the long-term strategy needed to reunify the nation. Once more, Grant offered Confederate troops parole rather than doling out retributive punishment, even providing food rations for the dilapidated Confederate army. According to Chernow, this magnanimous act won Grant the gratitude of the South and drastically improved the prospects for post-war reconciliation.

Grant’s Consistent Concern for Freedmen

In addition to Grant’s strategic genius, Chernow maintains that Grant also exemplified compassion in his treatment of ex-slaves throughout the Civil War. Specifically, Chernow argues that Grant consistently advocated for the fair treatment of ex-slaves, as shown by his development of “contraband camps” to care for former slaves and his commitment to letting them join the Union army.

First, Chernow points out that in November of 1862, following Congressional orders for Union armies to safeguard former slaves, Grant spearheaded the effort to establish “contraband camps”—encampments in which former slaves were paid for their labor (like harvesting crops and building cabins). Moreover, Grant supplied these freedmen with shelter, food, and clothing to effectively establish their own communities. As Chernow relates, Grant’s initiative even earned him praise from acclaimed Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

Additionally, Chernow relates that in April of 1863, Grant enthusiastically enlisted former slaves into the army as paid soldiers and urged his commanders to do the same, creating the first Black regiments in the Union army. Chernow argues that, in light of the entrenched racism present in the Union army, Grant’s insistence on allowing liberated slaves to join the military was momentous: By encouraging prejudiced Union troops to work alongside these ex-slaves, Grant began to uproot decades of ingrained racism among Northern soldiers.

Chernow contends that both of these actions flowed from Grant’s increasingly firm support for abolitionism. Chernow notes that, in Grant’s 1863 letter to Illinois Representative Elihu Washburne, he expressed an uncompromising conviction that reconciliation with the South could only occur after eradicating slavery, even going so far as to deem the war divine retribution for slavery.

———End of Preview———

Like what you just read? Read the rest of the world's best book summary and analysis of Ron Chernow's "Grant" at Shortform.

Here's what you'll find in our full Grant summary:

- A biography of Ulysses S. Grant that paints him in a new light

- Grant's role in the Civil War and as president of the United States

- How Grant fought valiantly against alcohol addiction